Explore

The Eleventh Annual Skate Guard Hallowe'en Spooktacular

The 1975 Skate Canada International Competition

They wore leisure suits, mood rings and platform shoes. They crowded around television sets to watch the antics of Archie and Edith Bunker on "All In The Family". They swayed to David Bowie's "Fame" and bitched and moaned over the "Return To Sender, Embargo Mail" labels on their letters during Canada's postal strike.

THE MEN'S COMPETITION

Men from Finland, France, Poland, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, Japan, Austria, Czechoslovakia, the United States and Canada competed in Edmonton but the two skaters the audience was most interested in were Toller Cranston and Ron Shaver.

Toller Cranston had won the event in 1973; Shaver was victorious in 1974. When the two Canadians last competed against each other at the World Championships in Colorado Springs, Cranston finished fourth to Shaver's eighth.

When Ron Shaver arrived in Edmonton, he was still recuperating from a serious groin injury that had nearly sidelined him the previous season. He finished only fourth in figures, behind Igor Bobrin, Toller Cranston and Hungary's László Vajda. A stumble on the second half of the double toe-loop/triple toe-loop combination and a fall at the end of his step sequence in the short program made it impossible for Shaver to move up. Toller Cranston, on the other hand, brought down the house with one of his finest performances ever. Skating to Strauss' jubilant "Graduation Ball", he dazzled the audiences and judges alike with his finesse, flair and superb technical skill.

The men's free skate in Edmonton was a nightmare for both the accountants and referee and assistant referee Sonia Bianchetti and Audrey Williams. Nineteen Terry Kubicka, the young American who had won the free skate at the 1975 World Championships and emerged as his country's 'number one' after Gordon McKellen's retirement, brought down the house with an electric routine jam-packed with triple jumps... and a not yet officially illegal but) certainly frowned upon backflip. The judges scored him just behind Ron Shaver, who landed five triples, in the free skate.

When the marks were tallied, Terry Kubicka managed to make up enough ground to finish third overall despite being only sixth entering the free skate after stepping out of a triple Lutz in the short and messing up one of his figures. Toller Cranston, though only third in the free skate with a disappointing performance that featured only one clean triple, still managed to take the gold on the strength of his figures and short program.

THE WOMEN'S COMPETITION

Edmonton born Lynn Nightingale had won both the Canadian and Skate Canada titles in 1973 and 1974 but opted to perform an exhibition instead of competing at the 1975 event. She was slated to compete at the Richmond Trophy in England that November. In her absence, the heavy favourite was Kath Malmberg, a two-time U.S. Medallist from Rockville, Illinois who had placed a strong fifth at the 1975 Worlds in Munich on the strength of her figures. To no one's surprise, she led the pack after the compulsories in Alberta. Japan's Emi Watanabe, only fourth in figures, won the short to move up to third overall entering the free skate behind Malmberg and Italy's Susanna Driano, who trained in Colorado Springs with Carlo and Christa Fassi. Watanabe trained in Toronto but went to school down in the United States.

Susanna Driano impressed many with her stamina and high energy in the free skate. Her zippy and athletic performance included a triple Salchow, three double Axels and three double Lutzes. Her only error was on a fourth double Axel attempt, which she aborted mid-air and two-footed. In comparison, Kath Malmberg's program was far less technically demanding. She 'only' did one double Axel and two double Lutzes and attempted no triples. When the judges ranked her only third in the free skate, the gold became Driano's. It was a remarkable comeback as she'd placed only tenth in the event the year prior in Kitchener.

Canadians Susan MacDonald, Camille Rebus and Kim Alletson placed fourth, sixth and seventh. MacDonald was suffering from an abscessed tooth. West Germany's Gerti Schanderl, third after the figures, dropped down to fifth overall with a disastrous free skate. A crowd favourite, Schanderl skated with an ambition one reporter from the "Manchester Guardian" described as "resembling a Panzer tank in full attack."

THE ICE DANCE COMPETITION

Dance was poised to be included at the Olympics for the first time and the discipline was going through something of a metamorphosis. At the most recent ISU Congress, the Ice Dance Technical Committee had banned vocal music and rules had been passed penalizing excessive side-by-side and shadow skating, separations, posing and ballet inspired programs. Couples were also not allowed to perform more than seven introductory steps in the compulsory dances. In "Skating" magazine, Frank Loeser stated, "Ice dancing is currently in an unusual state of happy distraction. Each dance team seems to be pursuing a distinct sort of dance with an individual style. The only problem created is one for the judges. Apart from an awareness of technical competency, one can only use personal preference for sorting out an order. The compulsory dances thankfully provide a simpler frame for judging technical ability."

Thirteen couples competed in Edmonton - the largest field to date in the burgeoning fall invitational. 1974 winners Irina Moiseeva and Andrei Minenkov didn't return to defend their title but their Soviet teammates Lyudmila Pakhomova and Aleksandr Gorshkov were on hand to give exhibitions. Hungarians Krisztina Regőczy and András Sallay, ranked sixth in the World, were forced to withdraw when Sallay injured his back picking up luggage at the airport terminal. On hand were the fourth and fifth place teams in the World - Natalia Linichuk and Gennadi Karponosov of the Soviet Union and Matilde Ciccia and Lamberto Cesarani of Italy.

