When you dig through skating history, you never know what you will unearth. In the spirit of cataloguing fascinating tales from skating history, #Unearthed is a once a month 'special occasion' on Skate Guard where fascinating writings by others that are of interest to skating history duff are excavated, dusted off and shared for your reading pleasure. From forgotten fiction to long lost interviews to tales that have never been shared publicly, each #Unearthed is a fascinating journey through time.

Mary Anne Barker's life cannot have been easy. Born in Spanish Town, Jamaica in 1831, she was widowed in her early thirties and forced to leave two children in England when she remarried and moved to New Zealand. While living halfway across the world, a third child died in infancy and her farm failed. Returning to England, she became a prolific journalist and author, writing everything from poetry to cookbooks. Later in life, her husband's work saw her living in Africa, Australia and The Caribbean.

An interesting and overlooked footnote in her compelling life story is the fact that she in fact wrote a widely read account of ice skating in New Zealand... in the nineteenth century. Published in her 1873 book "Station Amusements In New Zealand", her memoir "Skating In The Back Country" referred to the popularity of summer ice skating on Lake Ida in Canterbury, New Zealand. It is unique, charming and speaks to a passion for skating as a pastime in a time and place that we so little get to read about. Now in the public domain, I am sharing Barker's lengthy account below in its entirety.

SKATING IN THE BACK COUNTRY (MARY ANNE BARKER)

Mary Anne Barker

I think I have mentioned before that the wooden houses in New Zealand, especially those roughly put together up-country, are by no means weather tight. Disagreeable as this may be, it is doubtless the reason of the extraordinary immunity from colds and coughs which we hill-dwellers enjoyed. Living between walls formed by inch-boards overlapping each other, and which can only be made to resemble English rooms by being canvassed and papered inside, the pure fresh air finds its way in on all sides. hot room in winter is an impossibility, in spite of drawn curtains and blazing fires, therefore, the risk of sudden changes of temperature is avoided.

Some such theory as this is absolutely necessary to account for the wonderfully good health enjoyed.

by all, in the most capricious and trying climate have ever come across. When strong nor’-wester.

was howling down the glen, have seen the pictures on my drawing-room walls blowing out to an angle of 45°, although every door and window in the little low wooden structure had been carefully

closed for hours. It has happened to me more than once, on getting up in the morning, to find

my clothes, which had been laid on chair beneath my bedroom window overnight, completely covered by powdered snow, drifting in through the ill fitting casement. This same window was within

couple of feet of my bed, and between me and it was neither curtain nor shelter of any sort. Of

winter's evening have often been obliged to wrap myself up in big Scotch maud, as sat, dressed

in high linsey gown, by blazing fire, so hard was the frost outside; but by ten o'clock next

morning would be loitering about the verandah, basking in the sunshine, and watching the light

flecks of cloud-wreaths and veils floating against an Italian-blue sky. Yet such is the inherent dis

content of the human heart, that instead of rejoicing in this lovely mid-day sunshine, we actually

mourned over the vanished ice which at daylight had been found, by much-envied early riser,

strong enough to slide on for half an hour. It seemed almost impossible to believe that any one

had been sliding that morning within few feet of where sat working in blaze of sunshine, with

my pretty grey and pink Australian parrot pluming itself on the branch of silver wattle close by, and

'Joey,' the tiny monkey from Panama, sitting on the skirt of my gown, with piece of its folds

arranged by himself shawl-wise over his glossy black shoulders. If either of these tropical pets had been left out after four o’clock that sunny day, they would have been frozen to death before our supper

time.

It was just on such day as this, and in just such bright mid-day hour, that distant neighbour of ours rode up to the garden gate, leading pack horse. Outside the saddle-bags, with which this animal was somewhat heavily laden, could be plainly seen beautiful new pair of Oxford skates, glinting in the sunshine; and it must have been the sight of these beloved implements which called forth the half-envious remark from one of the gentlemen, "I suppose you have lots of skating up at your place?" "Well, not exactly at my station, but there is a capital lake ten miles from my house where am sure of good day's skating any time between June and August," answered Mr. C. H——, our newly

arrived guest.

We all looked at each other. believe heaved deep sigh, and dropped my thimble, which 'Joey' instantly seized, and with low chirrup of intense delight, commenced to poke down between the boards of the verandah. It was too bad of us to give such broad hints by looks if not by words. Poor Mr. C. H—— was bachelor in those days: he had not been at his little out-of-the-way homestead for some weeks, and was ignorant of its resources in the way of firing (always an important matter at station), or even of tea and mutton. He had no woman-servant, and was totally unprepared for an incursion of skaters; and yet, —New Zealand fashion, no sooner did he perceive that we were all longing and pining for some skating, than he invited us all most cordially to go up to his back-country run the very next day, with him, and skate as long as we liked. This was indeed a delightful prospect, the more especially as it happened to be only Monday, which gave us plenty of time to be back again by Sunday, for our weekly service. We made it rule never to be away from home on that day, lest any of our distant congregation should ride their twenty miles or so across country and find us absent.

