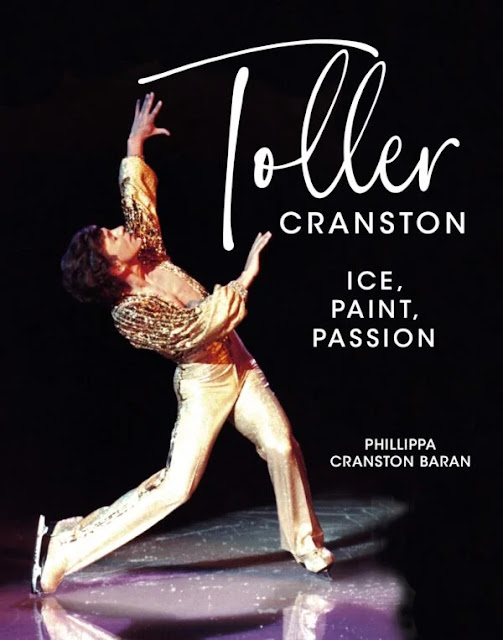

It is not often that a book comes along that absolutely floors you - but I can promise you that the new book "Toller Cranston: Ice, Paint & Passion" will do just that.

This wonderfully important book is a step into the Wonderland of Toller's art and a celebration of his life, full of dozens of unexpected stories that will make you laugh and cry. I was absolutely delighted to contribute to this book, alongside a who's who of Canadian figure skating, including Kurt Browning, Brian Orser, Tracy Wilson, Donald Jackson, Sandra Bezic, Debbi Wilkes, Elladj Baldé, Beverley Smith and PJ Kwong.

Today I'm talking Toller with the author of the book, Toller's sister Phillippa Cranston Baran!

Phillippa Baran Cranston

Q: When and how did the idea for the book came about and how did it evolve during the writing process?

A: Toller suffered a catastrophic heart attack in Mexico on January 23, 2015. In those early days, I didn’t know how or what form preserving his legacy would take, but I knew that the task had fallen to me. A book was an obvious choice. I knew that I could write about Toller as a little boy, and I could write about what it took to clear an estate property in Mexico of 18,000 things in 45 days, but I definitely could not write about figure skating judging, or about the influences and themes in his paintings, or about his impact on people - gay, straight, famous, not famous. I didn’t try. What I did was reach out to individuals with the authority and experience to comment or explain. In the process of creating this book, more than 150 people have contributed deeply personal, incredibly moving, and utterly authentic stories. There are icons like Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen, champions like Don Jackson and Brian Orser, and others who are not so well-known, including skating fans and Toller’s Mexican staff. Collectively, the stories and pictures create a tapestry of the richness, depth, and impact of Toller’s life.

In this book, I set out to present Toller Cranston from a variety of perspectives. I tried to get the hard facts right. I tried to capture the authenticity and the spirit of my brother. The sparkle. The flamboyance. All of it. I have thought many times that had Toller lived another 20 years, which might have been expected since he was only 65, I would be long gone. And so too would a cohort of friends, competitors, collectors, and admirers from all over the world. Who would be left to tell the story? Like in the musical Hamilton, “Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?”

Q: What was it like growing up with Toller?

A: What was it like growing up with Toller? is exactly the question that begins Chapter 2. The first word that comes to mind, is “ordinary” although there was never any doubt that Toller was special. As a child he believed that he was not actually born of parents but was found under a cabbage leaf by the faeries. Maybe he was. Who can be sure? Certainly, there are elements of magic in his life story. There is also a lot of middle-class normalcy. Do your chores, make your bed, feed the dog, finish your homework. No, you do not get rewarded for a decent report card, that is your job. There is also hard work, training, discipline, and an intense drive to create. Chapter 2 describes some of the early influences - his imaginary friend Glunk Glunk, the Raptors and the Rats, the shows, summers at the cottage, discovering figure skating, and the impact of flowers, words, nature, legends, and magical creatures.

Toller Cranston

Q: What do you take away from how Toller was treated by the skating establishment at the time he was competing?

A: Back in the day, everyone who watched figure skating knew that Toller Cranston was “cheated” by the judges. We knew it because we saw it with our own eyes. Was it bias, politics, fear of the unusual, or snobbery on the part of the skating establishment? I don’t know. I still don’t know.

Toller has said many times that when he didn’t get the recognition from the judges, he had to work harder. He had to prove himself again and again and again. In many ways, that need to constantly prove himself fueled his career. Maybe it’s the old cliché that “if it doesn’t kill you, it makes you strong." Regardless, Toller became incredibly strong. He stayed true to his vision of what skating could be and he worked like a demon to be creative with everything he did.

When I was doing research for this book, I tried to gain some understanding of what on earth was going on with the judges all those years ago, and what were they thinking, and did they now, after 40 or 50 years, acknowledge any unfairness? What judge Dorothy Leamen said to me was eye-opening. She said, and I quote, “I remember a competition at Maple Leaf Gardens, when I had just judged the senior men. After the event, Toller stopped me and started ranting and screaming, 'You don’t understand me! You never give me anything!' At the time, I confess I didn’t like a lot of things he was doing especially with the music. When he was finished, I said, 'Toller! It is your duty to make me understand!'”

Toller obviously took that to heart. He accepted that it was his duty to make people understand and he met that challenge every single day of his life. Half a century later, his influence is still felt, his courage is still admired, his creativity is still acknowledged and respected.

Left: Toller Cranston. Photo courtesy "Toronto Life" magazine. Right: John Curry.

Q: Though their styles of skating were completely different, Toller and John Curry are often compared because they made such significant artistic impacts on figure skating at the same time. What are your thoughts on their intersecting roles in skating history?