Precise compulsories and a strong Rhumba OSP earned Linichuk and Karponosov a hefty lead entering the free dance. To the surprise of many, Canadians Barbara Berezowski and David Porter managed to best the Italians to take the silver on the strength of their show-stopping, four tempo free dance to "In The Mood", "Jordan's Tango", "Softly As I Leave You" and "Mambo No. 5".

The Muscovites, to the surprise of no one, took the gold with their free dance to "The Last Snow Of Spring". Americans Judi Genovesi and Kent Weigle, Poles Teresa Weyna and Piotr Bojańczyk and Canadians Susan Carscallen and Eric Gillies finished fourth through sixth. Canada's third couple, Lorna Wighton and John Dowding, were eighth. In her book "Figure Skating History: The Evolution Of Dance On Ice", Lynn Copley-Graves noted, "The winners' strength lay in their maturity - the play of man against and toward woman - plus intricate choreography." After the Sunday night exhibitions, Barbara Berezowski flew on a red-eye flight to Toronto to compete in the Miss Canada Pageant. She was the reigning Miss Toronto. David Porter joked, "If she wins, she'll have to call me Mr. Universe".

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.

Water And Ice: The Alfredo Mendoza Story

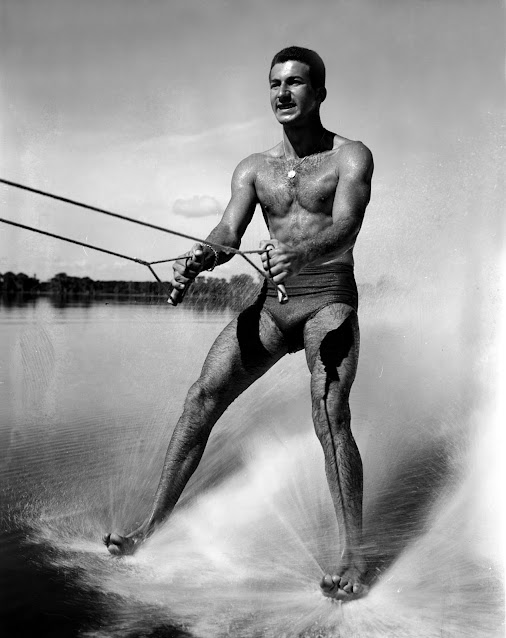

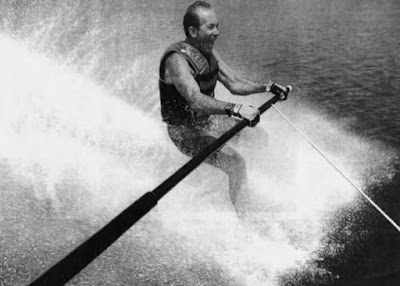

Born January 9, 1933 in Acapulco de Juárez, Mexico, Alfredo Ortiz Mendoza grew up on the water. As a boy, he learned to swim and dive off the cliffs of La Quebrada and worked on a tugboat with his older brother Carlos. Alfredo and Carlos tried their hand at bullfighting in Mexico City but ultimately it was another sport that really caught Alfredo's fancy.

After seeing a newsreel of water skiers at a local theatre, Alfredo travelled to San Juan Bautista Tequesquitengo to learn the sport on the town's lake. A year later in 1950, when Dick Pope Jr. brought his water skiing troupe to the El Paradise beach club in Acapulco, Alfredo entered his first contest and placed a creditable fourth. He caught Dick's eye and was invited to participate in a series of competitions at Cypress Gardens in Florida.

With training, Alfredo quickly rose through the water skiing ranks and won the U.S. water ski jumping tournaments in 1952 and 1953. In 1953, he won the World title in Toronto, a feat he repeated two years later in Beirut, Lebanon. After turning professional, he staged a popular show at Cypress Gardens and endorsed a line of water skis - 'The Mendoza'. In a blurb regarding his 1989 induction to the International Waterski and Wakeboarding Hall of Fame, the sport's governing body noted, "His jumping wins were characterized by an unusual 'crack-the-whip' approach to the ramp, now known as the double-wake cut. Mendoza introduced it in 1951 after he and his fellow Cypress Gardens skiers had used it successfully in practice. It enabled him to set records at the world tournaments and later became a standard for water ski jumpers of all ages."

