Photo courtesy Canada's Sports Hall Of Fame. Used with permission.

Canada had just introduced a capital gains tax and a ban on cigarette advertisements on television, film and radio. In England, unemployment had reached the one million mark for the first time since the thirties, and a miner's strike foreshadowed the oil crisis and Three-Day Week to come. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau's son Justin was only a few months old and Bettye Lavette's cover of Neil Young's new hit song "Heart Of Gold" blared on the 8-track players of Volkswagen Beetles.

The year was 1972 and sixteen years before the Battles Of The Brians and Carmens and Liz Manley's show-stopping free skate at the 1988 Olympic Games, Albertans herded into the Stampede Corral in record numbers for the 1972 World Figure Skating Championships.

Layout of arena showing ticket prices. Tickets for school figures and practice sessions (not shown) were $1.00, payable only at the door. Photo courtesy "Skating" magazine.

George J. Blundun honoured by the city of Calgary with a plaque commemorating the 1972 World Championships in 1981. Photo courtesy "Canadian Skater" magazine.

However, when Blundun met with ISU officials at the 1968 World Championships in Geneva, he learned that Japan was considering a bid and was encouraged to bid for the 1971 World Championships instead. Though Toronto also submitted a bid, Blundun secured a twenty-two thousand dollar grant from the Province of Alberta, a one hundred and twenty thousand advance from the Royal Bank and five thousand, five hundred dollars from the city of Calgary.

In her book "Reflections On The CFSA: A History Of The Canadian Figure Skating Association 1887-1990", Teresa Moore explained that Blundun "wanted to see Canada as a major force in the skating community and the way to do that, he reckoned, was to bring the world to Canada. He was also a westerner and when he brought the world to Canada, he wanted to make sure it was Calgary they saw. He planned to hold the best World Championships the world had ever seen - not to repeat the success of Vancouver, but to outdo it. His Worlds would be like nothing anyone had ever seen. And he planned to do the unthinkable... he planned to make money doing it."

Wally Attrill, the building superintendent, spraying white paint at the Stampede Corral in preparation for the competition. Photo courtesy Glenbow Archives.

Blundun's Calgary bid beat out Toronto easily, but in June of 1968, it was announced that the 1971 World Championships would be held in Lyon, France. Unphased by the loss, Blundun applied to host the World Championships in 1972. Japan had also applied, citing the logic that it would be easier for skaters to remain in Asia following the Sapporo Olympics than to travel to another continent shortly thereafter. However, the ISU balked at the cost of holding the 1972 World Championships in Japan and finally decided to accept Blundun's bid. The good news was announced by the CFSA in June of 1970.

Photo courtesy Canada's Sports Hall Of Fame. Used with permission.

Left: Official logo of the competition. Right: Commemorative badge. Photo courtesy Alberta Sports Hall of Fame and Museum. Used with permission.

Canada Post's commemorative stamp issued in conjunction with the 1972 World Championships

The event was televised internationally on Eurovision and its Iron Curtain satellite Intervision and ABC's Wide World Of Sports. Johnny Esaw and Otto Jelinek called it for CTV. To commemorate the event, Canada Post issued a special eight-cent stamp five days before the competition. It was the first time a Canadian stamp was ever issued in conjunction with the World Figure Skating Championships.

However, not everything in Calgary was all sunshine, lollipops and rainbows. In "Skating" magazine, Nancy Gupton Aitken recalled, "In the days before the competition, everything that could go wrong, did. Music tapes broke, were spliced, and retaped. Competitors missed buses, were stuck in elevators, caught the 'flu bug', fell and were hospitalized, and misinterpreted practice schedules, but still made lifelong friends while learning each other's languages. Coaches got in the way, yelled at their skaters, and berated music operators. Parents alternately laughed and cried."

Ondrej Nepela and Trixi Schuba

With huge thanks to Lindsay Moir of the Glenbow Museum (who went above and beyond with her help with this particular blog), Canada's Sports Hall Of Fame, Marie Petrie McGillvray and the Alberta Sports Hall Of Fame, we'll explore the story of the event played out!

Photo courtesy Canada's Sports Hall Of Fame. Used with permission.

THE PAIRS COMPETITION

Pairs medallists in Calgary. Photo courtesy Marie Petrie McGillvray.

The required elements for the pairs compulsory short program were side-by-side double Salchows, a straight line step sequence, back outside death spiral, side-by-side flying camel spins and a double overhead lasso lift. Skating to "Metelitza" and "Csárdás", twenty-two year old Irina Rodnina and twenty-four year old Alexei Ulanov made history, receiving the first two 6.0's ever awarded in the pairs compulsory short program at the World Championships. One was for technical merit and the other for artistic impression.

