His Majesty King George V was Great Britain's reigning monarch, "Alexander's Ragtime Band" played on gramophones and Captain Robert Falcon Scott and his team had just become the second group in history to reach The South Pole.

The year was 1912 and much of Europe was suffering through an unseasonably cold winter. Dozens died of exposure in the Eastern part of Germany. In early February of that year, a forty-five year record low temperature was recorded in London. However bone-numbing, the subzero temperatures were optimal for skating enthusiasts.

The winter resorts of Switzerland were packed to the brim with a who's who of figure skating and on January 27 and 28 of that year, seven women took to the ice in Davos to vie for the seventh World Championship in women's figure skating, then styled as 'the ISU Championship for ladies'. At the time, it was a record number of entries for an international women's figure skating competition.

In 1952, Herbert G. Clarke recalled, "In those days it was not considered necessary to skate the compulsory figures on clean ice. The whole rink was open to the public until about 10:30 AM when a few chairs were placed on the ice to mark the space reserved for the Championship figures, and a few skaters, of which I was one, were asked to patrol the ice to see that the competitors were not obstructed by other skaters. I have never seen this happen since."

In the absence of Lili Kronberger who had won the event the previous four years, the favourite was Transylvanian born Zsófia Méray-Horváth, who had finished second to Kronberger the previous year in Vienna. However, for the first time since Madge Syers' retirement from the sport in 1908, British skaters had arrived to give the Continental women a run for their money. Méray-Horváth decisively won the school figures with first place marks from four of the five judges. British judge John Keiller Greig stood alone in placing the three British women competing - Dorothy Greenhough Smith, Gwendolyn Lycett and Phyllis (Squire) Johnson - ahead of the reigning World Silver Medallist. In the free skate, Méray-Horváth built upon what was already a firm lead. One of the two Swiss judges and Greig tied her for first with Greenhough Smith and the second Swiss judge gave the nod to Johnson but first place ordinals from the French and Austrian judges assured her a winning placement in both the free skate and overall. Greenhough Smith settled for silver, ahead of Johnson, Lycett, Germany's Grete Strasilla, Austria's Mizzi Wellenreiter and German born Ludovika (Eilers) Jakobsson. In conjunction with the event, an international competition for junior skaters was held in Davos with British skater Basil Williams (representing St. Moritz) taking top honours ahead of six other skaters hailing from Germany, Great Britain and France. There was also a waltzing contest, won by Daphne Wrinch and Herr H. Jensen. Arthur Cumming and Lady Cadogan were second; Gwendolyn Lycett and Louis Magnus third.

On February 16 and 17, 1912, the newly constructed Manchester Ice Palace in England played host to the World Championships in men's and pairs skating. Though unable to attend, Irving Brokaw of New York received an invitation to participate. This invitation marked the first time an American skater was offered a chance to compete at the World Championships and was significant in that at the time, the U.S. wasn't even a member of the ISU. Brokaw's invitation was likely based on his strong ties to Switzerland and his advocacy in bringing the Continental (or International) Style to America.

To the delight of Austrian skating aficionados who had waited over ten years for one of their countrymen to reclaim the top spot on the World podium, Viennese engineer Fritz Kachler was unanimously first in figures. It didn't hurt that Germany's Werner Rittberger - the odds-on favourite entering the competition - struggled on his forward paragraph loop.

The February 23, 1912 issue of the "Reichspost" offered one of few accounts of the performances in the men's free skate. The newspaper recalled that Kachler "managed everything in his difficult program", that Arthur Cumming "is like his [role] model [Henning] Grenander, a complete acrobat on the ice], that Andor Szende "skated his way through a difficult program safely, but was less beautiful" and that Rooth "skated a very difficult program at a brisk pace."

