Photo courtesy Toronto Public Library, from Toronto Star Photographic Archive. Reproduced for educational purposes under license permission.

"Figure skating has given me an opportunity for over 50 years to work as a volunteer involved with our young and older skaters, and to be at the center of building programs that have led to the evolution of Canadian figure skating." - Suzanne Morrow-Francis, "The Legendary Night Of Figure Skating" program, 1999

Photo courtesy "Canadian Skater" magazine

Wallace 'Wally' William Distelmeyer was born July 14, 1926, in Kitchener; his partner Suzanne 'Suzy' Morrow on December 14, 1930, in Toronto. He was of German ancestry and born in a Lutheran household; she had Irish roots and her family attended the United Church. He started skating at the age of ten, encouraged by a neighbour. She took up the sport at the age of nine at a doctor's suggestion, to strengthen an injured leg.

Wally made his debut at the Canadian Figure Skating Championships in 1941, finishing second in the junior pairs competition with partner Floraine Ducharme. The following year, the promising young duo won the junior pairs competition and 'skated up', placing second in the senior pairs event. Floraine and Wally's partnership dissolved when he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy during World War II. Suzanne made her first big splash at the 1945 Canadian Championships, following in Wally's footsteps and winning the junior pairs event and finishing second in the Waltz... with Frances Dafoe's future partner Norris Bowden.

Suzanne Morrow. Photos courtesy Hamilton Public Library (left) and "Skating World" magazine (right).

By the following year, Suzanne and Wally decided they made better partners than competitors. He finished second in the senior men's event at the 1947 Canadian Championships; her third in the senior women's behind training mates Marilyn Ruth Take and Nadine Phillips. Together, they won the senior pairs title on their first try, defeating a talented Winnipeg brother/sister team, Sheila and Ross Smith. They both made their international debuts at the 1947 North American Championships in Ottawa. She finished fourth in the women's competition; he third in the men's event, sandwiched between Americans Dick Button and Jimmy Grogan and Canadian teammate Norris Bowden. They won the pairs competition, defeating Yvonne Sherman and Robert Swenning, Karol and Peter Kennedy and the Smith siblings. Despite the fact they were a brand new team, their impressive win in Ottawa suggested to many that they had as good a chance as anyone at a medal the following year at the Winter Olympic Games in St. Moritz.

Left: Suzanne and Yvonne Sherman. Photo courtesy "Skating" magazine. Right: Suzanne tying her skates.

Suzanne and Wally's Aussie coaches even helped add a new trick to their arsenal: a one-handed variation of the two-handed death spiral which was a popular 'trick' among professional pairs skaters in the twenties and thirties, first popularized in the amateur ranks by Swiss pair Pierrette and Paul Du Bois.

The pair toiled away on their secret weapon, eventually perfecting it to a degree that Suzanne reached a low, arched-back position while Wally pivoted her around him. They have been widely credited as the first team to perform this version of the death spiral in amateur competition, though Emília Rotter and László Szollás performed it before World War II and Joyce and Colin Bosley and Gladys Hogg and Edwin Edmonds performed it in the I.P.S.A. Professional Championships in England in 1946. If you're big on 'firsts', it can safely be said they were the first North American pair to master the death spiral and perform it at the Olympics and World Championships.

At the 1948 Canadian Championships in Toronto, Wally won the senior men's event and Suzanne finished last in the senior women's event. Together, they claimed first in no less than four events: the senior pairs competition, Silver Dance, Waltz and Tenstep. At seventeen and twenty-one, they had both earned spots on the Canadian Olympic Team.

Suzanne signing the City Of Montreal's guestbook. Photo courtesy Archives of the City of Montreal.

Both Suzanne and Wally had dismal finishes in the singles event in St. Moritz - twelfth and fifteenth - but together, they gave what many considered the performance of the night in the pairs competition. In the middle of a blinding snowstorm, the Ontario duo put on a brilliant show - side-by-side double jumps, speed galore, death spiral and all - but were placed a disappointing third behind Belgians Micheline Lannoy and Pierre Baugniet and Hungarians Andrea Kékesy and Ede Király. The official story was that they were penalized for starting their program with an illegal lift, but there were grumblings that the Belgian and Austrian judges had done some wheeling and dealing.

