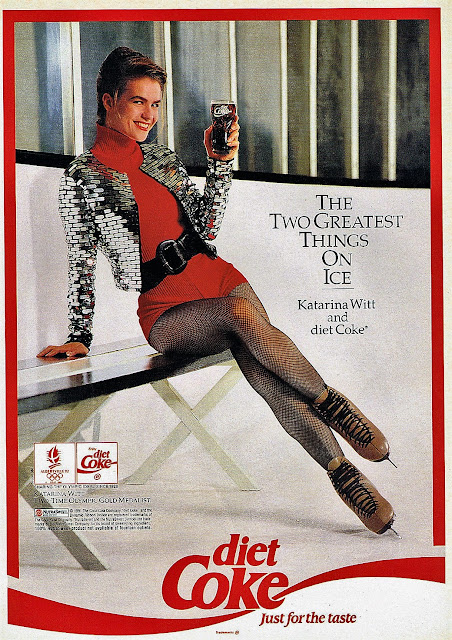

Held at the Riverfront Coliseum in Cincinnati, Ohio from April 3 to 5, 1992, the Diet Coke Skaters' Championships were sponsored by (you guessed it) the good folks at Coca-Cola, along with MasterCard and Reebok. The event was held to mark the five-year anniversary of the 1987 World Championships, held at the same rink and featuring many of the same competitors.

In this particular CBS professional 'made-for-TV' competition, skaters performed three programs (technical, artistic and exhibition) with the technical and artistic programs scored out of 10.0. Unlike other professional events, the high and low marks were not dropped in either program and as in the amateur ranks, the technical program had seven required elements. The winners of both the men's and women's events took home a cool forty thousand dollars.

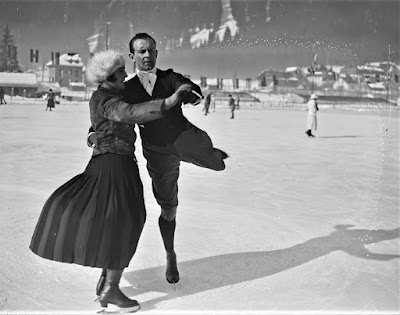

Barbara Underhill, who recently learned she was pregnant, skated a 'guest' exhibition with Paul Martini as there was no pairs event. At the time, the duo believed it may have been their final performance. Underhill wasn't the only pregnant Canadian skater in Cincinnati. Tracey Wainman, who accompanied then-husband Jozef Sabovčík, was extremely close to her due date. Sabovčík worried that she might end giving birth to their son Blade in Cincinnati.

Barbara Underhill, who recently learned she was pregnant, skated a 'guest' exhibition with Paul Martini as there was no pairs event. At the time, the duo believed it may have been their final performance. Underhill wasn't the only pregnant Canadian skater in Cincinnati. Tracey Wainman, who accompanied then-husband Jozef Sabovčík, was extremely close to her due date. Sabovčík worried that she might end giving birth to their son Blade in Cincinnati.

The Diet Coke Skaters' Championships was to have been part of a planned four-part professional series organized by Jefferson-Pilot Communications called The Skater's Championships. The first event was Les Dieux de la Glace - Masters Professionels de Patinage (the first Miko Masters) held in June of 1991 in Paris. The second was the International Figure Skating Championships in Atlanta in December of 1991. The Cincinnati event ultimately ended up being the third and final stop.

The task of promoting the event fell on the lap of Don Schumacher, the executive director of the Greater Cincinnati Sports and Events Commission. Whatever Schumacher did worked. Tickets for the three-day event, which ranged from twenty-five to thirty-five dollars per day, sold like hot cakes, with visitors from as far away as Canada flocking to the Queen City to see their favourite skaters compete. Join me in the time machine as we look back at how this overlooked event played out!

THE MEN'S COMPETITION

Making his professional debut after winning the 1992 Winter Olympic Games and World Championships, Viktor Petrenko nailed a triple Axel on his way to winning the men's technical program ahead of Brian Orser, Jozef Sabovčík and five others.