The results of the men's free skating were all over the place. French judge Louis Magnus (who placed Sweden's Harald Rooth first) and British judge Herbert Ramon Yglesias (who placed Germany's Werner Rittberger first) were the only two judges not to tie at least two skaters for the lead in the free skating segment. Rittberger earned five first place ordinals, Rooth four, Hungary's Andor Szende and Austria's Fritz Kachler two apiece. In an era where nationalistic judging biases were the norm, none of the three British judges placed Great Britain's sole entry, 1908 Olympic Silver Medallist Arthur Cumming, any higher than fifth overall. When the marks were tallied up and the ordinals combined with the scores and factors, Kachler's sizable lead in the figures held up and he easily won his first World title ahead of Rittberger, Szende, Rooth, Cumming and Dunbar Poole, an Australian living in England and representing the Stockholms Allmanna Skridskoklubb in Sweden.

Ludovika and Walter Jakobsson, who'd won the 1911 World Championships by default in Vienna the previous year, faced considerable competition from no less than seven other pairs teams in Manchester... also a record number of entries at that point in time. The event proved to be an extremely close contest. One of the two British judges and the Swiss judge voted for Phyllis and James Johnson, the Hungarian and German judges for the Jakobsson's and the second British judge for Norwegians Alexia and Yngvar Bryn.

Only one and a half ordinal placements separated first and second but the Johnson's managed to squeak out a win in their home country and defeat the reigning World Champions. Bryn's took bronze, ahead of Germany's Hedwig and Hugo Winzer, France's Anita del Monte and Louis Magnus and three British teams who were clearly out of their element. It's interesting to note that Magnus judged both the men's event in Manchester and women's event in Davos but took the ice to be judged by his peers in the pairs event... not an uncommon practice back in those days.

When Fritz Kachler returned to Vienna, he was met at the railway station by well-wishers from the Cottage Eislauf Verein and fêted at an evening reception at his home club's hall. Less than five years later, the Manchester Ice Palace was temporarily closed and used to manufacture observation balloons during The Great War... and less than two months after the Bryn's won Norway's first medal in pairs skating at the World Championships, Wilhelm and Selma Henie welcomed their daughter Sonja to the world.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.

In 1952, Herbert G. Clarke recalled, "In those days it was not considered necessary to skate the compulsory figures on clean ice. The whole rink was open to the public until about 10:30 AM when a few chairs were placed on the ice to mark the space reserved for the Championship figures, and a few skaters, of which I was one, were asked to patrol the ice to see that the competitors were not obstructed by other skaters. I have never seen this happen since."

Zsófia Méray-Horváth

In the absence of Lili Kronberger who had won the event the previous four years, the favourite was Transylvanian born Zsófia Méray-Horváth, who had finished second to Kronberger the previous year in Vienna. However, for the first time since Madge Syers' retirement from the sport in 1908, British skaters had arrived to give the Continental women a run for their money. Méray-Horváth decisively won the school figures with first place marks from four of the five judges. British judge John Keiller Greig stood alone in placing the three British women competing - Dorothy Greenhough Smith, Gwendolyn Lycett and Phyllis (Squire) Johnson - ahead of the reigning World Silver Medallist. In the free skate, Méray-Horváth built upon what was already a firm lead. One of the two Swiss judges and Greig tied her for first with Greenhough Smith and the second Swiss judge gave the nod to Johnson but first place ordinals from the French and Austrian judges assured her a winning placement in both the free skate and overall. Greenhough Smith settled for silver, ahead of Johnson, Lycett, Germany's Grete Strasilla, Austria's Mizzi Wellenreiter and German born Ludovika (Eilers) Jakobsson. In conjunction with the event, an international competition for junior skaters was held in Davos with British skater Basil Williams (representing St. Moritz) taking top honours ahead of six other skaters hailing from Germany, Great Britain and France. There was also a waltzing contest, won by Daphne Wrinch and Herr H. Jensen. Arthur Cumming and Lady Cadogan were second; Gwendolyn Lycett and Louis Magnus third.