When the host is willing and the guests eager, it does not take long to arrange plan; so the next

morning found three of us, besides Mr. C. H——, mounted and ready to start directly after breakfast.

have often been asked how managed in those days about toilette arrangements, when it was impossible to carry any luggage except small "swag," closely packed in waterproof case and fastened on the same side as the saddle-pocket. First of all must assure my lady readers that prided myself on turning out as neat and natty as possible at the end of the journey, and yet rode not only in my every-day linsey gown, which could be made long or short at pleasure, but in my crinoline. This was artfully looped up on the right side and tied by ribbon, in such way that when came out ready dressed to mount, no one in the world could have guessed that had on any cage beneath my short riding habit with loose tweed jacket over the body of the dress. Within the "swag" was stowed brush and comb, collar, cuffs and handkerchiefs, little necessary linen, pair of shoes, and perhaps ribbon for my hair if meant to be

very smart. On this occasion we all found that our skates occupied terribly large proportion both of

weight and space in our modest kits, but still we were much too happy to grumble.

Where could you find a gayer quartette than started at an easy canter up the valley that fresh

bracing morning? From the very first our faces were turned to the south-west, and before us rose

the magnificent chain of the Southern Alps, with their bold snowy peaks standing out in glorious

dazzle against the cobalt sky. stranger, or colonially speaking, “new chum,” would have thought we must needs cross that barrier-range before we could penetrate any distance into the back country, but we knew of long winding vallies and gullies running up between the giant slopes, which would lead us, almost without our knowing how high we had climbed, up to the elevated but sheltered plateau among the back country ranges where Mr. C. H——'s homestead stood. There was only one steep saddle to be crossed, and that lay between us and Rockwood, six miles off. It was the worst part of the journey for the horses, so we had easy consciences in dismounting and waiting an hour when we reached that most charming and hospitable of houses. had just time for one turn round the beautiful garden, where the flowers and shrubs of old England grew side by side with the wild and lovely blossoms of our new island home, when the expected coo-eee rang out shrill and clear from the rose-covered porch.

It was but little past mid day when we made our second start, and set seriously to work over fifteen miles of fairly good galloping ground. This distance brought us well up to the foot of high range, and the last six miles of the journey had to be accomplished in single file, and with great care and discretion, for the track led through bleak desolate vallies, round the shoulder of abutting spurs, through swamps, and up and down rocky staircases. Mr. C. H–— and his cob both knew the way well however, and my bay mare Helen had the cleverest legs and the wisest as well as prettiest head of her race. If left to herself she seldom made mistake, and the few tumbles she and ever had together, took place only when she found herself obliged to go my way instead of her own. We entered the gorges of the high mountains between us and the west, and soon lost the sun; even the brief winter twilight faded away more swiftly than usual amid those dark defiles; and it was pitch dark, though only five o'clock, when we heard sudden and welcome clamour of dog voices.

These deep-mouthed tones invariably constitute the first notes of sheep-station's welcome; and

delightful sound it is to the belated and bewildered traveller, for besides guiding his horse to the right

spot, the noise serves to bring out some one to see who the traveller may be. On this occasion we

heard one man say to the other, "It’s the boss:" so almost before we had time to dismount from our

tired horses (remember they had each carried heavy "swag" besides their riders), lights gleamed

from the windows of the little house, and wood fire sparkled and sputtered on the open hearth. Mr.

C. H–– only just guided me to the door of the sitting-room, making an apology and injunction to

gether, — "It’s very rough am afraid; but you can do what you like;"—before he hastened back to

assist his guests in settling their horses comfortably for the night. Labour used to be so dear and

wages so high, especially in the back country of New Zealand, that the couple of men - one for indoor work, to saw wood, milk, cook, sweep, wash, etc. and the other to act as gardener, groom, ploughman, and do all the numerous odd jobs about a place a hundred miles and more from the nearest shop, represented wage-expenditure of at least £200 year. Every gentleman therefore as matter of course sees to his own horse when he arrives unexpectedly at station, and I knew I should have at least half an hour to myself.

The first thing to do was to let down my crinoline, for I could only walk like a crab in it when

it was fastened up for riding, kilt up my linsey gown, take off my hat and jacket, and set to work.