Dick Button, Suzanne and Hellmut Seibt. Photo courtesy Bildarchiv Austria.

Barbara Ann Scott, Marilyn Ruth Take and Suzanne Morrow at the 1948 Winter Olympic Games

If losing at the Olympics in St. Moritz was a disappointment, Suzanne and Wally's experiences at the World Championships that followed in Davis added insult to injury. After placing ninth and an unlucky thirteenth in the singles events, Suzanne and Wally again skated their program in a dreadful snowstorm - this time after midnight - but performed so well that they were called back on the ice for another bow after finishing their program. The conditions were so poor that as soon as they were done, nearly a dozen snow-scrapers set to work clearing the ice. As insurance against funny business from the judges, the father of the American pair Karol and Peter Kennedy brought his camera along to photograph the performances of the top pairs. He allegedly took a photograph of Lannoy and Baugniet falling, and according to Beverley Smith's fantastic book "Talking Figure Skating", his "camera disappeared from the room and was returned later, but with the film removed." Though they again skated the performance of the evening, Suzanne and Wally were again placed a decisive third, with ordinals ranging from second to fifth place.

Following their Olympic and World medal wins, Suzanne and Wally gave exhibitions in Paris, London, Bournemouth, Edmonton, Vancouver, Winnipeg, Ottawa and St. Catharines. Wally decided to retire from competition; Suzanne pressed on, determined to make a go of it as a singles skater.

Photo courtesy Joseph Butchko Collection, an acquisition of the Skate Guard Archive

As a soloist, Suzanne never quite was able to fill the shoes of Barbara Ann Scott, but it wasn't for a lack of trying. Studying under Gustave Lussi, she greatly improved both her school figures and jump technique and won three Canadian senior women's titles, the silver medal at the 1951 North American Championships in Calgary and finished in the top six at four consecutive World Championships and the 1952 Winter Olympic Games in Oslo. At the 1950 World Championships in London, England, one judge was so impressed by the fact that the fact she did three double loops in a row that he had her in first place in free skating. Incredible accomplishments all, considering that her career was almost sidelined by an automobile accident down in the States that was so serious she required stitches to her face.

Photo courtesy "Skating" magazine

Despite the fact she never won a medal at the World Championships as a singles skater, Suzanne remains to this day the only woman in post-War figure skating history to hold Canadian senior titles in singles, pairs and ice dance. By all accounts, she was also a very talented skier.

Photo courtesy "Canadian Skater" magazine

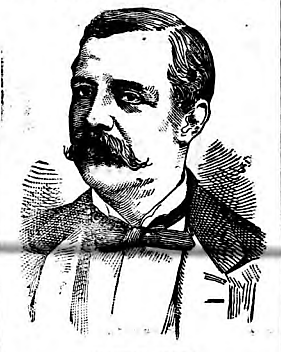

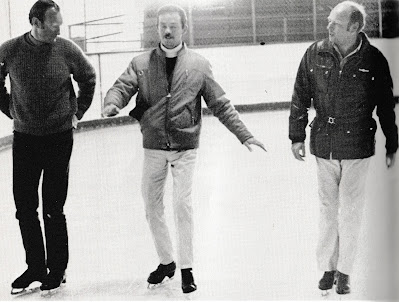

Bob McAvoy, Mary Petrie McGilllvray and Wally Distelmeyer in 1969. Photo courtesy Marie Petrie McGillvray.

Wally also served on the board of the Figure Skating Coaches Of Canada, was a member of the Ontario Sports Council and was on the committee for the CFSA's Bursary Fund. He married Bette Wrinch, the 1947 Canadian Champion in junior pairs, and had two children and four grandchildren. He skated until he was seventy-one, and was a passionate collector of figure skating memorabilia, including sixty pairs of antique skates dating back to the nineteenth century. In an interview with Lois Carson in the Spring-Summer 1979 issue of the "Canadian Skater" magazine, he likened his fascination with skating history to a "disease" that he hadn't "been able to get out of [his] system." Very sadly, Wally passed away on December 23, 1999, in Oakville, Ontario from two far crueler diseases - Parkinson's and Alzheimer's - at the age of seventy-three.

