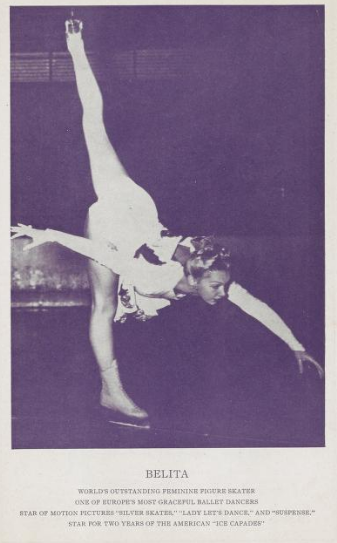

"I believe that Belita is a greater skater than any other woman in the world." - John H. Harris

The tales of those versatile, eclectic souls who are adept in flowing from world to world seamlessly and making an impact wherever they tread are perhaps the most fascinating. Without a doubt, Belita Jepson-Turner was one of those Renaissance people.

Raised wanting for nothing in a historic manor house in Hampshire, England, Belita was thrust into the spotlight by a domineering stage mother. When she danced with Anton Dolin, audiences had no notion of her skill as a skater or an actress. Film noir critics have largely played down her omnicompetence, painting her as an aloof, untrained knockoff of Sonja Henie. The result oriented figure skating world has revered her theatrical presence on the ice but largely relegated her to obscurity because she didn't win a medal at the World Championships or Olympic Games. In all three of these worlds, she was at times an outsider and at times a headliner. Yet no matter how bright Belita's light shined, in whatever world she twirled she eventually became a footnote.

I have endeavoured to include as many quotes from Belita and the central figures in her life as possible to allow them to narrate the story in their own words. In addition to countless interviews, a forty five minute audio recording called "Belita Speaks" is quoted from at length, allowing you, the reader, to gain valuable insight into her own perspective and life experiences. The prologue, a lengthy typewritten partial memoir penned by Belita about her early childhood, offers an intimate juxtaposition to the first chapter.

I would like to offer my sincerest gratitude to Bill Unwin and Elaine Hooper for their extremely generous assistance with this project. I also have to extend huge thanks to Randy Gardner, the late Bob Turk, Charles Rogers, Jean Scott Brennan, Frazer Ormondroyd, Allison Manley, Robin Cousins, Bernard Ford, Cathy Steele, Karina Whiley, Anthony Whitaker, Lynda Young, Anthony Jepson-Turner, Christina Bayliss and Emma McDermott of Theatre Royal Bath and countless others who have contributed and assisted during the research process for this project.

In my thorough research of Belita's life, I found myself relating to many parts of her story. Whether your interest in her life comes through the lens of skating, theatre, film or dance, I hope that you come to appreciate as I did her unique journey through life. I believe you will agree when you finish reading that Belita was a force of nature. Immensely talented, dedicated, blunt, funny and at times chilly, she grabbed life by the horns and savoured it voraciously.

Garlogs Manor, Nether Wallop, Hampshire, 2016. Photo courtesy Elaine Hooper.

PROLOGUE

By Belita Jepson-Turner

She was a lady. She wore pearls, tweeds and low heeled shoes. Her hair was dark brown and long, worn with a center parting then brought down in two thick soft waves on each side of her face and tied into a chignon at the nape of her neck. She was quite beautiful, her body was magnificent, tall and slightly boyish. This woman was lucky; she had money, position, friends, a good-looking husband and three children, two boys and a girl. They lived in a mansion called Garlogs standing in its own park and woods, surrounded by two hundred acres of farmland bordering Salisbury Plains in Hampshire. With the house and land went all the luxuries of county life in the early nineteen-hundreds.

Queenie Jepson-Turner. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

One wonders why this woman was not satisfied. How with her tremendous strength and vitality she could turn her life into one of emptiness and loneliness. Maybe country life was too quiet; possibly she needed more excitement. As a girl her one wish was to be a dancer. When she told her father of her ambition he forbade it, as the stage was taboo for young ladies of high society in that era. With the birth of the daughter she decided that at last her early ambition could be satisfied. One wonders at what exact second the subconscious thought that she would be able to live through this child crossed her mind. I sometimes felt that she had planned my entire life before I was conceived.

Belita's birth certificate. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

I was born October 21, 1923, a few minutes before midnight at Garlogs, the youngest of the three children. Christened in the village church, like all our family have been for generations and where we are all buried. The graveyard is full of us.

The Jepson-Turner burial plot at Nether Wallop Cemetery. Photo courtesy Elaine Hooper.

My name is Belita Gladys Lyne Jepson-Turner. The 'Belita' comes from the diminutive of 'Isabel' in Spanish which is 'Isabelita'. My great grandfather went to and built all the first railways in the Argentine. He married an Isabel there, then named a station and an estancia after her. To keep from getting his wife and the properties confused he called the station and estancia 'La Belita'. Since then there has always been a 'Belita' in the family. Gladys was one of my mother's names. The Lyne is from my Grandfather on Mother's side and comes from Lion. It seems that one of our ancestors was 'Richard The Lion-Hearted'. 'Richard' must have done some strange things in Italy whilst on his Crusades. Grandfather's name was 'Lyne-Stivens' and 'Stivens' is the Anglicized version of 'Stefano'.

Belita in her pram. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

All of the above history is hearsay as I have never troubled to check any of it. The station and estancia do exist as they were mine until Peron took them to give to Eva. From the photographs of the estancia and house that I have seen they look lovely. Someday I hope to go to the Argentine and see it all. Granny was born in Buenos Aires and used to tell me stories about the country, Great Grandfather and the railways.

My brothers, Billy and Dick, are called Bertram William after Grandfather and Daddy; Richard Lyne after King Richard and Grandfather.

Photo courtesy Elaine Hooper

Belita's parents' 1917 marriage announcement. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

'Bumbo' as she called her husband, I have no idea why, really only liked shooting and hunting. Daddy even carried his gun to church on Sundays in case he saw vermin that he could kill on the way. He did not dare take the gun in during a service so he would prop it up in the portal before entering. I remember seeing the gun and thinking how odd it looked standing there.

Queenie, Belita, Dick and Billy at Garlogs. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

Daddy was selfish, cruel, boorish and utterly self-centred. From the time that I was born to his death seven years later he never did a stroke of work, he did not even play the market. I have no idea what he did or how he lived before my birth. He was unbelievably strong, not a large man but beautifully built. His hair was dark and he sported a small military moustache. From top to toe, he was the epitome of the Landed Gentry.

Daddy did not believe in doctors. Once when I was about three years old, he had a toothache. With Billy, Dick and I watching him he tied one end of a piece of string around the tooth, the other to the heavy front door, and ordered one of us to slam it shut. We refused, even though we were longing to see what would happen. Mummy then came into the hall and was furious with 'Bumbo', telling him not to be stupid and to go to a dentist. Daddy flatly refused and with no further ado slammed the door himself, extracting the tooth and spewing blood all over the flag stones. Dick could not stand the sight of blood and was promptly sick. I didn't mind at all. To my amazement I discovered that a tooth, like a tree, has long roots.

Billy and Dick Jepson-Turner. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

The Spanish and German ladies came and went... rather rapidly... as Daddy persisted in insulting them publicly. "Dirty Hun!", "Lying Dago!", "Frog!" Germaine just used to smile, Mummy became angry, everyone else looked rather surprised.

Family photo on the lake at Garlogs. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

Daddy disliked the way Mummy was educating us; he wanted us to go to the village school so that we would stay at Garlogs. His plans for our future were quite simple. Billy was to be the game-keeper, Dick the head-gardener and I the dairy-maid. Mummy of course disagreed with his ideas and the opposing opinions were the foundation for endless violent arguments and fights.

The idea behind the governesses was that we were to have a lesson a day from each of the, and speak little or no English. In fact my 'natural' language at that time was French. This horrified Daddy; he was getting a 'Frog' for a daughter!

