Photo courtesy Muzeo Collezione Salce

The year was 1954 and from January 29 to 31, seventy-four talented skaters from ten countries gathered in the city of Bolzano, nestled in the Tyrolean Mountains, to compete in the European Figure Skating Championships. Organized by the Federazione Italiana Sport del Ghiaccio in conjunction with the Societa Polisportiva Alto Adige, the event was only the third ISU Championship to be held in Italy. It was held at the Palazzo del Ghiaccio di Bolzano, which only opened the November prior. Let's take a little trip back through time and explore the stories and skaters that shaped this event!

THE WOMEN'S COMPETITION

With a whopping twenty two entries, the women's event in Bolzano was by far the most time consuming. Valda Osborn, the defending European Champion, had turned professional and the runner-up in 1953, Germany's Gundi Busch, was considered a heavy favourite. Eighteen year old Busch unanimously won the school figures by quite a wide margin, but not everyone was entirely impressed. In "Skating World" magazine, Captain T.D. Richardson wrote, "There are many who will assert that her methods in the school are to say the least unorthodox - and I must admit that once or twice I wondered how the resultant tracings on the ice could possibly justify the marks she received. That they did satisfy the judges, however, was obvious by the commanding lead she received."

Erica Batchelor. Right photo courtesy "Skating World" magazine.

In the free skate, Erica Batchelor (the bronze medallist in 1953) gave perhaps the cleanest performance. Her teammate, fourteen year old

Yvonne Sugden, arguably delivered the most difficult. Gundi Busch took a nasty fall on a double flip and went on to make several other small errors. The judges seemingly overlooked this, placing her decisively first anyway. The Swiss judged tied Erica Batchelor with Gundi Busch in free skating; British judge

Mollie Phillips had Busch tied with Yvonne Sugden. The rest of the judges were all over the place. Two judges had Austria's Annelies Schilhan second; another had her in a tie for tenth. Nelly Maas, a promising young Dutch skater, had marks ranging from second to seventh and the third British entry, Brighton's Clema 'Winkie' Cowley, was placed fourth by the Swiss judge... and sixteenth by the Italian. When the marks were tallied, Gundi Busch came out on top - making history as the first German to win the European women's title. The silver went to Erica Batchelor; the bronze to Yvonne Sugden. In nineteenth place was another young talented young Dutch skater - Sjoukje Dijkstra.

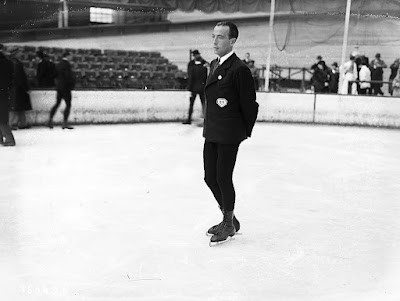

THE MEN'S COMPETITION

The previous year in Dortmund, Carlo Fassi had made history as the first Italian skater to win the European title. His superb school figures in Bolzano earned him first place marks from all but the Czechoslovakian judge, who had Karol Divín in first place. While Fassi was widely praised for his precision in the figures, the young Frenchman in second Alain Giletti was not. Captain T.D. Richardson wrote, "I thought his school was definitely over-marked. Looking down from the balcony, for example, onto the three-change-three, I, with a number of others thought that most of the 'lines in' were on the flat. And I detest 'double tracking' - a heinous fault of which no one could accuse our British skaters, or those trained in Britain either - although it was much in evidence amongst many of the others. In this regard I kept wondering what the ex-professional teacher [Werner] Rittberger must have thought of this - for he was on the ice as an official most of the time. I know what his brother professionals, off the ice, thought."

If some of the judges might have had misgivings about Alain Giletti's figures, they didn't about his free skating. Five out of the seven judges had him in first. The Italian judge had Carlo Fassi first and Giletti fourth. The Swiss judge had Karol Divín first and Giletti and Fassi tied for second. Both Giletti and Fassi skated extremely well, but Karol Divín missed several jumps. When the marks were tallied, Fassi repeated as European Champion with Giletti second and Divín third. Only three points separated the top two skaters.

The Swiss judge who placed Karol Divín first faced jeers from the audience. Some questioned how even medalled at all, because his figures weren't particularly outstanding as compared to sixteen year old Michael Booker, who placed fourth. He earned the bronze based on his ordinal placings; Booker had more points. Alain Calmat, who placed fifth, had his trip to Bolzano paid for by World Champion

Jacqueline du Bief. She donated all proceeds from an exhibition given at the Palais de Glace in Paris to pay for his travel expenses to Europeans and Worlds.

THE ICE DANCE COMPETITION

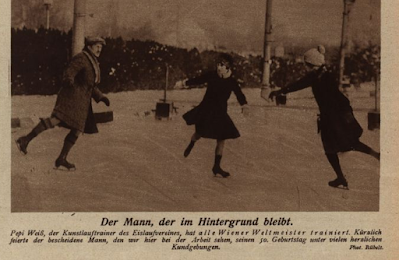

Jean Westwood and Lawrence Demmy. Photo courtesy "Skating World" magazine.

Twelve couples entered the first ever European Championships in ice dance. Defending World Champions

Jean Westwood and Lawrence Demmy took a decisive lead in the compulsory dances, to no one's surprise whatsoever.