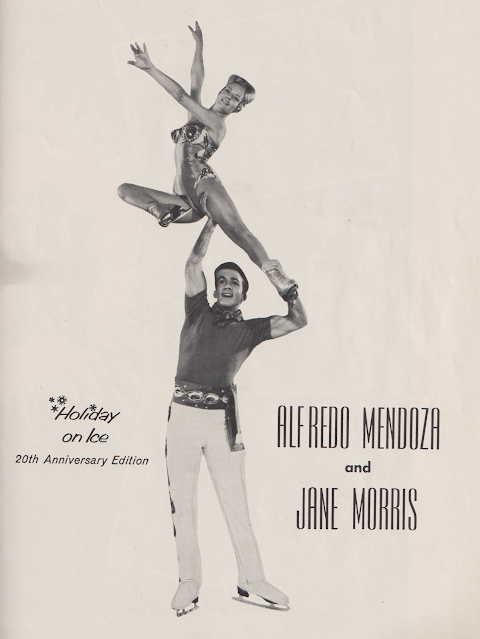

Alfredo's unlikely introduction to the sport of figure skating happened in 1955, when he was twenty years old. In a 1969 interview with a reporter from "The Tampa Tribune", he recalled, "Holiday on Ice was showing in Tampa that winter... and the star, Kay Servatius, came over to the Gardens to see them. She was gorgeous - a Ukrainian. I met her at the Gardens and she was interested in learning to water ski, which of course pleased me and Mr. Pope as well. I taught her, came to see the show at the Armoury... in Tampa and first laid eyes on an ice rink. After the show, I put on [a pair of rented] skates, got on the ice and promptly busted my confidence when I fell. I tried a couple of times, got interested and in the next few years, every chance I got, I went to Coral Gables where they had a rink and began learning to skate." The same reporter who interviewed him for that article called him a 'wetback'. Despite the discrimination he faced, Alfredo was so persistent in his efforts to learn to skate that he made the three and a half hour drive from Winter Haven to Coral Gables as often as he could. In 1957, he auditioned for Holiday On Ice and got his start in the chorus.

Alfredo's early days in the show were far from glamorous - at one point, he was selected to appear as the front half of a dog costume. Wearing a fifteen pound head, he careened around the ice to the strains of Elvis Presley's hit "Hound Dog". He recalled, "I couldn't skate worth a darn, but I was the world water ski champ. Publicity and all and they hired me. I was awful. I fell all the time. Twice, I guess, in one show was my personal record." Practicing every chance he could in between shows, he got his 'big break' when one of the male stars of the show was injured and he was picked out of fifty five other chorus skaters to replace him temporarily.

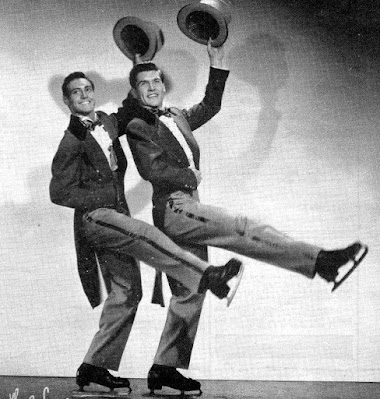

In the sixties, Alfredo became one of Holiday on Ice's biggest stars, skating adagio pairs acts with Tom Collins' future wife Janie Morris, Darolyn Prior, Carol Johnson and his own future wife, Jinx Clark. Alfredo's pairs act featured some of the most dazzling tricks of the trade, including gravity-defying carry lifts and the Detroiter. Many thought it was his skill on water skis translated to the ice, but he insisted the sports weren't similar whatsoever. "The skating is so much more difficult, really," he recalled. "Naturally, you don't have the help from the pull of the boat and the momentum for leaps and turns is all your own. Furthermore, there's always a possibility one of the girls in the show, or someone, might have dropped a bobby pin on the ice and that's some hazard."

Alfredo toured with Holiday on Ice until 1974 when, tired of the nomadic lifestyle of a touring professional, he returned to the water skiing world as a professional teacher. After returning to Cypress Gardens for a time, he operated his own water skiing schools in Clearwater and Tarpon Springs, supplementing his income by taking tourists out parasailing. In 1995, he told a reporter from "The Tampa Tribune" "I can't believe I've been doing it all this time, but it's great to be with people. I tell you, I love teaching. I think I'm a good teacher and I enjoy it."

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.

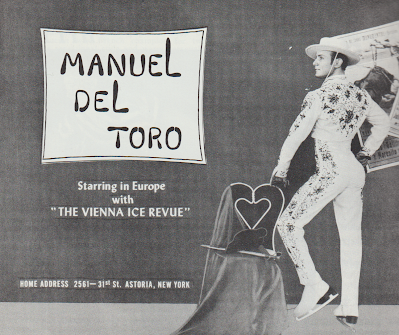

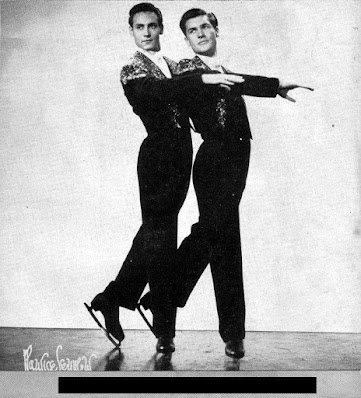

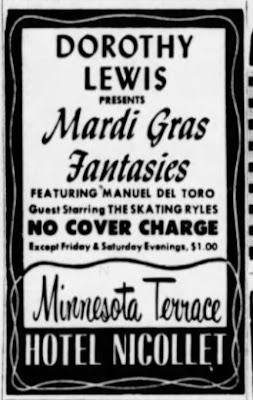

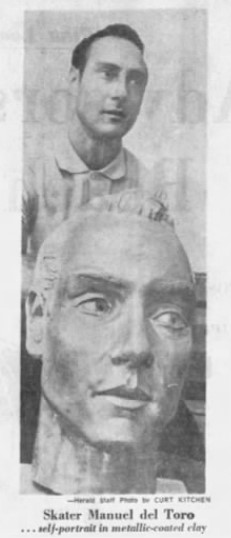

Manuel del Toro, The Puerto Rican Patinador

The son of Mercedes (Bellido) and Pedro Gregorio del Torro Gomez, Manuel del Toro was born August 3, 1927 in Brooklyn, New York. When he was a baby, his parents brought him to Puerto Rico. Manuel, his older sister Mercedes and younger brother Jorge grew up in the municipality of Mayagüez, where his father worked as a house carpenter.