Queenie, Billy and Dick. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

We avoided the lessons as often as we could and spent our days running wild over the estate. There were six farms that Dick and I loved to visit. We were forbidden to go near them, but of course we did, the reason being that either one or both of us got hurt each time we went. Mummy was magnificent when bad accidents occurred, she never panicked, she was always calm and reassuring.

Belita playing nurse. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

At this time we children still lived on the top floor of the house with the governesses. Our floor was entirely self-sufficient except for food which came from the kitchens downstairs. Billy and Dick slept

in one room, I was in the night nursery next door; the governesses had separate bedrooms down the landing opposite the schoolroom. Facing south at one end of the landing was a large window in front of which stood an old dining-room table. The walls on each side were lined with bookcases. The rest of the landing was covered with a switchback, a ping pong table, a slide, an electric train, three pedal cars, a tricycle and scooter, a rocking horse, several Meccano sets (which Billy and Dick told me I was too young to touch) and my doll's house. The doll's house was made for me by the village carpenter and looked a little like Garlogs. It had three floors and an attic. At that age, I could get into the rooms if I scrunched up a bit. I spent a lot of time furnishing and cleaning it. It was a nice house.

Belita's doll house. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

The stairwell on our floor was enclosed with wire to prevent us from climbing up the bannisters and plunging headfirst to the bottom. The stairs had a gate across them. We rarely used the front staircase, it was much nicer to use the back stairs behind the baize door. These led, by way of the servants passage, to the stable courtyard, then past the garages and under the arch with the old clock, to the stables and dairy, past these up some stone stairs to freedom. Miles of fields and woods with no grown ups.

Belita at the age of five. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

My days started at about six AM. I used to get out of my bed and crawl into Billy's, then he would read to me "Bulldog Drummond" or "The Saint". Then breakfast and if the weather was good out; if it was bad we stayed on our landing having lessons.

If we were out at lunch time we did not always come home. None of us were good eaters. One of Mummy's biggest problems was to stop the governesses taking food away from us as a form of punishment. We ate as little as possible and we all had loud-voiced objections to certain things. I would eat nothing with lumps in it; if mashed potatoes were given me and I found a lump in my mouth, I was promptly sick.

Billy and Dick Jepson-Turner. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

After lunch was rest time. I used to lie down with Dick and he would read to me. Sometimes his favourite, "Doctor Doolittle", or the "Tarzan" series. Then out or to lessons again till tea time.

When we had finished our tea we did hand work: leather and metal work, all forms of painting including material, glass and china. During this we were read to. What, and in what language, depending on the nationality of the governess on duty. Mommy was very strict about bed time. It was seven thirty, lights out and no nonsense. She used to come upstairs and make sure that we stopped hand work in time to be given our baths so that we would not be late, then she returned to kiss us good night.

Belita, Billy and Dick. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

Billy and Dick were both very good looking but completely different both physically and mentally. Billy's idea of a good time was to go out with the game keeper for the day. Shooting, fishing, ferreting. They used to spend hours checking on pheasants and partridge nests. He really enjoyed learning about all game animals and their habits more than anything else. Dick's idea of a perfect day was quite different. He liked to ride, climb trees, look at things and daydream. He spent hours on the farms with the farmers learning the care of domestic animals.

Photo courtesy Elaine Hooper

At about this point in our lives we were each given a suitable and expensive hobby. It was not considered necessary that we like our hobby, but it was considered essential that it be fragile, delicate and valuable. Something very difficult for young hands to handle and manipulate. Also that it trained the eye for colour, texture and form.

For Billy: birds eggs, and all the tools that went with it.

For Dick: stamps and all the necessary historical ledgerdemain.

For me: China baskets and ornaments.

When I was born my collection of objets d'arts was started. My trousseau was given me at my christening. Brussels lace for the wedding veil and train. Enough lace for all my nightdresses, tea gowns and all the other furbelows needed for a virgin marriage. Instead of toys, people were asked to always give me a piece of china as a present. My job, starting as soon as I could, with reasonable safety, handle delicate and breakable things, was to wash the collection two or three times a year. It numbered some odd fifty pieces even then!

With the arrival of the hobbies came the start (certainly for me) of Mummy's Dream: dancing classes. All three of us were sent to Romsey, about fifteen miles away to have our lesson. Mme. Vacani, who has taught every royal, titled and high society child its first step for years, had started a branch of her school at Romsey. So, to Billy, Dick's and my horror, our dancing career was started.

Belita, Billy and Dick. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

Once a week we were made to dress in party clothes. The two boys in white flannel shorts, white silk shirts, Eaton ties and belts; I in white muslin with embroidered forget-me-not's and mashing sash. Clutching our dancing shoes we were taken to Mme. Vacani's school. The class consisted of ring-around-the-rosy, to waltz time; standing in a line, pointing one foot after the other, then taking a step to the left and curtseys for the ladies, bows for the gentlemen, to a foxtrot; from the corner of the room, arms above the head as though holding a balloon, rising upon the toes, walk daintily across the room, this last was done is various arpeggios! The three of us managed to create havoc with all these exercises and any others the poor misguided teacher tried to teach the undisciplined Jepson-Turner children.

One day returning in the car, sex reared its ugly head. I heard my brothers say how very pretty they found one of the little girls in class. How lovely were her blue eyes and long blonde curly hair!

I was heart-broken and mortified, I was the ugly duckling of the family. I felt that I had lost my brothers love. My hair was mouse coloured, short and straight. Mummy, to my humiliation, always had it put in curl papers every night. Of course, Billy and Dick had curly hair! My skin was the colour of chalk, my eyebrows and lashes blonde so the eyes were invisible, I was undersized and frankly... hideous! Having listened to Billy and Dick rave about this blonde, I was sure that not only had I lost their love, but that no one would ever love me, and I proceeded to howl.

Belita, Billy and Dick skating at Garlogs. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

The next innovation in our lives to upset our freedom was the advent of a pair of boots and skates each. The ice skates were attached to the boots but the roller skates were not. In the winter we were taken to the nearest ice rink, which happened to be in Southampton. Then, the ice skates removed from the boots and replaced with roller skates for the summer. Daddy went with us to roller skate, he was quite good good, not only could he manage to stand up on those extraordinary things but turn around and do a wobbly waltz.

Belita and Billy skating at Garlogs. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

Now our weeks at Garlogs consisted of: in the winter, ice skating, languages, hand-work and playing on our landing; in the summer: dancing, roller skating, languages and running wild over our estate.

Mummy then had another idea, "LONDON".

She did not think we were progressing fast enough along her chosen line, so she decided that London was the answer, where teachers were always more easily obtainable. Whenever any of the family went to London we always stayed with Granny in her fifteen room flat. It was one of those old Victorian blocks, with high ceilings and large rooms, overlooking Regent's Park and Lord's Cricket Ground. One governess, the personal maid, three children, the chauffeur and Mummy went to 54 North Gate for a few weeks. Mummy never travelled light; somehow she managed to organize all of us plus her luggage, ours and various travelling pillows, rugs and receptacles for car sickness, into and onto the Daimler. Under her careful supervision the chauffeur drove us the seventy-eight miles to the flat. There we were greeted by the hall porter. His name was Clough and he had been at North Gate long before the three of us were born.

The first thing that Mummy did in London was to arrange for us to go to Mme. Vacani three times a week for dancing classes; the next was to get a family membership to the Westminster Ice Club where she took us twice a week. This left the morning and late afternoon for lessons and walks in Regent's Park. The Zoo was within walking distance and we went there a lot, sometimes taking a picnic which was great fun.

Mme. Vacani gave a matinee once a year at the old Scala Theatre. For some unknown reason it is highly respectable for such 'do's, though it stands on Greek St. in Soho. Naturally, for fear of offending their parents, all her pupils were in the matinee, whether talented or not.