Rodnina and Ulanov's success was remarkable in that the Sunday before the start of the competition, Rodnina was reportedly hospitalized due to a concussion and shoulder injury after a missed lift in practice. They missed two days of practice as a result. The reported concussion wasn't the only reason that Rodnina was "pale and unsteady" in Calgary. She and Ulanov were barely on speaking terms and this event was when the love triangle between Rodnina, Ulanov and Lyudmila Smirnova reached its apex. Sandra Bezic recalled that as a result, "Her 'Sad Eyes' exhibition number was never more poignant." Between the Sapporo Olympics and the Worlds in Calgary, Smirnova and her partner Andrei Suraikin had been sent back to Leningrad, skipping the exhibition at the Closing Ceremonies. When Ulanov returned, he quickly married Smirnova.

Irina Rodnina and Alexei Ulanov. Left photo courtesy Lindsay Moir, Glenbow Museum; Calgary Public Library Archives. Right photo courtesy "Skating" magazine.

Irina Rodnina struggled with her double Axel and double Salchow in the free skate, but the judges still awarded her and Ulanov 421.8 points and 9.0 ordinal placings for their effort... enough to take the overall title by a wide margin based on their result in the compulsory short program. They skated from Alexander Glazunov's "The Seasons" and Aram Khachaturian's ballet "Gayane".

Lyudmila Smirnova and Andrei Suraikin. Photo courtesy "Skating" magazine.

In what would be their final competition together, Smirnova and Suraikin skated extremely well in both phases of the competition, their only mistake being a missed double flip jump by Smirnova in the free skate. Their marks in the free skate, which ranged from 5.7 to 5.9, were comparable to Rodnina and Ulanov. JoJo Starbuck and Ken Shelley struggled on their lift in the compulsory short program but their come-from-behind free skate upstaged the Soviets. They earned two standing ovations - one after their program and another after their marks - and moved up to take the bronze. East Germans Manuela Groß and Uwe Kagelmann dropped from third to fourth, missing both throw double Axel attempts in their program.

Irina Rodnina and Alexei Ulanov. Photo courtesy Lindsay Moir, Glenbow Museum; Calgary Public Library Archives.

The UPI News Agency noted, "The Russian couple [Rodnina and Ulanov] so far outclassed other competitors with their highly original and challenging free-skating exhibition that they were unbeatable despite several stumbles by the faint Miss Rodnina. The petite skater, still pale and unsteady after a slight concussion she incurred during a practice session Saturday, had to be assisted to her dressing room following the couple's performance and a doctor waited to examine her while she returned to the podium to claim her title."

Placing fifth overall, West Germans Almut Lehmann and Herbert Weisinger thrilled the Calgary crowd with a five jump combination in their free skate set to Aaron Copeland's "Rodeo" and "Billy The Kid", but they included a cartwheel lift that some felt might have been illegal. Americans Melissa and Mark Militano finished ninth, landing a throw double Axel late in their free skate after missing one earlier in their program. In the compulsory short program, the Militanos had made an extremely unorthodox music choice, skating to the eerie soundtrack from the Alfred Hitchcock film "Psycho".

Top: JoJo Starbuck and Ken Shelley. Bottom: Melissa and Mark Militano. Photos courtesy "Skating" magazine.

THE MEN'S COMPETITION

Men's medallists. Photo courtesy Marie Petrie McGillvray.

Left: Sergei Chetverukhin. Right: Toller Cranston. Photo courtesy Lindsay Moir, Glenbow Museum; Calgary Public Library Archives.

Though Toller Cranston claimed that he "forgot how to skate" during the warm-up, he delivered one of the finest performances of his career and actually won the free skate ahead of Chetverukhin and Nepela, though Chetverukhin received two 6.0's for artistic impression to Cranston's one from Austrian judge Franz Heinlein. Cranston's performance included two clean triples and his characteristic flair, creative spins and musical brilliance. He didn't just receive a standing ovation from the Calgary crowd - he earned one. There was considerable criticism about the fact that ABC's Wide World Of Sports didn't televise his performance. The consensus was that, by excluding it, an inaccurate perspective of the competition was portrayed to the public. "Nepela, Chetverukhin and Kovalev may have won the medals," noted Nancy Gupton Aitken in "Skating" magazine, "But Cranston's performance was the story of the evening."