The 1952 U.S. Figure Skating Championships

King George VI passed away and Princess Elizabeth was proclaimed the Queen of England. The United States senate ratified a peace treaty with Japan. Harry S. Truman was President, Brylcreem and beehives were all the rage, a movie ticket was forty cents and Kay Starr's "Wheel Of Fortune" topped the music charts.

The event was the grand finale of a long and arduous season. Most of the top skaters had already competed at the U.S. Olympic Tryouts just before Christmas in Indianapolis and at the Winter Olympic Games and World Championships, held in Oslo and Paris. Though the competition was serious business, the mild weather coupled with the popular outdoor swimming pool on the Lake Terrace of the Broadmoor Hotel provided more of a vacation vibe than anything. How did things play out on the ice? Let's take a look back!

THE NOVICE AND JUNIOR EVENTS

Los Angeles' Georgiana Sutton lead the way after the school figures in the novice women's event, but was overtaken in the free by Mary Ann Dorsey. Fourteen year old Dorsey - 'Lulu' to friends - was a ninth grade student in Minneapolis who enjoyed knitting and playing ping pong. Another ninth grade student, thirteen year old Tim Brown of Baltimore, was the unanimous winner in the novice men's event. He had only been skating for three years at that point and carried around a wishbone for good luck.

The winners of the junior pairs title were Sharon Coate and Richard 'Buddy' Bromley, teenagers from the state of Washington. Coate and Bromley were competitors in singles, pairs and dance and represented two different clubs - she Seattle; he the Lakewood Winter Club in Tacoma. He was the editor-in-chief of his high school newspaper; she collected dolls from around the world. Finishing just off the podium in fourth were Carol Ann Peters and Danny Ryan, who skated 'double duty' in the Gold (senior) Dance event.

The Silver (junior) Dance event was won by a husband and wife team from Buffalo, Elizabeth and Roger Chambers. They had both been skating for around ten years; competitively for four. She was a mother of three and he worked in the sales department of Maxson Cadillac. Both were keen amateur photographers and were quite tall for dancers at the time. She was five foot six; he six foot one.

Though she had just won the Eastern title in the senior category, twelve year old Carol Heiss competed as a junior in Colorado Springs. She represented the Junior Skating Club of New York and came behind from third in figures to convincingly win the junior women's event. In doing so, she added her name to a long list of U.S. women who'd claim national titles as both a junior and senior... Tenley Albright, Gretchen Van Zandt Merrill, Yvonne Sherman, Beatrix Loughran and Maribel Vinson among them. In her 2012 interview with Allison Manley on The Manleywoman SkateCast, Heiss recalled, "It was my first time dealing with the altitude. And I was third in school figures, and I remember thinking that I would have to work hard on them to get better. And I remember walking in and slamming the big arena doors on my finger. Even today it’s a little crooked, so I must have broken it."

When fourteen year old Ronnie Robertson, a ninth grade student at a progressive school in Colorado Springs, won the junior men's school figures, some thought his road to gold would be a cakewalk. It was anything but. He faced a serious challenge in the free skate from Cleveland's David Jenkins and California's Armando Rodriguez. When the marks were tallied, three judges had Robertson first, one voted for Rodriguez and another gave his first place ordinal to Philadelphia's William Lemmon Jr. - who ended up only seventh overall. The red-haired Robertson took the gold, followed by Rodriguez and Jenkins... and everyone agreed that the future of men's figure skating in America looked very bright indeed.

THE PAIRS COMPETITION

Only two pairs competed for the Henry Wainwright Howe Memorial Trophy in the senior pairs event. To no one's surprise, Karol and Peter Kennedy easily defeated Minnesota's Janet Gerhauser and John Nightingale to win their fifth and final U.S. title. Though there was no controversy in hthe judging - all five judges had the Kennedy's first - but behind the scenes there was a very different story going on.

The February 28, 1952 issue of "The Seattle Daily Times" reported, "Dr. Michael Kennedy of Seattle and his son were involved in a fist fight with a French news cameraman tonight at the World Figure Skating Championship and were separated by police. The incident came as Peter and his sister, Karol, had left the ice after finishing their pair-skating routine. As they left the ice, Karol stepped to the side of the rink and sat down to catch her breath. Dr. Kennedy said he asked the photographer not to take her picture because she was crying, but the picture was made anyway. In the melee that followed, the doctor's glasses were broken and the cameraman received a bloody nose. The police stepped in. The Kennedys hurried from the Sports Palace by a rear door and were taken to their hotel. Peter and Karol didn't wait to change to their street clothes."

In the months that followed, the ISU had its Congress and the USFSA its Annual General Meeting. It came out that in addition to the incident in Paris, Karol and Peter had also skated an exhibition without a proper sanction in Garmisch-Partenkirchen following the World Championships. The incident in question was a performance for American G.I.'s during a Bavarian skating competition, arranged by the U.S. military. Their father believed the German sponsors had applied for a sanction from the ISU, but they hadn't. Newspapers reported the exhibition as being the reason for their suspension, but the USFSA and ISU also acknowledged the incident in Paris.

Though Karol and Peter's father had told the press that they intended to skate professionally, after the suspension Peter applied to his local draft board for induction to go fight in the Korean War. He was rejected because he had asthma. He had previously been given a deferment because he was a student at the University of Washington. He got a job at the First National Bank.