Billy, Dick and I had been in a couple prior to our joining the London school. My first attempt, or so I have been told, was as the fairy of the Christmas tree. It was a disaster! Instead of doing any of the steps as taught, I went on stage and ran right off into the wings, after which I apparently got lost. Mme. Vacani, and the governess, who had been left to look after me, could not find me anywhere. I was at last discovered outside the stage door in a dead end street with an audience of slum children. It seems that I had decided it was sad that they could not see the show, and taken it upon myself to do it for them. I was showing them all the lovely, pretty things I had seen in the theatre and doing my best to give them the whole performance, dances and dialogue, with full description of costumes and set. Those children must have been very understanding. It's a wonder I was not stoned!

Program for a 1932 pantomime in Nether Wallop. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

My next attempt on stage was as a 'dance mime', a trio with Billy and Dick: "Once there was a nursemaid walking in Hyde Park when she met a soldier and sailor." Billy was a Royal Guard and Dick a sailor. We were all very small so that our costumes had to be hand-made. I wore a white silk dress with turquoise polka dots, a turquoise cape with hood and matching shoes. The pram was made to match me, white outside, turquoise inside, the doll dressed the same. All chosen by me! Billy and Dick looked wonderful in their miniature uniforms. In the number, the nursemaid is walking through the park, she meets a soldier, they talk and do a dance, then a sailor appears, pushes the soldier aside, talks to the nursemaid and they do a Hornpipe. The nursemaid gets tired of both the soldier and sailor, walks off leaving them standing alone, then they go off together. End of number. End of Billy and Dick's theatrical career. I wasn't that lucky.

At Westminster Ice Rink Mummy used to skate with us. She got us a teacher [Eva Keats] who taught us to do edges, three turns and figure eights. Mummy used to waltz and tenstep during the dance intervals. She did them quite well. It was at Westminster, that early in my life, that I first saw my future trainer. His name was Jacob Gerschwiler. In those days he had few pupils. There was one, his favourite called Cecilia Colledge, known to all as Fatty. She was as round as a small tub with a pudding basin for a head. Her hair parted in the middle and pulled into two short braids that stuck out each side of her face. Gerschwiler said she would be a champion, but to us she did not seem very good. Fatty did not like the younger children and was nasty to us all. She was three or four years older than I was.

I could still not do my own boots up, so I had to go to the ladies skate room and to Number Seven. NUMBER SEVEN! Without him there would have been fewer girls skating for Britain in future championships. He watched over us with the loving care of a mother hen. He mended our boots, screwed on and sharpened our skates; when we had finished practicing he wiped and dried our skates, put Vaseline on them and kept our locker keys. He was divine. A round-faced, big, amiable Swedish-type Cockney, with thinning brown hair and a ruddy complexion. I never knew his name.

Skating was fun, dancing a rather boring waste of time. We were all delighted when Mummy decided it was time to return to Garlogs.

At Garlogs, Granny had her own room. It was very large and for some unknown reason was behind the baize door, near the billiard room on the second floor. It was very definitely her room! Billy, Dick and I were never allowed in there except when invited by Granny herself. Granny was tall, beautiful with snow white hair and a character of steel. Mummy was certainly her mother's daughter.

Whenever Granny came to stay at Garlogs, there was always trouble. She and Daddy did not get on well together. There seemed to be an instinctive antagonism between them. Even to us at our age we could sense the animosity. It was almost tangible like an electric shock. She always wore black or dark amethyst dresses which made her look forbidding. As a child, she frightened me.

Belita and her Granny, circa 1938. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

One night I was being naughty and creeping about the house very late. Granny came swooping down like a bat, catching me by the arm and gauging out a chunk of flesh with her beautifully manicured nails. It hurt and bled. I don't think she meant it but she scared the living daylights out of me.

Granny was patroness of all the village charities so her visits coincided with events such as the show in the village hall, the rummage sale and the church fête. Any family meal became pure hell during these times. The arguments for and against everything were awful. Daddy was always against.

Rummage sales were very busy for Billy, Dick and me. Our landing was cleared of all our toys, and trestle tables put up everywhere. All other available space was taken with large cardboard boxes filled to the brim. Mummy had an arrangement with the shops in London whereby they donated all their damaged and out of date stock to the village sale. This all had to be sorted and priced; then there was the hand work table made by ladies of the county and the three of us over the year. This included a speeded up batch of any plain glass or china painted by us as soon as it was unpacked. We could do this quite easily with oil paint and stencils. The stencils were dressed up a bit with brush strokes. The hand work stall was Billy, Dick's and my responsibility. Our landing was invaded by ladies of the Committee all day. Never ending cups of tea and biscuits were passed around. For a week it was a madhouse. Three days before the sale, vans arrived to cart the stuff to the village, then two days work decorating the hall, setting up the stands and exhibiting the goods. People came from miles away. The sale only lasted one day but it made a great deal of money.

The church fête took place in the garden at Garlogs. For Mummy it must have been a great worry. Owing to the two lakes, the hills, woods and drive, the grounds were rather dangerous. We never got through the afternoon without incidents: some funny, some tragic. Once, very early in my life, Mummy was standing ready to receive at the top of the drive, looking proudly at her three children in their spotless white party clothes, when the guests started arriving. About half an hour later she suddenly noticed that she was missing a child. Her heart must have sunk, as with all the activity God alone knew what Dick was up to. She was not kept in suspense for long. An extremely nasty smell of manure, stale mud and rotten vegetation started to waft across the lawn. It was followed closely by Dick. He was white no longer. It seems that getting a little bored, he decided to experiment on his bicycle. He wanted to know how fast he could cross and recross the planks bridging the drainage canal at the bottom of the kitchen garden by the pigsties. Missing one of the planks. he fell in. It took two gardeners to get him out. Mummy, as though nothing had happened, instructed

A vague, virtually impossible attempt was made during the fête to keep the many children in one area to avoid accidents. One of the lakes had a punt. It was a threepenny round trip ride to the island in the middle. This was decorated in various ways. Sometimes it was a floral display, others a tropical forest. Once we made it into "Robinson Crusoe's Island". That was a great success. Usually the booth and punt were given to one of the (supposedly more responsible) older boys to run, with strict instructions that no unattended children were to be allowed on board. But as the afternoon wore on the cries of "Man overboard!" or rather "Look at Sally! She's fallen in!" increased. I think the total of Sally's and otherwise came to fourteen one afternoon.

Another threepence was paid for the privilege of using our tree house. Since Billy, Dick and I were natural athletes and completely fearless this was a rather dangerous adventure for the uninitiated. Quite a few people either got stuck up there and had to be brought down, or simply fell down.

Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

We had a swing. Not an ordinary swing that you that you just sat on, this one you had to climb a ladder to get onto. A low swing would have been no fun at all so we made the gardeners hang ours about five and a half feet in the air. It hung from the branch of a lovely old tree. When Billy, Dick and I wanted to use it we just climbed in the tree and shimmied down the rope. Actually, once one got the swing going to its full height the view from it was very nice. On the one side, the house, the two lakes, the tennis courts, some of the flower garden and large expanses of lawn. On the other, four fields, the water meadow and one of the farm houses.

On the other side of the oak tree from the swing stood the summer house. This was my personal job. I used to decorate the little house with garland of fresh flowers, put in the chairs and table ready for the fortune teller in the afternoon. She charged two and six a reading, took tips and demanded cups of tea. The archery stand was Billy's domain and Dick's the pony ride. Ample room for accidents in all. Mummy's first aid station, run by The Red Cross, was one of the best attended booths.

In the early days, the village show was a family affair. Even Daddy did something. Granny played the piano and accompanied. The governesses did props, scenery and the curtain if they could not perform. Germaine was great. She was the daughter of an opera singer and frightfully good. Years later she went into the theatre professionally with her own show, along the lines of Ruth Draper. Billy and Dick sang, recited and did sketches. Dick was the comedian of the family. Needless to say, I danced!