Suzanne excelled in so many different fields during her post-skating life that it is hard to even keep track of it all. After graduating from the Ontario Veterinary College at the University of Guelph and earning her doctorate, she became the proprietor of the Sainte Claire Veterinary Hospital. She divided her time between her veterinary practice and flipping heritage farmhouses in the area north of Toronto. Her first husband, James Pogue, was a professional horse trainer. She met her second husband, David Worthington Francis, while attending college. For several years, she ran a thoroughbred horse racing stable and showed horses internationally. In 1967, her horse won the prestigious Rothman Puissance Jumping Stake. She was also a German Shepherd and Doberman Pinscher breeder, a show judge for the Canadian Kennel Club and the first female veterinarian in Canada to receive a license to practice at race tracks. Her love of animals extended back to when she was competing when she bred blue Persian cats.

Hayes Alan Jenkins and Suzanne Morrow

Suzanne was also a mother and an extremely accomplished international judge. Her first of four trips to the Winter Olympic Games as an official was a bit of a bust. The pro-German crowd at the 1964 Olympics in Austria already had a major hate on for her because she was a low marker. When she placed Marika Kilius and Hans-Jürgen Bäumler behind the Protopopovs and Debbi Wilkes and Guy Revell, they went certifiably berserk... and Kilius was furious. The European press dubbed her 'The Red Devil Of Innsbruck' because she wore a bright red coat while she judged. Things got so bad she was getting harassed when she walked down the streets, spat on and shoved. In one effort to avoid the angry throngs, she sent Marg Hyland out in her famous scarlet jacket as a decoy.

'The Red Devil Of Innsbruck' served her first of two ISU suspensions in 1967 when she rated an American skater over Austria's Emmerich Danzer and gave higher marks than any other judge to Canadian Donald Knight. Her second suspension was served up after the 1976 Winter Olympic Games (again in Innsbruck) where she placed Toller Cranston ahead of John Curry in the free skating. She defended her judging to the 'powers that be' on both occasions. She called things as she saw them and wasn't afraid to go against the grain, even if her opinions were unpopular with some. She defended herself as a judge in an interview in the March 7, 1978 issue of "The Ottawa Citizen" thusly: "I'm not sure it's national bias. We're used to seeing a certain style of skating because we live with it and appreciate it more than styles unfamiliar to us. Some judges are purists - purely technical. Others lean to artistic performance. In most cases, the champion is the right person. One judge out of line doesn't make much difference. The opinion should be accepted without fear of ostracism... You must judge what you see that day."

After judging at the 1980 Olympic Games and several other major international competitions, Suzanne became the first woman in history to give the Judge's Oath in the Opening Ceremonies of the Winter Olympics at the Calgary Games in 1988, where she judged the pairs event. Later that same year she was inducted into the Canadian Amateur Sports Hall Of Fame alongside fellow Olympic Medallist Brian Orser.

Suzanne put away her clipboard and pencil in the summer of 1993, disillusioned after a referee wrote what she felt was an unfair report about her judging of the dance event at the 1992 Skate Canada competition in Victoria, British Columbia. She went on to survive breast cancer and quadruple bypass surgery before suffering a stroke in 2005 and passing away from respiratory and heart problems in Brantford, Ontario at the age of seventy-five on June 11, 2006. Debbi Wilkes recalled, "Suzy was a wonderful girl... just wonderful. Very clever woman. She was a great ambassador and so knowledgeable and confident in her judging skills. Because she had been a top-notch pair skater herself, she really knew what quality was. Not trickery, but real skating quality, and rewarded it appropriately. She was very generous in explaining to me what she felt true quality was... To have that kind of insight and be able to understand from a judge's perspective, 'Here's what we're looking for', was amazing. I think I had some sort of response one time like, 'Well, you don't understand what we're doing.' She said, 'It's your job to make me understand!' Such a piece of wonderful wisdom."

Suzanne and Wally were inducted into the CFSA (Skate Canada) Hall Of Fame in 1992 and were featured on a Canada Post souvenir envelope in 1998. However different their journeys might have been, I think you would be hard-pressed to find many other people who exemplified lifelong devotion to the sport more than these two shining stars from skating history past.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.

.pdf.jpg)