THE ICE DANCE COMPETITION

Six couples competed for the Harry E. Radix Trophy in Gold (senior) Dance in Colorado Springs, with two pairings eliminated after the initial round. The unanimous winners, to the surprise of few, were Baltimore's Lois Waring and Michael McGean. They had won the event previously in 1950 but opted not to compete the year prior and were also victors at the ISU's International Ice Dance Competition at the 1950 World Championships in London. Their free dance (rather daringly) included a couple of very small lifts.

THE WOMEN'S COMPETITION

After losing to Sonya Klopfer at the U.S. Olympic Trials in Indianapolis, sixteen year old Manter Hall School student Tenley Albright of Boston had claimed the silver medal at the Winter Olympic Games in Oslo and withdrawn from the World Championships in Paris due to a serious bronchial infection. Sufficiently recovered to compete in Colorado Springs, Albright easily won her first of five consecutive U.S. titles, leading the field of six from start to finish. She also earned the Oscar L. Richard Trophy, awarded to the most artistic 'lady' skater.

THE MEN'S COMPETITION

"A superbly built athlete of immense strength, as lithe as a panther, he is concerned with his figure skating, as an endeavour to reach even greater heights. A terrific worker, he trains has few athletes have ever trained before and anyone who has seen him skate must surely realize how necessary this hard training is in order to attain such exceptional brilliance and to perform his amazing programme". These were the words of famed British skater, judge and writer T.D. Richardson, describing two time Olympic Gold Medallist, five time World Champion and three time North American Champion Dick Button. It was a delight to the skating community that Button gave "perhaps the greatest free style exhibition of his career" (according to Mrs. R. Sanders Miller in "Skating" magazine) to win his seventh consecutive U.S. title in Colorado Springs. In his final competition as an amateur, Button put the boots to his competition in the figures and landed a triple loop and three double Axels to earn unanimous first place votes from every judge and the Oscar L. Richard Trophy for the most artistic performance by a male skater. Jimmy Grogan, the winner of the U.S. Olympic Trials (which Button hadn't competed in) took the silver, ahead of Hayes Alan Jenkins, Dudley Richards and Hugh Graham. The standard of skating was so high that any other year, any of the five competitors could have easily won.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.

The Whiz Of White Lodge: The Winsome Thackeray Story

The daughter of James and Esther (Anderson) Thackeray, Esther Winsome Lorraine Thackeray was born in 1908 in Melbourne, Australia. Winsome and her three brothers William, Robert and James grew up wanting for very little at the family's large home 'White Lodge' on Marine Parade in St. Kilda.

Winsome became a member of East St. Kilda junior auxiliary of the Women's Hospital and earned a cooking diploma after taking a three year course in Domestic Arts at the Emily McPherson College of Domestic Economy. In 1927, at the age of nineteen, she was finally able to achieve some semblance of control over her destiny. She showed up on the doorstep of the famed Melbourne Glaciarium and fell madly in love with figure skating. By 1930, she was skating every single day and had passed her third class test. In an interview with Beatrice Fischer in the August 21, 1930 issue of "Table Talk" she explained, "I just couldn't bear to let anything beat me! And watching those more fortunate individuals who could cut all kinds of patterns on the ice with such apparent ease, only goaded me on to do to the same. I found, that once on the ice, it was not so very difficult to make a beginning, be it ever so bad, and then after each trial I noticed an improvement, which added to my zest and gave me an exhilirating sense of power. It is a marvellous feeling in any form of activity, but particularly with skating, when it becomes quite intoxicating."

Finding an unlikely partner in Cyril MacGillicuddy, a doctor almost twenty years her senior, Winsome entered every pairs, Waltzing and singles skating competition imaginable in Australia in the late twenties and early thirties... and placed in the top three in almost every one. Contrasting with her curly fair hair, she always skated in all black and wore a short dress with a flared skirt. She added a hat and stockings for exhibitions. In 1933 - her most successful year - she won the national women's and pairs titles in Sydney and the Victorian women's, pairs and waltzing titles in Melbourne, setting a record for the most Australian skating titles held by any person at the same time. In total, she won two Australian women and pairs titles and one Australian Waltzing title. In 1935, she again made history by becoming the first woman in Victoria to pass the first class skating test. Quoted in the September 24, 1935 issue of "The Argus", she explained, "I love skating and it is a great joy to me to be able to be on the ice nearly every day." What made Winsome's achievements all the more heartening was the fact that at the height of her success, she was grieving the death of her father.

Though she retired from competitive figure skating in 1935, Winsome remained a fixture at the Melbourne Glaciarium, helping to organize charity skating galas for the Women's Hospital and performing in carnivals as part of the 'Glaciarium Eight' (a team of two fours) with Edith Adams, Alison Lyons, Gwen Chambers, Graham Hobbs, Nate Walley, Ron Chambers and Jack Gordon. Though coverage of figure skating competitions was scant in the Australian press at the time, numerous mentions were made of Winsome's elegance and grace on the ice. She told Beatrice Fischer, "I really think my dancing helped me tremendously with skating. It is quite noticeable that those who have never danced make very much slower progress on the ice, than others who have. Dancing seems to instil a certain balance and poise, which is so necessary to possess in order to become a graceful skater."