In one show, I did a pas de deux with Mummy. It was my first attempt at choreography! Mummy was a rainbow, I was a sunbeam; she wore a multi-coloured chiffon dress and a gold headpiece with ribbons hanging from it. She carried a long rainbow scarf, at the other end of which was me. Dressed in all gold. The ballet was not a success. Actually, I spent most of my time tripping over the bloody scarf!

My second attempt was more ambitious. It was called 'A Vase Of Roses'. Mummy was the full grown rose. Patricia (one of my cousins) and I were the rose buds; Billy and Dick the thorns. I had a prop made to look like a large vase. As the curtain went up, we were all discovered standing in a group within it. The little flowers came to life and the ballet had started. I had a lot of trouble with rehearsals. Billy and Dick would not take them seriously and we had to work from gramophone records as Granny had not arrived from London, so there was no rehearsal pianist. My troubles were added to by not being able to get the stage at the village hall, therefore we had to practice at one end of the drawing room on the parquet floor. That floor! It was more like an ice rink than a floor and Daddy forbade us to use resin. I had my heart set on doing lifts with Billy and Dick in the ballet, but every time I threw myself at them their feet would slip and we landed in a heap. I cried a lot during those rehearsals.

Like the pas de deux, it was not a success. It received more laughter than the stunned silence I had envisioned. I have never choreographed anything for anyone, other than myself, since. At least the theatre was saved that.

It was a mystery to me how Mummy could fool herself hat I had more talent for dancing and theatre than any other child. But she did. I used to hear her say that I was a born dancer! It was quite untrue. I was just average.

At about this time, Mummy decided that we should all go to Switzerland for the Christmas holidays. Daddy, when told, was furious. He did not want to leave Garlogs or the shooting over Christmas. Anyway, he had hated all foreign countries since his experiences in the Boer War. He flatly refused to go. When Mummy told us of the plan for the holidays, we became hysterical with excitement. We were going 'abroad' for the first time in our lives.

Before any arrangements could be made, we had to be put onto Mummy's passport. Germaine and the lady's maid, being French, had theirs and were going with us. Next, Mummy took us to Lillywhites where we were outfitted with ski clothes. Billy, Dick's and mine were exactly alike; we were each given a pair of brownish grey ski trousers with matching jackets and caps, beige cashmere sweaters with dark red and blue binding at the neck. The boy's sweaters had V-necks, mine was square. We were also fitted for our ski and snow boots.

I wanted a pair of beige skating boots - they were in fashion at the time - instead of the horrid brown ones I had, also another dress. I hated the one that I had. It was too brown, a flowered print with scallops at the bottom... hideous! Mummy said no to everything.

Mummy's idea of the chic thing to wear for sports was black. Her skating boots were black and her dress, a fine black wool jersey with a pleated skirt, black hat and gloves. She chose a black gabardine ski suit and boots. Maybe she chose black for these two sports as both have white backgrounds. Anyway, she looked quite lovely.

Skis were not bought, as Mummy had told that it was 'done' to rent them from the hotel ski shop.

I loved my skiing clothes for two reasons: they were like my brothers and I found trousers very comfortable. Skirts always caught on things and got in the way.

At last, all arrangements made, the packing finished, we were on our way. The journey to Switzerland was fascinating and uneventful. A few minor fights, a few minor lost articles. We lost Dick at Dover for a while. He had got in the wrong queue. The Channel boat held endless interesting things to look at. We refused to stay in the private cabin. People had rather a bad time keeping track of the three of us during the crossing. From Calais, we boarded Wagons-Lits for Zürich, there we took the funicular railway up to St. Moritz.

The change at Zürich was rather complicated owing to Mummy's manner of travelling. She had two large trunks and fifteen suitcases for herself, not counting her travelling pillow, rug, dressing case and other odd pieces. Billy, Dick and I had a couple of suitcases and a small trunk apiece. To our joy we had each been given a knapsack. Into these all our treasures were stuffed. Germaine and the maid had their luggage too.

The carriages of a funicular are all alike. It is like a skiers train which stops at every little village along the way. The whole train is made of wood and there are no separate compartments. The carriages are small, and inside, the wood is straw coloured and highly polished. The smell is divine: ski wax, snow, cedar, sausages, chocolate and oranges all mixed together. There is a center aisle, on each side of which stand slotted benches, in sets of two facing into each other. The benches are not upholstered.

It was difficult getting Mummy, her luggage and entourage on board and settled. She had never seen a train of this kind in her life. There was a great deal of screaming for 'Cooks' about the fact that there were no private compartments. It took the poor man a long time to explain that if you wished to get to St. Moritz, this was the one and only way to get there, sleighs notwithstanding.

Eventually we arrived at St. Moritz. The station was tiny, smaller than any I had ever seen. It looked, lit up with its fairy lights and its paint, exactly like the cover of a picture book. One only had to open it to start seeing a dream world. I was very nervous getting off the train in case the dream would shatter. To my delight, there was not a car in sight. Just lovely sleighs and those beautiful horses with their pom-pom's and bells. The bells ring through the mountains and valleys from sunrise to sunset like a winter symphony. They are crisp, clean and clear like snow and ice.

Belita, Billy and Dick skating at Suvretta House. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

We arrived at Suvretta House, our hotel, about five thirty in the afternoon. It had taken three sleighs, each drawn by two horses, to get Mummy and her entourage from the station. We had seen little of St. Moritz on the way as it was fairly dark, but our driver could point out the hotel from quite a distance, as it stands above the village in its own grounds and was lit up. Turning into the drive we were greeted by our first sight of real skiers and tobogganists all returning from their day's outing. The cortège of sleighs pulled up at the porte-cochère and at one the divine smell of a Swiss house and the glowing warmth through the glass inner doors welcomed us.

So I made my entrance into my first hotel. The lobby, halls and passages were enormous. There were double doors to all the rooms, with about a foot and a half between each door. All the windows were double too and there was a fireplace in every room. Then the greatest discovery of all: huge feather beds! The joy of running across the room, jumping as high as you can and landing enfolded in a feather bed, with the smell of whatever soap the Swiss use to do their laundry in, is something I shall never forget.

Ours was a corner suite consisting of three bedrooms and a sitting room. Mummy was alone in one room, Billy, Dick, Germaine and I shared the other two. The maid was up in the guest servant's quarters. The bathroom was enormous with a lavatory up two stairs like a throne on a dias. Mummy travelled with all the indispensables: disinfectant, lavatory paper, face towels, soaps, paper lavatory seat covers and a first aid kit in case of accidents. Before we were allowed near the bathroom the maid was sent to clean it. The bath was huge. I had to have a footstool to get into it.

It was quite late when we got to bed that night. Mummy and Germaine had rather a difficult time getting us to stop our tour of exploration through the hotel.

Next morning, another introduction into one of the joys of life: café au lait, croissants and brioches with mountain honey. Mummy was extremely upset because the waiter had not brought marmalade. Of course, she had already had her morning tea and biscuit in bed, brought by her personal maid.

Billy, Dick and I were overwhelmed with so many new things to look at, eat and touch. Billy and I, we both had rather sensitive stomachs and were beginning to feel slightly sick from excitement but neither of us would admit it. Everything was too wonderful.

The view from the window was breathtaking. The Alps, with the sun slowly rising and the snow reflecting the myriads of colours. From our corner of the hotel, we could see no human activity at that time as the skiers had not yet started their daily workout. The ice rink was on the other side of the hotel. Very vaguely in the distance, the church spire started to be seen.

Having got into our new clothes, we could not wait to get out to see what the snow was like. The first surprise when we got outside was that it did not seem really cold, even that early with the sun not at its height. Later on in the morning we ran around without sweaters. A strange thing happened. We found that after running a little, we became short of breath and a bit dizzy. We dared not mention how we felt to either Mummy or Germaine in case they thought we were ill and kept us in. It was some days before we all found out that the strange feeling was due to the altitude.

