Two days before Christmas in 1999, two men were seen running away from an explosion outside of an apartment building in Central Moscow. The late model BMW of Maria Butyrskaya was destroyed in the blast... just days prior to the Russian Championships. Butyrskaya told reporters, "I don't see any other reason for it than jealousy, pure human jealousy... In top level sports the stakes are high and, I guess, some people were willing to go to any lengths to get me out of their way." In a 2019 interview, Butyrskaya's rival Irina Slutskaya claimed to have been questioned by authorities over the incident.

Maria Butyrskaya

At the age of twenty-six, Maria Butyrskaya was considerably older than some of her competitors when she won the 1999 World Championships in Helsinki. There were rumblings, some not so quiet, that it was time for her to step aside and let someone else have a chance at glory. When she refused to be forced out the door, she continued to dominate at the highest level internationally but lost the Russian national title she'd won six times previously three times in a row.

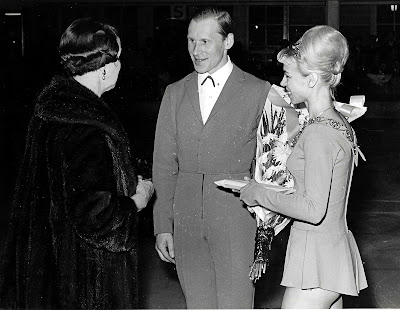

Maria Butyrskaya wasn't the first Russian skater the 'powers that be' hoped to put out to pasture. In 1964 and 1968, Ludmila (Belousova) and Oleg Protopopov won Olympic gold in Innsbruck and Grenoble. They hoped to make it a three-peat at the 1972 Games in Sapporo but upon their return to Leningrad, Soviet officials suggested they retire. When they refused, they were forced to practice on 'red eye' training sessions between midnight and two in the morning - only obtaining that time slot because a friend intervened on their behalf. The scenario was akin to a supervisor making an Employee of the Month work the graveyard shift because they didn't like them.

Ludmila and Oleg Protopopov. Photo courtesy "Ice & Roller Skate" magazine.

In 2004, Oleg Protopopov recalled, "The Soviet Figure Skating Federation [used] administrative power to [cross] out our plans, pointing out that we were too old, very theatrical, athletically weak, no speed, no difficult elements in the programs. But underneath of all this 'snow job' was the hidden rumours of our sport and administrable opponents, that Belousova-Protopopov will defect if they will win their 3rd Olympic Games. It was a real hit below the belt for everything what we did for the National sport and our Motherland." The Protopopov's ultimately defected from the Soviet Union in 1979 and enjoyed success on the professional competition circuit, taking top prize - and thousands of dollars in prize money - in events in Japan and the United States. Had the couple not defected, Oleg Protopopov's salary for coaching would have been a pittance of eighty kopecks an hour.

Kira Ivanova

Kira Ivanova wasn't as lucky as Maria Butyrskaya or Oleg and Ludmila Protopopov. Though she won the Olympic bronze medal at the 1984 Games in Sarajevo, a silver medal at the 1985 World Championships in Tokyo and four medals at the European Championships, her skating career had been one of both high's and low's. She won the school figures at the 1988 Olympic Games but finished seventh overall, unable to compete with the Battle of the Carmen's, Liz Manley and Midori Ito. At the lowest point of her career, Kira Ivanova was disqualified from the Spartakiad of the Peoples of USSR and suspended from the Soviet Union's national team after skipping a mandatory doping test.

After falling out of favour with Soviet officials, Kira Ivanova was forced to find work as a coach. In the span of a six years, she got married and divorced twice, her grandmother died and her sister committed suicide, she was in two car accidents and developed a serious drinking problem. On December 21, 2001, she was found stabbed to death in her apartment on the outskirts of Moscow. Prior to her death, things had been so dire that she sold many of her belongings, including her skating cups, trophies and medals.

Igor Pashkevich

Kira Ivanova's story might seem like an extreme example of a Russian skater's downfall, but it wasn't the only one. In recent years, two other Moscow born Olympic figure skaters - Igor Pashkevich and Ekaterina Alexandrovskaya - passed away under similarly tragic circumstances.

Canadian skating has had its own fair share of scandals over the years, but you just don't hear outrageous stories like these... and that's something worth questioning. So too is the decision made to allow Kamila Valieva to compete in the women's event at the 2022 Winter Olympic Games after a failed doping test. CAS officials claimed her disqualification would "cause irreparable harm". She was clearly in distress after giving an uncharacteristically flawed performance today and was berated by her coach as soon as she got off the ice. Many are rightfully questioning if allowing her to continue was in fact more harmful to her mental health in the long run.

Today was a chapter in figure skating history that champions who have long departed from this earth would have shuddered at. The event was difficult to watch from start to finish and hearkened back to that iconic Canadian Heritage Moment of Agnes Macphail shouting, "Is this normal?" No, it isn't - and the sport is undoubtedly going to see sweeping changes in the months and years to come. So too are the lives of fifteen year old Kamila Valieva and the other Russian teenagers we saw skate today.

As figure skating faces its biggest reckoning in many years, we really must seriously consider the fate - and indeed safety - of these talented young skaters who were failed by everyone around them. What can they look forward to when they follow the yellow brick road back to The Land of Sambo? Will they compete again? Will they retire and show up in the audience at the next big event, mugging for television cameras and removing masks during a pandemic? Or will they fade into complete obscurity? If the latter option brings peace, perhaps that is what we should wish for.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.