By the time World War II started, Winsome had hung up her skates. She returned to the life her mother had charted out for her - volunteer work, volunteer work and more volunteer work. She worked tirelessly with the St. Kilda League Of Helpers and the Mission of St. James and St. John and lived a relatively quiet life. In 1947, her partner and friend Dr. MacGillicuddy passed away and on Good Friday in 1963, the long vacant Melbourne Glaciarium burned to the ground. Winsome never married and lived at 'White Lodge' her entire life, dying in relative obscurity at the age of sixty-eight on March 26, 1976... exactly forty years after she made first made Australian figure skating history.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.

A Touch Of Triskaidekaphobia

|

Year |

Men |

Women |

Pairs |

Ice Dance |

|

1928 |

Montgomery Wilson |

Edel Randem |

Kathleen Lovett and A. Proctor Burman |

N/A |

|

1932 |

(none) |

Elizabeth Fisher |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1936 |

Erle Reiter |

Angela Anderes |

Irina Timcic and Alfred Eisenbeisser-Ferraru |

N/A |

|

1948 |

Zdeněk Fikar |

Dagmar Lerchová |

Grazia Barcellona and Carlo Fassi |

N/A |

|

1952 |

Kalle Tuulos |

Vevi Smith |

Bjørg Skjælaaen and Reidar Børjeson |

N/A |

|

1956 |

Allan Ganter |

Joan Haanappel |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1960 |

Peter Jonas |

Dany Rigoulot |

Marcelle Matthews and Gwyn Jones |

N/A |

|

1964 |

Charles Snelling |

Kumiko Okawa |

Margit Senf and Peter Göbel |

N/A |

|

1968 |

Philippe Pélissier |

Linda Carbonetto |

JoJo Starbuck and Ken Shelley |

N/A |

|

1972 |

Didier Gailhaguet |

Cathy Lee Irwin |

Florence Cahn and Jean-Roland Racle |

N/A |

|

1976 |

Pekka Leskinen |

Emi Watanabe |

Ingrid Spieglová and Alan Spiegl |

Susan Carscallen and Eric Gillies |

|

1980 |

Rudi Cerne |

Karin Riediger |

(none) |

(none) |

|

1984 |

Mark Cockerell |

Elizabeth Manley |

Claudia Massari and Leonardo Azzola |

Jindra Holá andd Karol Foltán |

|

1988 |

Petr Barna |

Charlene Wong |

Lisa and Neil Cushley |

Sharon Jones and Paul Askham |

|

1992 |

Masakazu Kagiyama |

Patricia Neske |

Danielle and Stephen Carr |

Anna Croci and Luca Mantovani |

|

1994 |

Michael Tyllesen |

Lenka Kulovaná |

Anuschka Gläser and Axel Rauschenbach |

Aliki Stergiadu and Juris Razgulajevs |

|

1998 |

Szabolcs Vidrai |

Shizuka Arakawa |

Danielle McGrath and Stephen Carr |

Kateřina Mrázová and Martin Šimeček |

|

2002 |

Ivan Dinev |

Sarah Meier |

Tiffany Scott and Philip Dulebohn |

Sylwia Nowak and Sebastian Kolasiński |

|

2006 |

Emanuel Sandhu |

Susanna Pöykiö |

Marcy Hinzmann and Aaron Parchem |

Federica Faiella and Massimo Scali |

|

2010 |

Artem Borodulin |

Min-jeong Kwak |

Caydee Denney and Jeremy Barrett |

Nóra Hoffmann and Maxim Zavozin |

|

2014 |

Brian Joubert |

Kaetlyn Osmond |

Maylin and Daniel Wende |

Sara Hurtado and Adrià Díaz |

|

2018 |

Daniel Samohin |

Ha-nul Kim |

Tae-ok Ryum and Ju-sik Kim |

Kana Muramoto and Chris Reed |

|

2022 |

Deniss Vasiljevs | Viktoriia Safonova | Nicole Della Monica and Matteo Guarise | Marjorie Lajoie and Zachary Lagha |

|

Year |

Men |

Women |

Pairs |

Ice Dance |

|

1914 |

Sergei Wanderfliet |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1922 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1923 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1924 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) | N/A |

|

1925 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1926 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1927 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1928 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1929 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1930 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1931 |

Theo Lass |

(none) |

(none) | N/A |

|

1932 |

(none) |

Elizabeth Fisher |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1933 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) | N/A |

|

1934 |

(none) |

Ester Bornstein |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1935 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1936 |