Belita, Billy and Dick on the slopes in Switzerland. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

The first thing we made Mummy organize when she came downstairs was the renting of our skis. Another new experience! We were all made to stand with our feet together, arms extended above our heads. If, with the skis standing upright we could palm the points, the skis were the right size. The next thing was to convince Mummy to get us three toboggans. Mummy refused to let us ski until she had reserved an instructor, so shaking with excitement we settled for tobogganing.

Belita skating at Suvretta House. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

I think Mummy was a little frustrated that none of us had shown the slightest interest in the ice rink. We had not even gone to look at it. However, by then it was lunch time so she had to keep quiet about it. We had insisted that the ski instructor be booked early the next morning so the afternoon was free. Mummy got us on ice.

I can't for the life of me remember who she got to teach us that winter. It must have been one of the instructors under contract to Suvretta House. The three of us had progressed to rather wobbly figure eights and threes to a center, We could also go backwards by then. Mummy was rather partial to the dance interval and had a dance instructor to teach her the new dances. One of them was the Ten-Step.

Belita skating at Suvretta House. Video courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

One of the nicer things about a holiday in St. Moritz are the teas as we soon found out. Delicious hot, bitter chocolate with lashings of whipped cream and wonderful cakes. These were served in the lobby of the hotel. Once and a while we went into the village to have tea at Rumplemeyer's, which was in a very old four storied house. It was always terribly crowded.

In a couple of days we had settled down to a daily routine. Skiing in the morning, skating in the afternoon and either ping pong, indoor bowling or games after tea until bedtime. After we had been put to bed, Mummy used to go out, and I presume she enjoyed herself, but I have no clue where, with whom or what she did. She used to change whilst we three had dinner in the sitting room, then come and kiss us good night, looking divine in evening dress wearing jewelry and carrying her furs.

Belita, Dick and Billy skiing in Switzerland. Video courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

Skating one afternoon, Billy was accosted by a very strange girl. She asked him if he wanted to dance with her. None of us could really understand what she wanted. Her speech and voice were very peculiar. Billy was horrified as he did not like girls at this time. Especially ugly ones. And this one really was ugly! They got through a waltz together and he said he was tired. Later at tea, an extraordinary lady beckoned the entire family to her table. Her dress was of sapphire velvet and she wore a black hat sporting a very large jewelled hat pin. Her hands were covered in rings. There must have been one on every finger. She also wore four or five ropes of pearls and on her front a diamond brooch. I was amazed, never having seen jewellery worn in the daytime, except for the traditional single rope of pearls. Her voice and accent were unbelievable. She turned out to be the strange girl's strange mother.

The girl's name was Carolinda and the mother was called Lady Butterfield, how or why I do not know. It appeared that they came from America, a place called Chicago, and that Lady Butterfield had something to do with meat. She told Mummy that she was very, very rich: a millionaire. Carolinda wa her only child and Lady Butterfield wanted her to have young friends to play with. She had noticed how well Mummy organized the daily activity of her brood and would it be alright for Carolinda to join them? Mummy said yes!

Carolinda turned out to be the sort of girl that plays lacrosse, the sporty type! She went at everything like an onrushing tank, including Billy. She had taken a lot of skiing lessons and was very good. Her skating was dreadful. She ploughed on with us every morning, noon and night. Dick and I had a lot of trouble with her. Not only were we younger, but by being around, frustrated her plans with Billy. Poor Billy. He had a miserable time trying to avoid her. I really loathed her. She pushed me around all the time. Once, she shut me up in between the double doors leading from the sitting room to one of the bedrooms and left me there. It was an hour before I was found. The entire hotel had been made to search for me. Mummy was angry.

Lady Butterfield became entranced by her daughter's skating and decided to have a yearly competition and donate a trophy. It was called the Butterfield Cup. I am certain that the idea originated with Mummy. The cup was for young ladies under twelve and was inaugurated at the Palace Hotel Ice Rink. Carolinda did not win.

Sometimes we went to skate at other hotel rinks. It was then that I saw for the first time the great skaters of the world: Karl Schäfer, Ernst Baier, Sonja Henie, Felix Kaspar and the younger batch that were being trained as future champions. This was my first introduction to really good skating and the possibilities of the medium.

There were various trainers always around, many of whom were pointed out to me as Gods. There was, of course, Jacob Gerschwiler, Howard Nicholson (one of Sonja Henie's trainers), Eugen Mikeler and many others. It all looked to me like a lot of work. Billy, Dick and I were not really impressed by skating, but Mummy wished us to get our Bronze medals when we returned to England.

Dick's 'self-portrait' of himself skating. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

Looking back, it seems to me that for the three of us, anything athletic or concerning movement seemed extraordinarily easy. The thing we loved best of all was skiing. That big day came when we were to take our third class tests. Even Mummy went in and passed. Billy and Dick got very good marks and I think that I was just 'allowed' through because I was so small. I could never do the turns properly and was forever falling on my face but, oh, how I loved it!

We arrived at Arosa, had lunch and were told afterwards to go and spend the afternoon much as we wished. Billy and Dick and the older Earle boys took off somewhere. I went with the younger ones to the ice rink where we played around. We were on the ice when Billy suddenly came running down to the rink, looking very frightened with a very white face to tell us that Mummy, on her way down to the rink, had been hit from the back by a tobogganist and had broken her shoulder. It seemed that she'd been taken to hospital where her shoulder was being set.

Quite suddenly, Billy became the head of the family and with the help of Germaine took care of everything. Dick and I were not allowed to go and visit Mummy, but Billy did and came back to tell us that she was alright, but in a great deal of pain. Her orders were that we were to return, quite regardless, to St. Moritz where she would join us the following day. How she managed to join us, how she withstood the pain, is something that I will never know. The organization of getting herself up the mountain minus an ambulance must have been fantastic.

She arrived at the hotel with arm and entire shoulder in a plaster cast. She then informed us that it was very badly set, that she simply could not stay in a foreign hospital and that she simply had to get back to London so that Sir William Willcox - who was our Godfather and student of Grandfather's - could organize the resetting of all the broken bones. With which she started our departure, arranging train tickets, berths, boat cabins, the maids, Germain and us!

Two days later, we were on the boat. We were warned as we boarded the channel boat that it was going to be a rough crossing. We went immediately to the cabin where we stayed till the swells started, then for some unknown reason Dick suddenly started feeling sick. Mummy, Germaine and the three of us went up on deck, Germaine assisting Mummy, where we sat on one of the benches, looking out to sea.

The waves were enormous and the boat was pitching wildly. The sailors kept coming up and asking us to go below. They told us that it was unsafe for us to be on deck. Mummy, in her usual way, explained that one of her children became seasick if enclosed in the cabin and that it was preferable for us to get air. At the end of her speech, the boat took a rather bigger lurch and Billy and I fell right off the bench and ended up practically falling through the railings along the side of the deck. It may sound unbelievable, but the railings were actually far enough apart at that time for a child to slide under the first rung. This rather frightened Mummy, with which she decided it would be better for us in the cabin. We had a rather difficult journey back as Mummy, with the heavy cast, found it very hard to walk and balance and every time she hit a wall, it obviously hurt her very much.

The rest of the journey was fairly quiet. Dick was not sick until nearly the very end of the crossing and I, like a stupid ass, took one look at him and proceeded to follow his lead. It was Billy's turn to laugh as then the maids started and Germaine and so that they only two feeling no pain were Billy and Mummy.

In a rather bedraggled state, we got into the Daimler which had been sent from Garlogs and were driven to London. Mummy was put to bed, Uncle Will was called and we were all told that Mummy's shoulder was not a broken shoulder, but an extremely badly splintered and fractured collarbone running into the neck. Uncle Will said that she should go into a nursing home. Mummy acquiesced and said that she would go in just long enough to have the entire thing cut open, the chips taken out, wired back together again, and made Uncle Will promise that he would let her come home as soon as she was conscious. To my knowledge, she only stayed in for three days. She again returned, this time with a much lighter cast than she had before, and seemed to be in less pain. None of this seemed to deter her from her original plans, which were to return to Garlogs for the hunting season and look after her people.