Ondrej Nepela and Sergei Chetverukhin. Photo courtesy "Skating" magazine.

In a column penned for the "Calgary Herald", World Champion Paul Thomas remarked, "The packed Stampede Corral was alive with anticipation Thursday evening as Canada's hope, Toller Cranston, came onto the ice to skate. And how he skated! Off to a great start with a double Axel, double Axel, and off he went... using his music well with great steps, style and poise he brought off his triple Salchow and triple loop with ease... What can one say? He received a standing ovation and moved up to fifth place from ninth, which means Canada can send a full team of men to Worlds next year."

John 'Misha' Petkevich practicing in Calgary. Photo courtesy Glenbow Archives.

Like Cranston, John 'Misha' Petkevich of the United States also turned in an outstanding free skate in Calgary. However, Nepela, Chetverukhin and Vladimir Kovalev's combined scores were still enough to keep them on the podium and Petkevich in fourth.

Canadian and American journalists struggled to explain to the public why the two brilliant North American free skaters hadn't won medals. Petkevich retired and focused his attention on his biology Ph. D. at Oxford; Cranston immersed himself in his art and regrouped for a rematch with Nepela in Bratislava the following year. The Olympic and World Champion had announced to the North American press that he wanted to retire from competition but acknowledged he was under pressure from his federation to retain his amateur status for another year and compete in the 1973 World Championships in his home country.

Ondrej Nepela, Sergei Chetverukhin and Vladimir Kovalev. Photo courtesy Lindsay Moir, Glenbow Museum; Calgary Public Library Archives.

Sergei Chetverukhin, Kenneth Shelley, Ondrej Nepela and Toller Cranston. Photo courtesy Sandra Bezic.

THE ICE DANCE COMPETITION

Ice dance medallists. Photo courtesy Marie Petrie McGillvray.

There was a great deal of speculation in Calgary as to how the ice dance competition would play out. At the European Championships in Gothenburg, West German siblings Angelika and Erich Buck simply couldn't make a mistake. Pulling off a rare upset, they handily defeated Soviets Lyudmila Pakhomova and Aleksandr Gorshkov. Seventy-five hundred spectators crowded into the Stampede Corral to watch the two teams go head-to-head in the compulsories, curious to see how things would play out in a rematch. The three compulsories drawn were the Starlight Waltz, Rhumba and Argentine Tango. It was the first time the Rhumba was skated at the World Championships. Another first in Calgary was the introduction of a rotating starting list. After each dance, the groups of skaters rotated so that no couple faced the perceived disadvantage of having to skate in the first or second group every time.

Photo courtesy Canada's Sports Hall Of Fame. Used with permission.

Pakhomova and Gorshkov and the Bucks were both less than stellar in the Starlight Waltz, with the Soviets coming out on top. The Bucks finished first in the Rhumba, though many felt that a third team, Americans Judy Schwomeyer and James Sladky should have been the winners. The Soviets rebounded to win the Argentine Tango, etching out a narrow 1.2 lead over the Bucks after the compulsories. Schwomeyer and Sladky, with 248.7 points and twenty-three ordinal placings, certainly weren't far behind the top two teams by much at all. Hal Walker, the sports editor for the "Calgary Herald", reported that the banks of lighting set up for the television crews melted a small section of the ice during one of the compulsory dances.

Lyudmila Pakhomova and Aleksandr Gorshkov. Photo courtesy "Skating" magazine.

The OSP that year was the flashy Samba, a popular choice with the Calgary crowd, and Pakhomova and Gorshkov's win in this phase of the competition only widened their overall lead. In her book "Figure Skating History: The Evolution Of Dance On Ice", Lynn Copley-Graves described the grand finale of the event - the free dance - thusly: "The Bucks performed moves aimed to excite the crowd - lifts, a fast-moving broken sit spin, and a death spiral that would count against the Duchesnays a decade and a half later. Schwomeyer/Sladky skated the most difficult of the free dances with changes of tempo and a beautiful blues section. They had never been so relaxed. The only thing wrong with their free was their marks. Pakhomova/Gorshkov skated their best free dance yet. Aleksandr, though improved, was still rough around the edges. But nobody watched him anyway... Many thought Judy and Jim should have won or at least come out ahead of the Bucks, whose program contained many illegal and questionable moves and too much arm waving, an effect most intrinsic to Eastern European style. No matter what the rules, the judges showed preference for theatrical skating and mini-pairs over dance." Canadians Louise and Barry Soper placed ninth but delighted the Calgary audience with a juxtaposition of blues and samba music. Japan's Keiko Achiwa and Yasuhiro Noto made history as the first Japanese ice dance team to compete in the World Championships. They finished dead last, almost seventy points behind winners Pakhomova and Gorshkov. Popular with the Calgary crowd, the Soviets closed the exhibition following the competition with a rousing program set to Russian folk music. They were called back for encore after encore.