Competitors in the 1912 World Championships. Back: Fritz Kachler, Andor Szende, Basil Williams, Arthur Cumming, Ernest Worsley, Yngvar Bryn, Dunbar Poole, Harald Rooth. Front: Muriel Harrison, Mrs. Arthur Cadogan, Louise Lovett, Alexia Bryn. On ice: Werner Rittberger.

On February 16 and 17, 1912, the newly constructed Manchester Ice Palace in England played host to the World Championships in men's and pairs skating. Though unable to attend, Irving Brokaw of New York received an invitation to participate. This invitation marked the first time an American skater was offered a chance to compete at the World Championships and was significant in that at the time, the U.S. wasn't even a member of the ISU. Brokaw's invitation was likely based on his strong ties to Switzerland and his advocacy in bringing the Continental (or International) Style to America.

Judges at the 1912 World Championships in Manchester. Photo courtesy British Ice Skating.

To the delight of Austrian skating aficionados who had waited over ten years for one of their countrymen to reclaim the top spot on the World podium, Viennese engineer Fritz Kachler was unanimously first in figures. It didn't hurt that Germany's Werner Rittberger - the odds-on favourite entering the competition - struggled on his forward paragraph loop.

Fritz Kachler and Werner Rittberger

The February 23, 1912 issue of the "Reichspost" offered one of few accounts of the performances in the men's free skate. The newspaper recalled that Kachler "managed everything in his difficult program", that Arthur Cumming "is like his [role] model [Henning] Grenander, a complete acrobat on the ice], that Andor Szende "skated his way through a difficult program safely, but was less beautiful" and that Rooth "skated a very difficult program at a brisk pace."

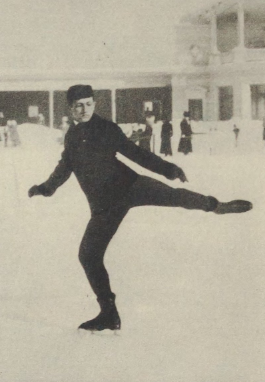

Andor Szende

The results of the men's free skating were all over the place. French judge Louis Magnus (who placed Sweden's Harald Rooth first) and British judge Herbert Ramon Yglesias (who placed Germany's Werner Rittberger first) were the only two judges not to tie at least two skaters for the lead in the free skating segment. Rittberger earned five first place ordinals, Rooth four, Hungary's Andor Szende and Austria's Fritz Kachler two apiece. In an era where nationalistic judging biases were the norm, none of the three British judges placed Great Britain's sole entry, 1908 Olympic Silver Medallist Arthur Cumming, any higher than fifth overall. When the marks were tallied up and the ordinals combined with the scores and factors, Kachler's sizable lead in the figures held up and he easily won his first World title ahead of Rittberger, Szende, Rooth, Cumming and Dunbar Poole, an Australian living in England and representing the Stockholms Allmanna Skridskoklubb in Sweden.

The Manchester Ice Palace

Phyllis and James Johnson practicing in Davos

Only one and a half ordinal placements separated first and second but the Johnson's managed to squeak out a win in their home country and defeat the reigning World Champions. Bryn's took bronze, ahead of Germany's Hedwig and Hugo Winzer, France's Anita del Monte and Louis Magnus and three British teams who were clearly out of their element. It's interesting to note that Magnus judged both the men's event in Manchester and women's event in Davos but took the ice to be judged by his peers in the pairs event... not an uncommon practice back in those days.

When Fritz Kachler returned to Vienna, he was met at the railway station by well-wishers from the Cottage Eislauf Verein and fêted at an evening reception at his home club's hall. Less than five years later, the Manchester Ice Palace was temporarily closed and used to manufacture observation balloons during The Great War... and less than two months after the Bryn's won Norway's first medal in pairs skating at the World Championships, Wilhelm and Selma Henie welcomed their daughter Sonja to the world.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.