A: I’m not actually sure that it was ever about a difference in style. It was about a difference in luck, timing, courage, and integrity. All the talk about stylistic difference - the balletic versus the theatrical, is specious. Both Toller and John Curry were expressive, interpretive, and talented. Both were outstanding skaters. Both were committed and passionate about their sport. But here is the truth.1

There is no question that for Toller, not having won an Olympic gold medal in 1976 ate away at him for years. Toller and his lifelong friend Haig Oundjian, former British Champion, often spoke about how John Curry, Toller’s archrival, had seemingly come out of nowhere and snatched Olympic glory. John Curry was well behind Toller in the days of the old judging system. When a skater was behind, they stayed behind. Going into the Olympics, Toller had every reason to expect that he would remain ahead of the British skater. But then this happened - Italian-born coach Carlo Fassi was looking to bring a male skater to Colorado Springs, where he coached. In 1974, Fassi, who was a very political creature, called Toller and said: “Toller, I have Dorothy Hamill here. I have all the facilities, and I want you to come to Colorado and train with me and my wife and we will make you an Olympic Gold Medallist.” They offered free lessons, free ice, even a car. Toller said, “Does that mean I have to leave Ellen Burka?” “Yes,” Fassi said. “You do. The offer is open right now. There’s a ticket booked with your name on it. Come down.” Toller said “No. I can’t do that. Mrs. Burka has been a wonderful coach and a wonderful friend. She’s given me great guidance and it’s my feeling that between the two of us, I have as good a shot at the gold medal as anyone else.”

Fassi was on the phone an hour later to Curry, offering him the same thing - an Olympic gold medal. Within a day, John Curry was on a plane and Alison Smith, his coach was dropped.

John Curry’s life was difficult after his Olympic gold and according to his biographer, he died penniless in 1994. Toller’s career flourished.

Along the way, Haig tried many times to convince Toller that becoming an Olympian is exceedingly difficult. Toller called Haig one morning in January, 2015 shortly before he died, and said, “Haig, I’ve had an epiphany.” “Another one?” said Haig. “Yes,” Toller said. “Do you know who I am?” “No,” Haig said. “Why don’t you tell me?” Toller said: “I’m an Olympian.”

1 With thanks to "Tea for Toller" by Beverley Smith and "Alone", the 2014 biography of John Curry by Bill Jones.

Andre Araiz's stunning video of Toller Cranston's home and gardens

Q: How did you balance writing about Toller the skater, Toller the artist and Toller the person?

A: Toller’s tombstone in the gringo section of the cemetery in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico kind of says it all. It is inscribed simply, Toller, Artist, 1949-2015, Zero Tollerance. He was an artist on ice, in the studio, in his life, and in the creation of his property in Mexico. He had zero tolerance for stupidity, rigidity, mediocrity, incompetence, or half-assed effort. He had zero tolerance for giving less than one’s all. This book looks at all aspects of Toller’s life and it unfolds through the voices of those who knew him, competed with him, and were inspired by him.

Phillippa Baran Cranston

Q: What's your own favourite Toller story?

A: I would say that my own favourite Toller story is the last story I heard from the last person I talked to. Everyone has a Toller story. Whether they ever met him or not. Knew him or not. Saw him skate or not. Owned a painting or not. Everyone has a story. I write in the book that on the day that he died, it seemed that everyone in San Miguel de Allende was with him. I had lunch with him. I met him for breakfast. I went shopping with him. I met him for dinner. I went to his house. He came to my house. I saw him on the street. I spoke to him at the bank. It isn’t true of course but what is true is that everyone felt a deep personal connection. This book contains a lot of stories, a lot of memories, feelings, and emotion. I hope readers will connect with the various perspectives and see themselves reflected back.

Q: What do you think readers will find most surprising about the book?

A: Everything. His humanity, his vulnerability, his capacity to create, his ordinariness. The depth and range of his achievements is astounding. Toller was funny, humble, curious, arrogant, disciplined, outrageous, and, as the last chapter says Quite Simply Human.

One thing readers will not be surprised to learn from Toller is that Leonardo de Vinci was never the figure skating champion of Italy and Michaelangelo, genius that he was, could not execute a double Axel.

Toller Cranston sharing a laugh with Rosalynn Sumners, Katarina Witt and Brian Boitano

Q: One of the aspects of the book that I just love is how it incorporates how Toller's story intersected with so many remarkable Canadians - people like Joni Mitchell, Margaret Atwood, Leonard Cohen and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Why is this book relevant to all Canadians?

A: I am incredibly proud (and frankly astounded) at the impact Toller has had on other people: artists, athletes, performers, fans, and his Mexican staff. There is a chapter in the book called The Muse that describes works of art in many different fields - painting, theatre, poetry, music, ceramic, skating of course, even needlepoint - all either inspired by Toller or made as a tribute to him. That is amazing to me. But I think what I am most proud of is his legacy as a human being - his courage, work ethic, and creativity. That is the legacy he leaves for all of us. Inspiring people to dream big, do the work, live without fear, and be creative now.

Writing this book was a challenge. Horrible, scary, awful, uncertain sometimes, but satisfying. What kept me on track was being committed to the goal and being clear about the end result. That, and the love and support of people who cared. I wouldn’t change a thing.

Toller Cranston in "Strawberry Ice"

"Toller Cranston: Ice, Paint, Passion" will be published on March 5. Readers are invited to attend public launch events at The Donna Child Fine Art Gallery in Toronto, ON, O'Brien Theatre in Arnprior, ON and Hotel Aldea - Ancha de San Antonio in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

You can pre-order your copy today directly through Sutherland House Books or on Amazon, Barnes & Noble or Chapters. Stay tuned to the blog for a review of the book!

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "Jackson Haines: The Skating King", "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://www.skateguardblog.com/p/buy-book.html.