Photo courtesy Densho Digital Repository, Nippu Jiji Photograph Archive, Japanese Collection. Used for educational purposes under license permissions.

Born October 30, 1911 in a small town in the Higashitonami District, Toyama, Kazuyoshi Oimatsu was adopted as an infant by the Nakamura family and raised in Osaka. He was exposed to skating as a young boy but did not start taking the sport seriously until his second year of junior high school when a friend invited him to join him for an afternoon of skating, suggesting it might be a pleasant distraction from their studies. Kazuyoshi soon fell in love with the sport.

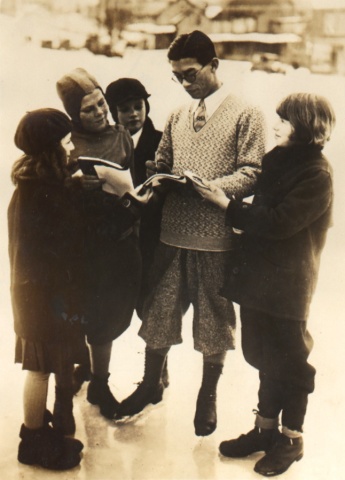

Ryoichi Obitani and Kazuyoshi Oimatsu at the 1932 Winter Olympic Games in Lake Placid. Photo courtesy "Skating" magazine.

Self-taught, Kazuyoshi learned much of what he knew from copying fellow skaters and studying the diagrams of school figures in a book penned by none other than Olympic Gold Medallist Nikolay Panin-Kolomenkin himself. After five years of practice on a relatively tiny rink, he entered his first Japanese Championships at the Kanaya Hotel in Nikko in 1930 and placed fifth. The next year at the moat in Goshikinuma, Sendai City, he returned to the Japanese Championships and won gold ahead of Ryuichi Obitani and Susumu Kobayashi.

In 1932, twenty year old Kazuyoshi and his friendly rival Ryoichi Obitani became the first two Japanese skaters in history to compete at the Olympics when they travelled to Lake Placid, New York to compete in the 1932 Winter Olympic Games. He placed ninth of the twelve skaters competing with sixty seven places and 1978.6 points to Obitani's seventy nine places and 1856.7 points. All but the Austrian and American judges favoured his free skating over at least one of the three American entries who placed ahead of him. In 1980, he recalled, "As I remember now, Lake Placid was surrounded by the Adirondack mountains and with the woods and lakes it was a very beautiful village. The quietness and its high altitude made it a very comfortable place to live in. The people there were kind to us foreigners. A talkative barber, a kindly schoolm'am whose school we attended to learn English, the family of Allen Cottage who offered very cordial hospitalities to us sojourners. A string of pleasant memories comes up one after another as I remember those old days. I have momentos of the old Lake Placid of 1932 which I have kept tenderly for the past forty-seven years."

Photo courtesy Densho Digital Repository, Nippu Jiji Photograph Archive, Japanese Collection. Used for educational purposes under license permissions.

Following the Olympics, Kazuyoshi headed north to compete in the 1932 World Championships in Montreal, where he placed seventh of the nine entries, again making history as one of the first two Japanese skaters to compete in an ISU Championship. It's important to consider that both skaters were competing in North America during a period of growing anti-Japanese sentiments, largely stoked by reported atrocities during Japan's invasion of China. It's impossible to know if these sentiments (or racism for that matter) may have played a role in the skater's reception and marks. It was a different time.

In a letter to "Skating" magazine, Kazuyoshi remarked, "The Olympic Games were really fine. I wish you could imagine how we felt when we arrived at Lake Placid, started training, and saw for the first time the champion skaters. We saw Gillis Grafström, the young Karl Schäfer, and we noticed the beautiful form of Sonja Henie. It made us feel as if we were at the bottom of a valley, and we were very sad. We could see the course we must steer to reach the heights and this inspired us to look forward to the time when we will have overcome all obstacles and can meet skaters from other nations on a level... I think our attending these Games will have a deep meaning, for I am sure that in a few years our skating will improve and compare favourably with that of other countries."

Competitors at the 1932 Winter Olympic Games. From left to right: Roger Turner, Walter Langer, Bud Wilson, Karl Schäfer, Ernst Baier, Gail Borden II, James Lester Madden, Gillis Grafström, Marcus Nikkanen, Ryoichi Obitani, Kazuyoshi Oimatsu and William Nagle. Photo courtesy "Skating Through The Years".

In a letter to "Skating" magazine, Kazuyoshi remarked, "The Olympic Games were really fine. I wish you could imagine how we felt when we arrived at Lake Placid, started training, and saw for the first time the champion skaters. We saw Gillis Grafström, the young Karl Schäfer, and we noticed the beautiful form of Sonja Henie. It made us feel as if we were at the bottom of a valley, and we were very sad. We could see the course we must steer to reach the heights and this inspired us to look forward to the time when we will have overcome all obstacles and can meet skaters from other nations on a level... I think our attending these Games will have a deep meaning, for I am sure that in a few years our skating will improve and compare favourably with that of other countries."

Photo courtesy Densho Digital Repository, Nippu Jiji Photograph Archive, Japanese Collection. Used for educational purposes under license permissions.

After winning the silver medal at the 1933 Japanese Championships and the bronze in the 1935 Japanese Championships, Kazuyoshi headed to Europe. As non-European skaters were then permitted to compete in the European Championships, he entered the 1936 European Championships in Berlin that preceded the 1936 Winter Olympic Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. He placed ninth of fifteen entries in Berlin, but the event was the highlight of his career. Had it not been for a dismal showing in the school figures, he would have been in medal contention based on his free skating performance. The British and Czechoslovakian judges actually had him third in this segment of the competition and the Polish judge joined them in placing him ahead of bronze medallist Ernst Baier... in Hitler's Germany.

The 1936 Japanese Olympic figure skating team. Photo courtesy National Archives Of Poland.

At the 1936 Winter Olympic Games, Kazuyoshi became the first Japanese skater (speed or figure) in history to act as his country's flag bearer. Buried in a deep field, he placed a dismal twentieth overall at those Games, though Finnish judge Walter Jakobsson had him eleventh in free skating. In his final international effort, the 1936 World Championships in Paris, he placed fifteenth of seventeen skaters, but he was the second highest of the four Japanese men entered. Former French Champion Louis Barbey placed him in a tie for tenth in the free skate, ahead of Americans Robin Lee and Erle Reiter.

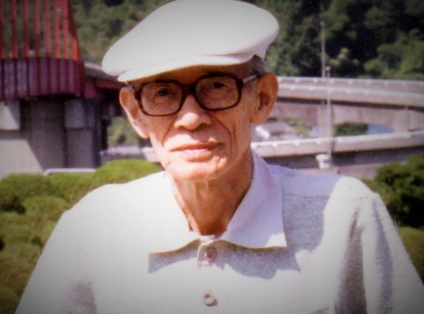

After the War, Kazuyoshi suffered from a bout of tuberculosis and spent several years recuperating. When he recovered, he was invited to coach skating to women and children in Osaka, a career he continued for decades. Kazuyoshi passed away on March 24, 2001 at the age of eighty-nine. The gentle skater's hobbies included writing haiku, classical music, photography and painting. Though he never achieved great success internationally, this forgotten skater from Osaka's role in figure skating history is a fascinating one indeed.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.