Gary Beacom, skating first in the artistic program, performed a self-choreographed avant garde program to Patrick O'Hearn's "Malevolent Landscape" clad head to toe (literally... his entire head was covered) in a black spandex bodysuit. The judges weren't amused. World Champion Alexandr Fadeev was next to skate, and he received marks that were even lower. Robin Cousins, sixth after the technical program, had the audience spellbound with his self-choreographed interpretation of k.d. lang's "Busy Being Blue". Though his program didn't include a triple jump, it did include a double Axel and his signature layout backflip. He was the only skater other than the winner to receive a perfect 10.0. Scott Hamilton, who'd faltered in his technical program and placed only fifth, rebounded with a flawless performance choreographed by Ricky Harris to a choral version of "The Battle Hymn Of The Republic". The program was dedicated to the victims of the 1961 Sabena Crash. He received 10.0's across the board and catapulted into first place. Brian Orser followed with a subdued performance to Michael Feinstein's "Where Do You Start?", doubling his only planned triple attempt and earning marks from 9.7 to 9.9. Petrenko finished well outside of the top three in the artistic program when he made the decision to perform his Olympic free skate as an artistic program, despite being advised against it by both judges and his fellow competitors. Though he was the only skater to attempt and land a triple Axel, he missed three other jumping passes. Even the commentators on CBS pondered why he hadn't chosen to perform the number he used in the Exhibition Of Champions - Chubby Checker's "Let's Twist Again" - instead. Robert Wagenhoffer and Jozef Sabovčík followed, each failing to earn marks that placed them in the top three. Hamilton took the win and Petrenko's strong technical program lead kept him in second, ahead of Orser, Cousins, Sabovčík, Wagenhoffer, Beacom and Fadeev.

THE WOMEN'S COMPETITION

Scott Hamilton, who left Verne Lundquist and Tracy Wilson to their own devices in the CBS booth during the broadcast of the men's event, offered his commentary for the women's event. Katarina Witt won the technical program with one of the most technically demanding performances of her entire professional career, skating to an early version of the "Robin Hood" program she would later use when she reinstated to the amateur ranks for the 1993/1994 season. Debi Thomas and Liz Manley, Witt's fellow medallists from the 1988 Winter Olympics, followed in second in third place. A pair of World Champions, Denise Biellmann and Rosalynn Sumners, were tied for fourth ahead of Charlene Wong and Caryn Kadavy.

Caryn Kadavy, first to skate in the artistic program, choreographed her own program to "Nessun Dorma" from "Turandot" but missed all three of her jumping passes and only managed to earn 9.5's and 9.6's. Biellmann followed, uncharacteristically missing both of her jumping passes as well. She earned marks ranging from 9.4 to 9.8. The audience came around when Rosalynn Sumners skated a clean performance to Roberta Flack's "The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face", replete with four double jumps. Her marks, ranging from 9.7 to 9.9, easily broke her earlier tie with Biellmann. Charlene Wong's artistic program left her sandwiched between Sumners and Biellmann and Kadavy.

THE MEN'S COMPETITION

Making his professional debut after winning the 1992 Winter Olympic Games and World Championships, Viktor Petrenko nailed a triple Axel on his way to winning the men's technical program ahead of Brian Orser, Jozef Sabovčík and five others.

THE WOMEN'S COMPETITION

Scott Hamilton, who left Verne Lundquist and Tracy Wilson to their own devices in the CBS booth during the broadcast of the men's event, offered his commentary for the women's event. Katarina Witt won the technical program with one of the most technically demanding performances of her entire professional career, skating to an early version of the "Robin Hood" program she would later use when she reinstated to the amateur ranks for the 1993/1994 season. Debi Thomas and Liz Manley, Witt's fellow medallists from the 1988 Winter Olympics, followed in second in third place. A pair of World Champions, Denise Biellmann and Rosalynn Sumners, were tied for fourth ahead of Charlene Wong and Caryn Kadavy.

The top three women after the short program retained their positions in the artistic program, with Manley earning one 10.0, Thomas three 10.0's and Witt perfect 10.0's across the board. Manley, skating to Bette Midler's "Miss Otis Regrets", delivered the most energetic of the three performances. Witt was the only one to land a triple jump, but of the three she received the most tepid response from the audience. Spending most of her program to Louis Armstrong's "Let's Fall In Love" vamping it up and standing and posing, even Scott Hamilton remarked, "I think they were expecting to see a lot more skating and a lot less posing." Debi Thomas, skating an uncharacteristically classical program to "Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini", was quietly radiant but two-footed the landing of her only attempted triple. She still received a standing ovation from the audience, who booed her lower scores. It would prove to be her final professional competition until she made a comeback in the fall of 1996 to compete in two events after having her son.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.