Toshikazu Kagiyama |

Audrey Peppe |

(none) | N/A |

|

1937 |

(none) |

(none) |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1938 |

(none) |

(none) |

A. Wächter and Fritz Lesk |

N/A |

|

1939 |

(none) |

Britta Rahlen |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1947 |

(none) |

Gun Ericson |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1948 |

Per Cock-Clausen |

Suzanne Morrow |

Joan Ogilvie and Bobby Thompson |

N/A |

|

1949 |

(none) |

Beryl Bailey |

(none) |

N/A |

|

1950 |

(none) |

Valda Osborn |

(none) |

(none) |

|

1951 |

(none) |

Betty Hiscock |

(none) |

(none) |

|

1952 |

(none) |

Eva Weidler |

(none) |

(none) |

|

1953 |

György Czakó |

Elaine Skevington |

(none) |

(none) |

|

1954 |

(none) |

Rosi Pettinger |

(none) |

(none) |

|

1955 |

Tilo Gutzeit |

Ilse Musyl |

(none) |

Claude Weinstein and Claude Lambert |

|

1956 |

Hans Müller |

Fiorella Negro |

(none) |

Lucia Fischer and Rudolf Zorn |

|

1957 |

Yukio Nishikura |

Joan Haanappel |

(none) |

(none) |

|

1958 |

Norbert Felsinger |

Margaret Crosland |

Ludmila Belousova and Oleg Protopopov |

Adriana Giuggiolini and Germano Ceccattini |

|

1959 |

Hubert Köpfler |

Carla Tichatschek |

(none) |

(none) |

|

1960 |

Hubert Köpfler |

Sonia Snelling |

(none) |

(none) |

|

1962 |

Sepp Schönmetzler |

Eva Grožajová |

Mieko Otwa and Yutaka Doke |

Marlise Fornachon and Charly Pichard |

|

1963 |

Hugo Dümler |

Karen Howland |

(none) |

Helga and Hannes Burkhardt |

|

1964 |

Robert Dureville |

Kumiko Okawa |

(none) |

Diane Towler and Bernard Ford |

|

1965 |

Tim Wood |

Hana Mašková |

Ingrid Bodendorff and Volker Waldeck |

Gabriele Rauch and Rudi Matysik |

|

1966 |

Robert Dureville |

Sally-Anne Stapleford |

Susan and Paul Huehnergard |

Annerose Baier and Eberhard Rüger |

|

1967 |

Sergei Chetverukhin |

Rita Trapanese |

Betty Lewis and Richard Gilbert |

Lyudmila Pakhomova and Aleksandr Gorshkov |

|

1968 |

Michael Williams |

Linda Carbonetto |

Betty and John McKilligan |

Donna Taylor and Bruce Lennie |

|

1969 |

Tsuguhiko Kozuka |

Rita Trapanese |

Evelyne Schneider and Willy Bietak |

Ilona Berecz and István Sugár |

|

1970 |

Toller Cranston |

Charlotte Walter |

Evelyne Scharf and Willy Bietak |

Teresa Weyna and Piotr Bojańczyk |

|

1971 |

Jacques Mrozek |

Kazumi Yamashita |

Linda Connolly and Colin Taylforth |

Anne-Claude Wolfers and Roland Mars |

|

1972 |

Didier Gailhaguet |

Gerti Schanderl |

Gabriele Cieplik and Reinhard Ketterer |

Teresa Weyna and Piotr Bojańczyk |

|

1973 |

László Vajda |

Gerti Schanderl |

Gale and Joel Fuhrman |

Krisztina Regőczy and András Sallay |

|

1974 |

Bernd Wunderlich |

Barbara Terpenning |

Florence Cahn and Jean-Roland Racle |

Anne and Harvey Millier |

|

1975 |

Didier Gailhaguet |

Emi Watanabe |

Grażyna Kostrzewińska and Adam Brodecki |

Susan Carscallen and Eric Gillies |

|

1976 |

Christophe Boyadjian |

Karena Richardson |

Gabrielle Beck and Jochen Stahl |

Judi Genovesi and Kent Weigle |

|

1977 |

Kurt Kurzinger |

Heather Kemkaran |

Kyoko Hagiwara and Sumio Murata |

Susi and Peter Handschmann |

|

1978 |

Konstantin Kokora |

Claudia Kristofics-Binder |

Gabrielle Beck and Jochen Stahl |

Stefania Bertele and Walter Cecconi |

|

1979 |

Brian Pockar |

Natalia Strelkova |

Elizabeth and Peter Cain |

Karen Barber and Nicky Slater |

|

1980 |

Jean-Christophe Simond |

Carola Weißenberg |

Susan Garland and Robert Daw |

Marie McNeil and Rob McCall |

|

1981 |

Falko Kirsten |

Manuela Ruben |

(none) |

Marie McNeil and Rob McCall |

|

1982 |

Grzegorz Filipowski |

Elizabeth Manley |

Luan Bo and Yao Bin |

Wendy Sessions and Stephen Williams |

|

1983 |

Gary Beacom |

Sanda Dubravčić |

Susan Garland and Ian Jenkins |

Judit Péterfy and Csaba Bálint |

|

1984 |

Mark Cockerell |

Karin Telser |

(none) |

Isabella Micheli and Roberto Pelizzola |

|

1985 |

Petr Barna |

Susan Jackson |

Shuk-Ling Ngai and Kwok-Yung Mak |

Noriko Sato and Tadayuki Takahashi |

|

1986 |

Grzegorz Filipowski |

Agnès Gosselin |

Kerstin Kimminus and Stefan Pfrengle |

Sharon Jones and Paul Askham |

|

1987 |

Falko Kirsten |

Claudia Villiger |