Garlogs again... It was getting to the point where Billy and Dick's schooling had to be decided.. They had been put down for several schools including preparatory and private, and they were now getting towards the age where a definite decision had to be made. This caused endless arguments between Mummy and Daddy, which I heard as I passed doors and windows during the day. Eventually, Billy and Dick were told they were to go to St. Peter's Court in Broadstairs, meaning that Billy would go a little older and Dick a little younger than usual.

Belita, Billy and Dick. Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

Now, there started to be big changes in Garlogs. It was decided that the boys should move downstairs to sleep. So, a room was prepared next to Mummy and Daddy's suite for Billy and Dick. The room was redecorated: new beds, new furniture and new carpeting. Egg shell walls and a white ceiling overlooking one of the lakes. I was still upstairs with the governesses. Also, another innovation: Billy was allowed down to dinner. It seemed that Dick and I weren't old enough yet. Dick had to wait a few months. I had to wait a few years.

In the meantime, we had all three progressed to breakfast and lunch in the dining room. Our life (three three of us) had changed a little. I now wore the same clothes as my brothers. In other words, I was dressed in brogues, woollen socks, knickerbockers, a shirt and one of my skiing sweaters and my hair was put in a hairnet. From the back, you could not tell us apart. The only distinctive mark I had to prove that I was a girl and not a body was the square neck of my sweater.

Daddy, at this point in my life, started to teach me to be a good country girl. I was sent out with the gamekeeper to learn to handle ferrets and the art of rabbiting, how to pluck, skin and clean game, birds, rabbits and hares. When there was a shoot on, Billy sometimes used to go as a loader, but Dick and I had to go into the beater's cart from which we worked. After we had beaten, we had to go and pick up the game and bring it home where it was divided into so many brace per gun depending on the bag. The rest was taken to a cabin in one of the woods where it was hung either for eating or for sale. Daddy ran Garlogs as a shooting estate and it was one of the best, if not the best in England. Daddy was also probably the best gun in England and Billy was rapidly following in his footsteps.

One morning after breakfast, Daddy told me to come with him to the gun room where he took out a gun and loaded it and told me that I was to learn how to shoot. We walked out of the front door, across the drive and onto one of the lawns where he looked around and obviously decided that we were far too close to everything, so we went on a bit further down the hill towards one of the lakes where there was nothing that could be hurt or injured by a bit of gunshot within range. He then told me for probably the hundredth time in my life how to put a gun to my shoulder, right along the barrel, where the trigger was, how to stand, and anything else that he though necessary such as aim, the difference being that I realized the gun was loaded. He left me, telling me that when he said "Pull!" I was to pull the trigger. I stood there, holding the gun up and finding it just as difficult to keep the barrel steady, owing to the weight of the gun, as I always had when it was unloaded. At his command, I pulled the trigger.

The gun went one way, I went ass-over-tip downhill, ending up near the lake with what I was convinced was a broken shoulder like Mummy's. Daddy's anger at my incompetence, lack of strength and in his opinion, lack of courage, was something to behold. I refused to touch a gun again and would not even go and pick the thing up. I ran up the hill into the house and went screaming to Mummy where she read me the riot act and told Daddy that he was wicked to have given me a gun and asking me to shoot it and that he was never to do such a thing again.

Mummy still rode, sidesaddle, in those days and went hunting with Daddy, who was Master Of Hounds. They must have decided that it was time for us to have a pony. Up until then, we had been riding a dear old thing much too large for us called Moses. He was a sort of grey white, one of the gentlest creatures I've ever known. He used to follow us around like a dog. So, one day to our amazement, a horse van arrived and this very small, compact, muscular wild-eyed Arab pony was led out, and the three of us were told that it was ours and that we were to look after it. Mummy appeared, took one look, turned on Daddy, demanding an explanation of this horse. It seemed that she had wanted a nice, docile, quiet little pony on which it would be safe for us to ride, not a thoroughbred Arab trained for showing. It was very difficult to get the Arab pony into the stable and then into her loose box. Her name was Snowdrop.

Next morning, Billy tried to ride her. She bucked him off. Dick had a go. The same result. An immediate decision was made. I was not allowed near her. Once again, Mummy demanded of Daddy an explanation of where he had found her. His answer was that he had bought her cheap from Lord Bathurst because she had thrown all the Bathurst children. She was a beautiful horse with superb pedigree, with which Daddy went through all the breeding information. Mummy said she did not care what the pony looked like, who it was out of, or where it came from, that for us children it was unrideable and that he was to get rid of it immediately. This was never done. Somehow, Dick calmed her down and in a little while I was allowed to ride her on a guide rein with Salter, the groom, riding Moses.

One afternoon, I was out with Mummy and Salter. Mummy was on her mare. We were going past the back of one of the farm went a tarpaulin blew off one of the plows, frightening the mare, who shied and started to kick and buck. To my horror, I saw Mummy start to slide, saddle and all, under the horse's belly. The girth had not been tied up tight enough. Mummy landed virtually head first into the mud and farm dirt common to all country lanes. I expected her to be very angry and also very frightened. She was neither. Mummy calmly asked Salter to quiet the horse, resaddle her and help her to mount, with which we finished our ride. Mummy told me after we got home and I asked her if she was alright: "But of course, darling! You've never ridden with Bumbo. He goes straight through hedges and trees and it'll kill him one of these days. Next time you're near Daddy's horse, take a look at his mouth and face. They are terribly scarred. I am quite used to it and Bumbo would be very upset if I had not continued the ride in front of Salter." The first lesson: the fear must never be shown either to animals or people.

It was again approaching Christmas. The year had passed with various visits to London. The rummage sales, the fête and the village show. Daddy, it seems, for once had won an argument and we were to stay home for Christmas and go to St. Moritz a few days later.

Photo courtesy Elaine Hooper

There was always an enormous barrel full of Christmas pudding mix by the back door outside the servant's hall. This mix had to be stirred once for luck, once for a wish and from then on every time you passed it, so that the brandy and glazed fruit blended and the entire mixture matured. It was then put up as usual in pudding basins with the silver charms mixed in and tied in cloth. One of these was given to every house in the village and a huge one for us. The tree always arrived about a week and a half before the twenty-fifth. It was a nerve-wracking time because the tree when standing would reach from the ground floor right up to the skylight dome at the top of the house. It was very difficult and complicated to get the tree into the house and then to stand it up through the stairwell. The top of the tree had to be tied to a pulley and it had to be guided into position, some branches cut and wires attached to different parts of the trunk to keep it in position. The bottom of the tree was placed in an enormous tub of earth. Daddy had rather a thing about this. He always tried to keep some roots of the tree alive so that it could be replanted.

The whole procedure took about two days. We then started to decorate. This was a traditional thing at Garlogs: every branch and twig had to have the finest layer of cotton wool on it. The lights were put on by the gardeners, then the fairy on top of the Christmas tree, and all white decorations down halfway to the first landing, from then on all pastel colours, deepening down to the dark colours at the bottom of the tree. If there were not enough garlands or if some had been smashed the year before, we had to make others. The last thing to go on the tree was the tinsel.

Then there were the hundreds of presents to be checked to make sure they had no price tags on them, then wrapped and labelled. There was never less than one present for every servant and farmer and farm family on the estate. The dining room table was moved to one end and trestle tables brought in for the buffet tea, as the villagers and everyone came for the afternoon.

Mummy made Christmas stockings for us and all the house guests and servants in the house. They were not the small stockings which we see today, but full length ladies cotton stockings, dyed red. These she used to make up herself with the help of the governesses on Christmas Eve, and one put in everyone's bedroom.

Somehow, Mummy always looked tired on Christmas Day. When I found out about the stockings, I realized why. Granny always came to us for Christmas. When it was over, there was always a great feeling of relief, owing to the tension caused by the disorganization of the house and everyone's lives for the month and a half of preparation.

