President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had just established the March Of Dimes to combat infant polio, Thornton Wilder's famous play "Our Town" made its debut only weeks earlier and everyone was tapping their toes to Benny Goodman's steppy new tune "Sing, Sing, Sing".

The Ardmore Rink

Pictorial courtesy "Skating" magazine.

Hosted by the Philadelphia Skating Club and Humane Society, the competition marked a 'grand opening' of sorts for the newly constructed, member-owned Ardmore rink, which cost an estimated one hundred and forty four thousand dollars to build. It had only opened on January 8 of that year, so skaters could still smell the paint from the navy-blue ice when they arrived to compete.

THE NOVICE AND JUNIOR COMPETITIONS

To the delight of the hometown crowd, Arthur 'Buddy' Vaughn Jr. of the Philadelphia Skating Club and Humane Society managed to hold on to an early lead in the school figures and win the novice men's crown. However, the performance of the night came from Bobby Specht, who moved up from fifth to take the silver with an outstanding free skating performance. Floyd 'Skippy' Baxter settled for the bronze ahead of William Grimditch, Jr. and achieved fame the next year by becoming the first man to perform the Axel jump on clamp-on roller skates. Twelve year old Gretchen Merrill, representing the Skating Club of Boston, emerged victorious in a field of twenty novice women. Charlotte Walther of New York bested Dorothy Snell and Mary Taylor in the junior women's event.

Gretchen Merrill

THE MEN'S COMPETITION

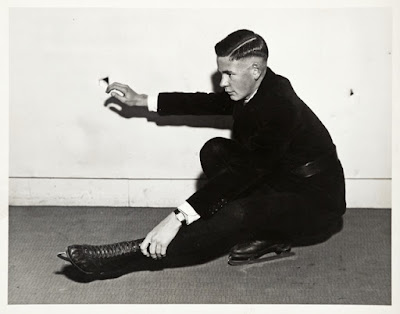

Robin Lee

seventy five points and Manhattan's William Nagle far behind with three hundred and ninety three.

Erle Reiter. Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society.

By accounts, all three of the top men delivered fine performances in the free skating, but the standings didn't change. Lee won his fourth consecutive U.S. men's title and American Railway Company agent William Nagle claimed yet another a last place finish. Former USFSA President and ISU historian Benjamin T. Wright recalled of Nagle, "He just kept entering and entering... and he always finished last!" The only exception to 'the Nagle rule' was at the 1930 U.S. Championships, when the man somehow managed to win the junior pairs title with Helen Herbst.

THE WOMEN'S COMPETITION

After Maribel Vinson turned professional, the U.S. women's title was up for grabs and there were five talented women chomping at the bit to stake their claim to it. Five foot five, sixteen year old Joan Tozzer, the only child of a Harvard Professor of Anthropology, took a strong lead in the senior women's school figures over nineteen year old Audrey Peppe, the niece of Olympic Medallist Beatrix Loughran, Katherine Durbrow of New York, Polly Blodgett of Boston and Jane Vaughn of Philadelphia. Vaughn had the unfortunate luck of taking a rare fall in the figures, placing her further behind than she likely would have been otherwise. However, the "Philadelphia Inquirer" noted that Vaughn's "four-minute free skating exhibition surpassed that given by the Misses Tozzer and Peppe."

Sadly, Jane Vaughn's mishap in the figures placed her so far behind she was only able to move up to fourth ahead of Durbrow, with Tozzer, Peppe and Blodgett taking the top three spots. Tozzer's victory over Peppe was actually extremely close - one tenth of a point close - and Peppe's free skate to "Hungarian Rhapsody" earned her more points than Tozzer in that phase of the event. Tozzer told a "Philadelphia Inquirer" reporter, "Winning the title was quite a shock. Of course I was surprised and am thrilled and everything." She had been skating for six years under the tutelage of Willie Frick and her victory was remarkable in that some years prior she was thrown from a horse and trampled, suffering a broken leg. The February 27, 1938 issue of "The Philadelphia Enquirer" noted that Jane Vaughn "finished fourth, but her four-minute free skating exhibition surpassed that given by the Misses Tozzer and Peppe." Complaints over Peppe's loss to Tozzer continued at the Skating Club Of New York long after the event, but (as is always the case) nothing came of it.

Joan Tozzer and M. Bernard Fox

Later the same night that she won her first U.S. women's title, Joan Tozzer teamed up with twenty one year old Harvard senior M. Bernard Fox to win her first U.S. pairs title. Another Boston pair, Grace and Jimmie Madden took the silver, while Ardelle Kloss Sanderson and Roland Janson of New York took the bronze. Tozzer and Fox's win was a considerable upset at the time, as the Madden siblings were considered by many to be the logical successors to the crown vacated by Maribel Vinson and Geddy Hill.

A fours competition was not contested that year. A whopping fourteen teams entered the Silver Dance competition, a testament to the popularity of ice dance in the U.S. during the pre-War and War eras. After an elimination round, Nettie C. Prantel and Harold Hartshorne took top honours, ahead of Katherine Durbrow and USFSA President Joseph K. Savage, Louise Weigel and Otto Dallmyer and Marjorie Parker and George Boltres. All four of the finalists represented the Skating Club of New York.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.