Group shot following the exhibition

A noteworthy aspect of the ice dance competition was the fact the competitors - first through fifteenth places - had the same result after the compulsories and the OSP as they did overall. The only slight change was the fact that Teresa Weyna and Piotr Bojanczyk of Poland bested Anne Wolfers and Roland Mars of France by one place in the free dance, but they remained behind them in unlucky thirteenth overall. The Referee and Assistant Referee of the ice dance event were Lawrence Demmy and George J. Blundun.

Looking back at the event, Judy Sladky recalled, "We'd stayed in for 1972 in case ice dancing made it into the Olympics but it never even came up. At that point, we were getting twenty-five dollars a show and you had to pay for your food and everything else. We had to make money. We had to turn pro."

THE WOMEN'S COMPETITION

Left: Women's medallists. Photo courtesy Marie Petrie McGillvray. Right: Trixi Schuba. Photo courtesy Lindsay Moir, Glenbow Museum; Calgary Public Library Archives.

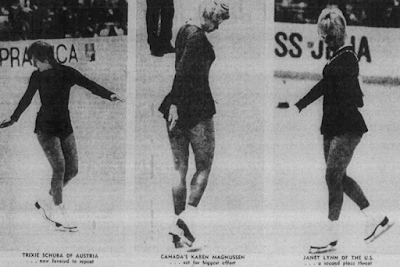

Karen Magnussen. Photo courtesy Toronto Public Library, from Toronto Star Photographic Archive. Reproduced for educational purposes under license permission.

Trixi Schuba's performance to selections from "Man Of La Mancha" only earned her the ninth-best free skating scores... but it didn't matter and she repeated as World Champion. Though defeating Schuba would have been practically impossible under the judging system in place at the time, the fact that Magnussen bridged the gap by almost one hundred points was more than impressive, especially because Lynn was the winner of the free skate. In the final tally, she was only thirty-three points behind Schuba and received first-place marks overall from three judges, including the American judge. Lynn, unable to bridge the gap, finished third with twenty-five ordinal placings and two thousand, seven hundred and thirteen points. Almassy finished in fourth, over sixty points ahead of East Germany's Sonja Morgenstern, who was third in the free skate, landing a triple Salchow. Aside from Schuba's win, another key example of the value of figures was the result of East Germany's Christine Errath. Inge Wischnewski's pupil actually finished fourth in the free skate, but an eleventh-place finish in the figures kept her in tenth overall.

Janet Lynn, Christine Errath, Trixi Schuba, Sonja Morgenstern and Janet Lynn

Dorothy Hamill, a last-minute replacement for Julie Lynn Holmes, placed fifth in the free skate and seventh overall in her first trip to the World Championships. Her program to music from Stravinsky's "The Firebird" was one of the highlights of the evening. In her book "A Skating Life: My Story", she recalled, "Somehow [my parents] made it seem as if we were on a vacation and put no pressure on me between practices. We drove up to gaze at Lake Louise and then ate at the landmark Banff Springs Hotel. I skated quite well... It probably made my mother feel vindicated about her instincts that I should have been on the Olympic team. I was the fifth-best free skater in the world. Wow! I have to admit, that was a real boost to my confidence. I had officially arrived on the international figure skating scene. Now, if I could only pass ninth-grade English!"

Top: Trixi Schuba, Karen Magnussen and Janet Lynn. Photo courtesy Lindsay Moir, Glenbow Museum; Calgary Public Library Archives. Middle: As a result of her success at the World Championships, Karen Magnussen was invited to be a special guest at the 1972 Calgary Stampede. Bottom: Janet Lynn, Trixi Schuba and Karen Magnussen backstage. Photo courtesy the 1972 ISU Tour Of Champions program.

Toronto's Cathy Lee Irwin placed ninth in her second trip to the World Championships, still recovering from an injury that had sidelined her the previous season. Sixteen-year-old Daria Prychun of Toronto, Canada's third entry in the women's event, was a last-minute replacement for an injured Ruth Hutchinson of Vancouver. She finished fifteenth of the twenty-one entries. The Referee and Assistant Referee of the women's event were Josef Dědič and Elemér Terták.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.