The family, minus Daddy (as usual) went to Switzerland, returning to London instead of Garlogs that year. Billy, Dick and I were to go in for our Bronze skating medals. I was particularly anxious to pass. Mummy had promised that if I did well, I could have a new skating dress and boots. This was incentive enough for me to work hard over the holidays. It also set the pattern to be followed for many years. We all three passed and got our medals; I won my dress and boots. It was a lovely dress, powder blue velvet with a little hat to match. At least I got my beige boots and a new pair of skates. I was terribly pleased and proud of them but there was one slight difficulty. Mummy insisted on my wearing stockings and she had great trouble getting a corset made to fit with the suspenders to hold them up. The first time that I put on the whole ensemble, she found to her horror that the suspenders showed below my knickers. As she had never attempted to dress a skater, she had no idea what to do.

Eventually, the suspenders were disposed of and the stockings were sewn to ribbons attached to the bottom of the corset. I was also given beige silk gloves. This was to be my one and only skating dress for at least two years.

There was a great deal of bustle and a great many shopping expeditions to outfit Billy and Dick for their prep school. Maybe it was the fact that I was on my own for the first time, both skating and dancing, I don't know. Anyway, I told Mummy that Mme. Vacani was of no use to me anymore and that I should go to a school called The Cone School for my dancing. I think I must have been told or have heard about this school from one of the teachers at Mme. Vacani's. I could certainly not have heard it from any of the pupils. It was not a society school. In fact, it was not just a dancing school but an educational school as well. The regular students had all forms of normal educational subjects and took their regular exams. Plus that, they had dancing, music and acting.

I was beginning to think as an individual. My idea, of course, was that I should be enrolled as a regular student. However, this ambition was quickly stopped. I won part of the fight and was permitted to go as a private pupil for all forms of dancing, acrobatics and musical interpretation. I suppose that the desire to go to the school really started because of the fear of having absolutely no one to play with when Billy and Dick left. I was dreading their leaving home. I, in a way, wanted to go too. When all their school things had been bought and their little trunks and suitcases (and an attaché case each) were delivered to the flat, I stood in the hall and cried. We all then went back to Garlogs for a final few weeks before they left.

It was mushroom time and so we used to get up very early before breakfast to pick the mushrooms out of the fields to bring them back and have them cooked in milk and butter and then to gorge ourselves. The trouble was that all through the southern counties as far as mushrooms were concerned, the early bird definitely catches the worm. One day we were out all climbing a fence as usual and I was following Billy and Dick. I got stuck on some barbed wire. They paid no attention to me and just continued walking. In my efforts to get unhooked, I ran one of the barbs into the back of my leg and was stuck there. Nobody came for me for about two to three hours. It never entered Billy or Dick's mind to look for me until someone asked after breakfast where I was! As neither of my brothers had the faintest idea, it took some time to find me. I still have a rather nasty scar on the back of my leg.

These last few weeks at Garlogs with Billy and Dick were wonderful, even though there was a feeling of excitement about their new life. Sometimes, the boys were frightened; sometimes they were happy and pleased. The three of us at that time were very close. Mummy and Daddy fought a lot about this issue. Daddy did not want the boys to go to St. Peter's Court but Mummy was adamant. Finally, the day came for us to all go to London in order for them to catch the school train from Waterloo Station. We left Garlogs very early in the morning. Daddy came with us and went to the North Gate for an early lunch before going to the station. I could feel my tummy beginning to ache but I was determined to say nothing.

I think it must have been the autumn term as it's the shortest and because I was still wearing my white summer clothes. After lunch, we all got in the car rather sombrely and drove across the Thames to the station. Halfway across the bridge, the line of cars filled with little boys and their parents started and I could feel the tension mounting inside Billy and Dick. It took quite a while before we pulled up and could get the car unloaded and start walking towards the platform. I know I felt ice cold. Mummy was being very gay, Daddy sullen, Granny organized. Billy and Dick looked white and I think they must have been very apprehensive. The platform was crowded. One could see that everyone was near tears but that nobody was going to give way. There were special carriages with signs in the windows saying 'St. Peter's Court, Broadstairs'. Billy and Dick found seats then came back to the platform. We hung about for what to to me seemed like hours. Finally, the whistle blew. I could see that Dick was near tears. Billy, by now, was just grim. They got on the train and it started to pull out of the station. I felt dizzy and fainted. It was to me the end of my life.

Granny, Daddy, Mummy and I returned to North Gate where Daddy took the car straight to Garlogs. Mummy and I stayed with Granny at the flat. It was all horrid. It was so empty and lonely. I was given breakfast in my room, lunch and tea in the dining room, dinner in my room. My room was slowly being transformed into a school room. Eventually, the bed was take out and I slept in a little guest room. I think that Mummy, having got the boys off to school, was taking this time to sort out my future education. She had arranged for me to become a private pupil at The Cone School for an hour a day in the afternoons. She had also found an English teacher, Kathleen Murphy. Through Kathleen - with whom she got along very well - she must have found all my future academic teachers. Through The Cone School, the piano and singing teachers. My life, while all this sorting out was going on, was very lonely.

Like all lonely children, I escaped into the servant's hall which was warm, cozy and jolly. The cook's name was Mabel. She was absolutely bright, plump, blonde hair, blue eyed and larky. Eva, the parlour maid, was the epitome of all parlour maids: tall, thin, brown hair, brown eyed and severe in every way. Once in a while, she was kindly. The scullery maids and maids were all 'dailies' so they came and went. Mabel would let me help once in a while. I pushed fruit through sieves to make an English dessert called 'fool' and was allowed to roll out the pastry for tarts. Sometimes, I was sent for the afternoon to visit a distant cousin, Patricia Beresford, who lived in a large house on Avenue Road a few streets away. She was a drip. She always wore frills. She had a nanny.

I had all new clothes, which I found very uncomfortable as since the first time in Switzerland I had taken to wearing Billy and Dick's hand-me-down clothes, all except the sweaters, which were my old skiing ones. My hair had always been in a net and from the back you couldn't tell me from the boys. The only dresses I had were party dresses. Now, Mummy was dressing me in silk shantung with a double coloured smocking yoke and matching shantung knickers. She also took me to Anelo & Davide where my shoes were especially made of the finest kind of colours to match the smocking on my dresses, the reason for the shoes being that Mummy had found out through a doctor's daughter that children's feet were easily damaged by wearing stiff shoes.

The only bit of excitement to take place in these weeks was Jeanne Earle. It was to be her coming out dance. She was seventeen and at Cheltenham, the only other girl in the family, my first cousin. Her hair had to be put up by hairdressers in the flat. There were dress makers for her dress. Everyone had something to say about the colour and design for her first evening dress. Primrose yellow chiffon was eventually decided upon. There was a great to-do on the night of her coming out party. Granny gave Jeanne her grown-up pearls, Mummy gave her a brooch and Auntie Marie gave a bracelet. We started to dress her about three o'clock in the afternoon. There was a terrific fuss. I was into everything and very miffed because I was too young to go to the ball. For weeks after, I dreamt about what I would wear and how I would look when I was old enough to 'come out'...

PART ONE

"I am English, of course. Granny is practically Argentine and Italian in descent, granddaddy the same. They met in the Argentine, where granny still has many estancias. Daddy's blood was Spanish and Scotch. I'm sure we all have some French in us, too." - Belita Jepson-Turner

In the picturesque village of Nether Wallop, Hampshire, England, among a sea of old thatched roofs, you will find a sprawling estate dating back to the fourteenth century called Garlogs.