A last-minute schedule change just before the free dance made for utter chaos for judges and skaters alike. Cyril Beastall recalled, "There [also] appears to have been some confusion in the arrangements for dance and pair skating at Bolzano, causing upset among the competitors. We are not disputing the advertised right of the authorities to change the programme, but at the same time the competitions should be run for the skaters? The draw, originally, for dance and pairs was scheduled for 8 p.m., and the pair skating was advertised to take place at 9 p.m. After waiting twenty minutes, the pairs left for the rink, to change and be ready for the run round. It was only at 8:25 that the VIP's appeared, and then announced that the dancing would be first at 9 p.m., followed by the pairs. Experience should have indicated that this would result in considerable confusion. At the rink, some of the dancers were ready and some were not. We were sorry to hear from Mme. Meudec's experience - after being told the same afternoon that no change of programme was contemplated, she arrived in good time, as she thought only to be sent away because the competition had started! Hardly efficient or courteous by ordinary standards?" Mme. Henri Meudec, the French judge who had judged the compulsory dances, was replaced in the free dance by an Italian judge.

Jean Westwood and Lawrence Demmy earned unanimous first place marks in the free dance to easily win the first European dance title over their teammates Nesta Davies and Paul Thomas and Barbara 'Bunty' Radford and Raymond Lockwood. It was the first of many British medal sweeps in dance at Europeans. The Italian, Austrian and French teams ranked fourth through sixth were only separated by two ordinal placings. Bona Giammona and Giancarlo Sioli, the Italians who came fourth to the delight of the Bolzano crowd, moved all the way up from seventh after compulsories - but received tenth place marks from the Austrian judge.

Captain T.D. Richardson couldn't help but rave about Jean Westwood and Lawrence Demmy's winning performance. He remarked, "They are excellent in the compulsory dances; but it is in the free that they are outstanding. To start with, their programme bears a mark of genius in its general arrangement and in the skill with which it enables the man to show off the lady. In this regard it much resembles the ballet wherein, in a pas de deux it is left to a great degree to the ballerina to perform the main dancing and to the male dancer to present her. I think that this feature, which some ardent skaters might consider a fault, would be noticeable only to the expert. The value of a programme of this character must be left to the technicians - few indeed in number - to assess... It was by its faultless precision a thing to wonder and rejoice at. For myself, I will travel a long way to see its like again."

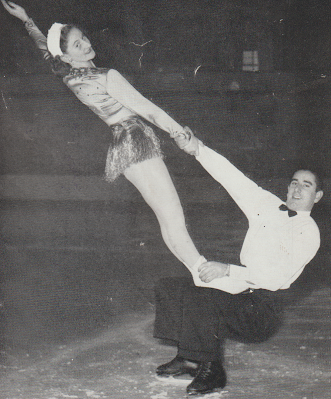

THE PAIRS COMPETITION

The absence of the top two pairs teams from the 1953 European Championships paved the way for one of the closest contests ever at Europeans in Bolzano. Austria's Sissy Schwarz and Kurt Oppelt had the most points and fewest ordinal placings, but the judging panel was split three-two in favour of Switzerland's

Silvia and Michel Grandjean, with the German, British and Swiss judges voting for the Grandjean's and the Austrian and Czechoslovakian judges voting for Schwarz and Oppelt. The Grandjean's victory was the very first gold medal at an ISU Championship in any discipline for Switzerland. The bronze medal went to Czechoslovakian siblings Soňa Balůnová and Miroslav Balůn.

Sissy Schwarz and Kurt Oppelt. Photo courtesy Bildarchiv Austria.

Captain T.D. Richardson remarked, "In this event Michel and Silvia Grandjean... thoroughly deserved their win, for they were the only pair to combine elegance and charm, gliding speed, a sufficiency of difficulty and that 'togetherness' which is the essential of pair skating. Most of their rivals indulged in a superfluity of acrobatics with little evidence of skating technique. If the judges were asking for difficulty - most of them must have been looking the other way when Bob Hudson and Jean Higson performed - for they executed movements that many of the other pairs would not have dared to attempt; and what is more, they included some very good skating. In my opinion, they should have been second - fourth place was much to low. It is true that Kurt Oppelt and [Sissy] Schwarz, who came second, have an excellent programme, but until they take the trouble to eradicate many glaring faults of position, footwork and general technique, they cannot be ranked as near-champions. The Czechoslovak pair... who came third were rough and not at all together."

The sour taste left in the mouths of the pairs skaters, ice dancers and judges after the organizer's last-minute schedule change was compounded by a minor incident at the customary closing banquet. Cyril Beastall complained, "At a party following the events at Bolzano, when those present were listening to the various speeches and in a happy atmosphere, a discordant note was introduced. The room was long and those at the far end had considerable difficulty in hearing the lengthy speeches - but on these occasions no one bothers about that. Therefore there was a buzz of conversation from the far end of the room, which members of the British party, nearly twenty strong, seated near the presentation table, could of course hear. The discordant note was introduced by Mr. Bubi (pronounced Booby) Witt, who in strident English and with flushed face proceeded to call everyone to order in the manner of a disgruntled schoolmaster. Quite a few of those present are still asking why Mr. Witt made his 'request' in English."

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on

Facebook,

Twitter,

Pinterest and

YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard,

please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating":

https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.