"Let us hope that the art of skating may continue its progress in popular favour, and never sigh for new worlds to conquer." - Marvin R. Clark

Born in January of 1840, Marvin Richardson Clark was the only child of Benjamin and Margaret (Gorge) Clark. His father was a provision merchant and his mother was widely known as 'Mother' Clark for her religious work with female inmates in The Tombs and in the Five Points quarter, a dangerous and disease-ridden slum in lower Manhattan, and with the temperance movement. The Clark family shared a home with a grocer and his large family. Though well-known, they certainly weren't well-to-do.

Marvin attended the Mechanics' Institute school, where he edited a school newspaper that he wrote by hand called "Young America". When he graduated in 1856, he won first prize in composition among three hundred and fifty competitors, receiving his prize from William Cullen Bryant, the editor of the "New-York Evening Post".

Marvin then began working for a newspaper, and by the age of twenty-three he was on the staff of the "New York Sunday Dispatch". He grew up to be well-known journalist and editor at several Brooklyn and New York papers, including "Truth", "The Morning Journal" and "The Commercial Advertiser". Though by no means a wealthy man, he was socially connected. Through his connections, he learned about Beekman Pond.

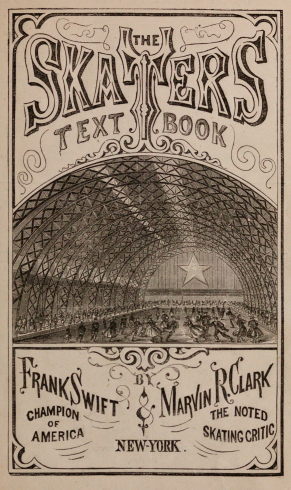

Though there's no evidence to suggest that Marvin was a great skater - or even an especially good one - he became enamoured with 'fancy skating'. He rubbed shoulders with the city's skating elite at the time - Jackson Haines, E.B. Cook, Callie C. Curtis, William H. Bishop (a.k.a. Frank Swift), and countless others. After thoroughly studying the art, he penned "The Skaters Textbook" with Bishop in 1868, which was one of the first true American textbooks on skating ever written. Clark and Bishop's book covered everything from the technical aspects of performing figures to style, skating poetry and history. They even devised a 'revitalizing tonic' specifically for skaters.

Though there's no evidence to suggest that Marvin was a great skater - or even an especially good one - he became enamoured with 'fancy skating'. He rubbed shoulders with the city's skating elite at the time - Jackson Haines, E.B. Cook, Callie C. Curtis, William H. Bishop (a.k.a. Frank Swift), and countless others. After thoroughly studying the art, he penned "The Skaters Textbook" with Bishop in 1868, which was one of the first true American textbooks on skating ever written. Clark and Bishop's book covered everything from the technical aspects of performing figures to style, skating poetry and history. They even devised a 'revitalizing tonic' specifically for skaters.

During Marvin's lifetime, the skating ponds of New York were a sea of humanity. A common issue was the fact that whenever a skater tried to practice figure skating, they were swarmed by throngs of looky-loos. The large groups caused a safety issue, as the ice could easily crack under their weight. They also crowded the figure skaters, making it difficult for them to practice their 'grapevines' in peace. The police would often intervene by telling the figure skaters to stop "making a spectacle of themselves", rather than dispersing the crowds. Marvin was extremely vocal on this injustice in his columns. He once remarked, "The question seems to resolve into this: Have good skaters any rights at all on the ponds? Certainly not, as they have been regulated this far. If they may have, in the future, it must be by the granting of such a simple favor as the reservation of a small portion of the ice where all good skaters, irrespective of organizations, may skate in peace, and where ladies may be protected from the insolence of men or the obscene epithets of ragamuffins."

When he wasn't busy churning out articles about skating, he was busy serving as the Archivist of The Thirteen Club, a group formed to debunk the superstition that if thirteen people were seated together at a table, one would die within the year. Members of the club met on the thirteenth of every month for dinner... with thirteen people seated at each table. On the thirteenth birthday of the club, Clark's successor J.R. Abarbanell recalled, "Marvin R. Clark devoted himself with a tireless energy that knew neither relaxation nor intermission... It is safe to affirm that no single individual in this country, perhaps in the entire world, has delved and digged into the broad field of superstition with greater pertinacity and unending patience and industry than has Marvin R. Clark... It was due to this fact, perhaps, more than any other, that in his last annual report... he was able to state that the Club had reached its full complement of 1300 members - the limit of its membership."

Though Marvin's professional life was rewarding, his personal life was full of tragedy. His wife Lizzie passed away just four years after they married. In 1888, Marvin lost his eyesight. Eliza Archard Conner recalled, "It was working under the gaslight that did it, writing night after night, year after year, in the cruel, yellow, spluttering glare. His sight drew dim very gradually at first. Then he began to use glasses. But the light became dimmer and dimmer somehow... Then the light went out altogether. My friend was blind, stone blind. He couldn't even tell daylight from dark."

Marvin continued to write for a time, hiring a boy to read all of the newspapers to him so he could keep abreast of the daily news. He also learned how to use a typewriter by touch. During this time, he boarded with a German piano tuner, his wife and four children and even spent some time in Bermuda. He earned the moniker 'the blind journalist'. A lover of cats, he penned a book called "Pussy and Her Language" in 1895 which seeked "to prove that the cat has a language of her own" and gave "many cat words with their meanings".

Eliza Archard Conner offered this picture of Marvin during this period: "One familiar with the neighbourhood of Park row, in New York City, will see at times a fine looking, well-dressed man, accompanied by a bright eyed boy attendant, making his way cautiously across the crowded streets. There is an unutterable pathos in his face and the look of resignation that is born only of terrible suffering. Whether one knows the man or not, he will turn to look again at the haunting face with its dark, sightless eyes. But no melancholy appears in the manner or talk of the blind author. He is as cheerful as the golden throated canary that pours its music on the air of his sunny, south windowed room in Brooklyn. And when people ask him, as they often do, 'How can you always be so serene and hopeful always?' he answers: 'Oh well, one must be a philosopher, you know.'"

Sadly, by the autumn of 1893, "nervous disorders had incapacitated him" and Marvin was unable to continue writing to support himself. The "New York Athletic Club Journal" claimed that he suffered from locomotor ataxia, a progressive disease of the central nervous system caused by syphilis. He became an inmate at the Home For Incurables in the Bronx, known later as St. Barnabas Hospital, and relied on a fund collected from his friends at The Thirteen Club and money raised at a series of charity fundraisers to support his treatment. The "New York Athletic Club Journal" noted, "Mr. Clark is a marvel of cheerfulness and philosophy, and to those who know him is as much a wonder as the much talked of Helen Keller."

Marvin, 'the last survivor' of The Thirteen Club's first dinner on January 13, 1882, passed away in obscurity in the first decade of the twentieth century, his contributions to both the literary and skating worlds all but forgotten.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.

.pdf.jpg)