The estate was purchased in the early twentieth century by Dr. Bertram Herbert Lyne-Stivens, who was a throat surgeon of great esteem and a consulting physician to the court of King Edward VII. Dr. Lyne-Stivens had a private practice in Grosvenor Square in London's Mayfair District and was one of the first people in Nether Wallop to own a car. In his Landaulette, he would commute daily to Grately Station to catch a train to London to attend to his patients. In his absence, the daily management of Garlogs was left in the care of a staff of no less than twenty two servants: a butler, a footman, two housemaids, one between maid, one lady's maid, one governess, one cook/housekeeper, one kitchen maid, two chauffeurs, three stable lads, one carpenter, one bricklayer, four gardeners and two gamekeepers. Farm labourers were also employed and the grand estate played host to the Annual Show of the Wallop Horticultural and Floral Society.

Isabelita Jemima Drabble

Dr. Lyne-Stivens' wife was Isabelita (Belita) Jemima Drabble, the only daughter of George Wilkinson Drabble. George was the son of one Charles Drabble, who travelled to Argentina by sailing ship in the nineteenth century and played an important role in the English colonization of Buenos Aires. He opened his own bank in the city, established five large cattle ranches to export frozen mutton from Argentina to England with his River Plate Fresh Meat Company and built railroads on the Central Argentine Railway to his properties. One of the terminal railroad stations was called 'La Belita'.

George Wilkinson Drabble

When Dr. Lyne-Stivens, the great throat surgeon somewhat ironically passed away of a throat infection in May of 1915 (two years after his daughter Elsie Maie, who tragically died at the age of thirteen), Garlogs was acquired by Major William Jepson-Turner, a military man who had served in the Boer War. Jepson-Turner was courting Dr. Lyne-Stivens' daughter Gladys, known to friends simply as Queenie. The Major and Queenie married in December of 1917 and transformed the opulent manor house with its twenty bedrooms into a family home. First came two sons, Bertram William (Billy) and Richard Lyne (Dick), and then, on October 21, 1923, the protagonist of our story, Belita Gladys Lyne Jepson-Turner was born.

As Belita explained in the prologue, the Jepson-Turner children were educated privately and raised in affluence. As a founding member of the committee of the Royal Academy Of Dancing, Queenie had a great appreciation of the arts. Her own thwarted dreams of becoming a successful dancer and skater shaped her determination to introduce her daughter to both dance and skating lessons at an early age.

Belita felt that Queenie was "just lucky that I had some facility for movement and line and that my eye could catch movement and line. Also, I was quite loose." As for skating, Belita believed that her Mummy "had some idea that the movement of ice and the speed going forwards and backwards and the spins would help me in my ballet. I must admit she turned out to be quite right about that." Queenie also briefly subjected Belita to piano lessons at the Royal Academy Of Music. She became quite proficient. In one competition, she was in the same class as Eileen Joyce and even beat the daughter of the great Myra Hess. This early exposure to music gave Belita a firm understanding of how to interpret it from an early age.

Belita skating at the Eisstadion in St. Moritz, circa 1935. Video courtesy courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

As was fashionable for many British families of means at the time, the Jepson-Turner's wintered in St. Moritz, Switzerland. By the age of eight, Belita won the Butterfield Challenge Cup for 'excellence and beauty in figure skating'. This competition for skaters under the age of fourteen was organized by Lady Hilda Butterfield, the wife of Sir Frederick Butterfield of the baronial Cliff Castle at Keighly, Yorkshire. In winning, Belita defeated Lady Butterfield's own daughter Carolinda Waters Fischer. She repeated that win two years later. In her diary from January 1934, Olympic Bronze Medallist figure skater Maribel Vinson recalled, "One day last week, they held a special contest for children under fourteen, and about eight entered. They decided to run it on ideal lines just to see if anything like a uniform result is possible. So they invited the champion of Belgium (Yvonne de Ligne), the champion of Germany (Ernst Baier), the champion of England (Megan Taylor), a Swiss skater, and the champion of the United States (Guess Who) to act as the panel of judges. Then just to finish up with a complete flourish, the vice-president of the International Skating Union (Dr. [Herbert J.] Clarke) acted as referee while one of the popular young members of the London Ice Club (Tony, no less) was the starter. Some of the kids didn't know an inner from an outer edge to begin with, and to be judged by so many champions completely removed whatever ability they had, but they were all cute as could be and one or two were so funny that the sedate judges couldn't keep straight faces to save them. There was one boy, an Italian, and he fought hard, but three girls had his measure, and the first two real talent. No. 1, Belita Jepson-Turner, an English child with a full repertoire of jumps, spins and stagy spirals was a complete mistress of theatricality even to a change of costume in between school figures and free-skating, all at the age of ten! Another ten-year-old, Susie Delvol, was second, a German less who was less accomplished but skated in a more quiet, pleasing style; I shouldn't wonder a bit if both are future champions. And to prove the point of all this, all five judges agreed on every place for every competitor, except the two lowest. Perhaps when Senior international championship judges know as much or more than the competitors, uniform judging blanks will be the result." By the age of ten and a half, Belita both earned the silver and gold medals of the National Skating Association.

Weaving seamlessly from the ice to the dance floor, Belita passed her all of her dance exams by the age of nine. "That included the Royal Academy Of Dancing, British style, the Cecchetti, Greek, acrobatic, tap and character," she recalled, adding that, "strangely enough, the Russian ballet style was not done in England at all at that time, and I really didn't start working with Russian teachers until I was about thirteen, I think." Too young to apply for the Cecchetti School, Adeline Genée offered to teach her. Genée was President of the Royal Academy Of Dancing in London until she was succeeded by Margot Fonteyn when she retired in 1954 and was regarded highly in dancing circles, but ultimately Belita caught the eye of another great in the ballet world.

Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

Photo courtesy The Jepson-Turner Private Family Collection. Used with permission.

Laws in England at the time which were geared largely towards regulating theatrical and circus performances prohibited paid professional appearances by children under the age of fourteen. As such, Belita was not paid for giving numerous appearances while touring Great Britain with Dolin as his young dance partner. That most certainly did not stop her from making an impression. "He refused to have me on the road as a child," explained Belita. "I was fully dressed as a grown-up with the make-up, the jewels, the bag and the hat and the whole lot. I must have looked really very, very, very silly." Overdressed or not, she quickly adapted to the extremely foreign world of touring with support from older dancers. "Two of the ballerinas, who were in their late teens, decided to help me out and show me the ropes of touring," explained Belita. "One of them is the now Lady Menuhin, who was then Diana Gould... We had a wonderful time and they couldn't have been nicer to me and they couldn't have been better teachers. My first recollection of touring was washing my teeth on the first morning and there was one tap in the hall in 'the digs', which was what the English people called a theatrical rooming house, and I had eight people in front of me waiting to get to the one tap. I was really very shocked as I was a terribly spoiled child." While touring with Dolin, she played at Blackpool, where she dined with circus sideshow performers from the resort town's fairgrounds and "skated in any town where there was an ice rink, but not very seriously."

Laws in England at the time which were geared largely towards regulating theatrical and circus performances prohibited paid professional appearances by children under the age of fourteen. As such, Belita was not paid for giving numerous appearances while touring Great Britain with Dolin as his young dance partner. That most certainly did not stop her from making an impression. "He refused to have me on the road as a child," explained Belita. "I was fully dressed as a grown-up with the make-up, the jewels, the bag and the hat and the whole lot. I must have looked really very, very, very silly." Overdressed or not, she quickly adapted to the extremely foreign world of touring with support from older dancers. "Two of the ballerinas, who were in their late teens, decided to help me out and show me the ropes of touring," explained Belita. "One of them is the now Lady Menuhin, who was then Diana Gould... We had a wonderful time and they couldn't have been nicer to me and they couldn't have been better teachers. My first recollection of touring was washing my teeth on the first morning and there was one tap in the hall in 'the digs', which was what the English people called a theatrical rooming house, and I had eight people in front of me waiting to get to the one tap. I was really very shocked as I was a terribly spoiled child." While touring with Dolin, she played at Blackpool, where she dined with circus sideshow performers from the resort town's fairgrounds and "skated in any town where there was an ice rink, but not very seriously."

Belita and Anton Dolin. Photo courtesy Bill Unwin.