Shuk-Ling Ngai and Cheuk-Fai Lai |

Sharon Jones and Paul Askham |

|

1988 |

Neil Paterson |

Yvonne Gómez |

Anuschka Gläser and Stefan Pfrengle |

April Sargent and Russ Witherby |

|

1989 |

Axel Médéric |

Yvonne Pokorny |

(none) |

Susanna Rahkamo and Petri Kokko |

|

1990 |

Oliver Höner |

Beatrice Gelmini |

Sharon Carz and Doug Williams |

Małgorzata Grajcar and Andrzej Dostatni |

|

1991 |

Oliver Höner |

Simone Lang |

Cheryl Peake and Andrew Naylor |

Małgorzata Grajcar and Andrzej Dostatni |

|

1992 |

Michael Slipchuk |

Tatiana Rachkova |

Anuschka Gläser and Stefan Pfrengle |

Anna Croci and Luca Mantovani |

|

1993 |

Konstantin Kostin |

Lisa Ervin |

Svetlana Pristav and Viacheslav Tkachenko |

Margarita Drobiazko and Povilas Vanagas |

|

1994 |

Aren Nielsen |

Rena Inoue |

Natalia Krestianinova and Alexei Torchinski |

Irina Lobacheva and Ilya Averbukh |

|

1995 |

Vasili Eremenko |

Marina Kielmann |

Marina Khalturina and Andrei Krukov |

Elizaveta Stekolnikova and Dmitri Kazarlyga |

|

1996 |

Takeshi Honda |

Tatiana Malinina |

Dorota Zagórska and Mariusz Siudek |

Kati Winkler and René Lohse |

|

1997 |

Laurent Tobel |

Nicole Bobek |

Silvia Dimitrov and Rico Rex |

Kateřina Mrázová and Martin Šimeček |

|

1998 |

Michael Tyllesen |

Joanne Carter |

Marsha Poluliaschenko and Andrew Seabrook |

Elena Grushina and Ruslan Goncharov |

|

1999 |

Stefan Lindemann |

Lucinda Ruh |

Valerie Saurette and Jean-Sébastien Fecteau |

Galit Chait and Sergei Sakhnovski |

|

2000 |

Vitali Danilchenko |

Sabina Wojtala |

Kateřina Beránková and Otto Dlabola |

Anna Semenovich and Roman Kostomarov |

|

2001 |

Sergei Rylov |

Tatiana Malinina |

Inga Rodionova and Andrei Krukov |

Isabelle Delobel and Olivier Schoenfelder |

|

2002 |

Brian Joubert |

Zuzana Babiaková |

Yuko Kawaguchi and Aleksandr Markuntsov |

Tanith Belbin and Benjamin Agosto |

|

2003 |

Ryan Jahnke |

Ludmila Nelidina |

Jacinthe Larivière and Lenny Faustino |

Kristin Fraser and Igor Lukanin |

|

2004 |

Ben Ferreira |

Sarah Meier |

Kathryn Orscher and Garrett Lucash |

Svetlana Kulikova and Vitali Novikov |

|

2005 |

Ivan Dinev |

Idora Hegel |

Marilyn Pla and Yannick Bonheur |

Kristin Fraser and Igor Lukanin |

|

2006 |

Tomáš Verner |

Mira Leung |

Marilyn Pla and Yannick Bonheur |

Christina and William Beier |

|

2007 |

Christopher Mabee |

Elena Sokolova |

Dominika Piątkowska and Dmitri Khromin |

Anna Cappellini and Luca Lanotte |

|

2008 |

Adrian Schultheiss |

Valentina Marchei |

Laura Magitteri and Ondřej Hotárek |

Ekaterina Bobrova and Dmitri Soloviev |

|

2009 |

Sergei Voronov |

Susanna Pöykiö |

Stacey Kemp and David King |

Alexandra and Roman Zaretski |

|

2010 |

Denis Ten |

Alena Leonova |

Anaïs Morand and Antoine Dorsaz |

Ekaterina Rubleva and Ivan Shefer |

|

2011 |

Ryan Bradley |

Cynthia Phaneuf |

Zhang Yue and Wang Lei |

Cathy and Chris Reed |

|

2012 |

Adam Rippon |

Elena Glebova |

Maylin Hausch and Daniel Wende |

Kharis Ralph and Asher Hill |

|

2013 |

Andrei Rogozine |

Alena Leonova |

Marissa Castelli and Simon Shnapir |

Penny Coomes and Nicholas Buckland |

|

2014 |

Ivan Righini |

Gabby Daleman |

Maylin and Daniel Wende |

Gabriella Papadakis and Guillaume Cizeron |

|

2015 |

Sergei Voronov |

Anna Pogorilaya |

Lubov Iliushechkina and Dylan Moscovitch |

Alexandra Paul and Mitch Islam |

|

2016 |

Alexei Bychenko |

Nicole Rajičová |

Tarah Kayne and Danny O'Shea |

Laurence Fournier Beaudry and Nikolaj Sørensen |

|

2017 |

Moris Kvitelashvili |

Anna Pogorilaya |

Nicole Della Monica and Matteo Guarise |

Laurence Fournier Beaudry and Nikolaj Sørensen |

|

2018 |

Keiji Tanaka |

Nicole Schott |

Annika Hocke and Ruben Blommaert |

Marie-Jade Lauriault and Romain Le Gac |

|

2019 |

Moris Kvitelashvili |

Ekaterina Ryabova |

Minerva Hase and Nolan Seegert |

Lilah Fear and Lewis Gibson |

|

2021 |

Han Yan |

Madeline Schizas |

Annika Hocke and Robert Kunkel |

Shiyue Wang and Xinyu Liu |

|

2022 |

Deniss Vasiljevs |

Ekaterina Kurakova |

(none) |

Natálie Taschlerová and Filip Taschler |

|

2023 |

Deniss Vasiljevs |

Madeline Schizas |

Daria Danilova and Michel Tsiba |

Maria Kazakova and Georgy Reviya |