The curtains must be drawn close, and the chairs moved out from their symmetrical positions against

the wall; then made an expedition into the kitchen, and won the heart of the stalwart cook, who

was already frying chops over the fire, by saying in my best German, "I have come to help you with

the tea." Poor man! it was very unfair, for Mr. C. H—— had told me during our ride that his

servitor was German, and had employed the last long hour of the journey in rubbing up my exceedingly rusty knowledge of that language, and arranging one or two effective sentences. Poor Karl's surprise and delight knew no bounds, and he burst forth into long monologue, to which I could find no readier answers than smiles and nods, hiding my inability to follow up my brilliant beginning under the pretence of being very busy. By the time the gentlemen had stabled and fed the horses and were ready, Karl and between us had arranged bright cosy little apartment with capital tea-dinner on

the table. After this meal there were pipes and toddy, and as I could not retire, like Mrs. Micawber

at David Copperfield's supper party, into the adjoining bed-room and sit by myself in the cold,

made the best of the somewhat dense clouds of smoke with which was soon surrounded, and

listened to the fragmentary plans for the next day. Then we all separated for the night, and in two

minutes was fast asleep in little room no bigger than the cabin of ship, with an opossum rug on

sofa for my bed and bedding.

It was cold enough the next morning, I assure you: so cold that it was difficult to believe the

statement that all the gentlemen had been down at daybreak to bathe in the great lake which spread

like an inland sea before the bay-window of the little sitting-room. This lake, the largest of the

mountain chain, never freezes, on account partly of its great depth, and also because of its sunny aspect. Our destination lay far inland, and if we meant to have good long day's skating we must start at once. Such perfect day as it was! I felt half inclined to beg off the first day on the ice, and to

spend my morning wandering along the rata-fringed shores of Lake Coleridge, with its glorious enclosing of hills which might fairly be called mountains; but feared to seem capricious or lazy, when really my only difficulty was in selecting pleasure. The sun had climbed well over the high barriers which lay eastwards, and was shining brightly down through the quivering blue ether overhead; the frost sparkled on every broad flax-blade or slender tussock-spine, as if the silver side of earth were turned outwards that winter morning.

No sooner had we mounted (with no "swag" except our skates this time) than Mr. C. H - set

spurs to his horse, and bounded over the slip-rail of the paddock before Karl could get it down. We

were too primitive for gates in those parts: they only belonged to the civilization nearer Christchurch;

and had much ado to prevent my pony from following his lead, especially as the other gentlemen

were only too delighted to get rid of some of their high spirits by jump. However Karl got the top

rail down for me, and “Mouse” hopped over the lower one gaily, overtaking the leader of the ex

pedition in very few strides. We could not keep up our rapid pace long, for the ground became

terribly broken and cut up by swamps, quicksands, blind creeks, and all sorts of snares and pit-falls.

Every moment added to the desolate grandeur of the scene. Bleak hills rose up on either hand, with

still bleaker and higher peaks appearing beyond them again. An awful silence, unbroken by the

familiar cheerful sound of the sheep calling to each other - for even the hardy merino cannot live in

these ranges during the winter months, It brooded around us, and the dark mass of splendid "bush,"

extending over many hundred acres, only added to the lonely grandeur of the scene. We rode almost

the whole time in deep cold shade, for between us and the warm sun-rays were such lofty mountains that it was only for few brief noontide moments he could peep over their steep sides.

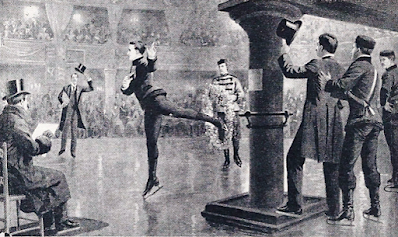

General view of Lake Ida, with skaters on the ice. New Zealand Free Lance : Photographic prints and negatives. Ref: PAColl-8602-04. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. Used with permission.

After two hours' riding, at the best pace which we could keep up through these terrible gorges,

sharp turn of the track brought us full in view of our destination. can never forget that first glimpse

of Lake Ida. In the cleft of huge, gaunt, barehill, divided as if by giant hand, by large black

sheet of ice. No ray of sunshine ever struck it from autumn until spring, and it seemed impossible

to imagine our venturing to skate merrily in such sombre looking spot. But New Zealand sheep far

mers are not sentimental am afraid. Beyond rapid thought of self-congratulation that such "cold

country" was not on their run, they did not feel affected by its eternal silence and gloom. The ice

would bear, and what more could a skater's heart desire? At the end of the dark tarn, nearest to the

track by which we had approached it, stood neat little hut, and judge of my amazement when, as we

rode up to it, young gentleman, looking as if he was just going out for day's deer-stalking, opened

the low door and came out to greet us. Yes, here was one of those strange anomalies peculiar to the

colonies. young man, fresh from his University, of refined tastes and cultivated intellect, was leading here the life of boor, without companionship or appreciation of any sort. His "mate" seemed to be a rough West countryman, honest and well meaning enough, but utterly unsuited to Mr. K——.

It was the old story, of wild unpractical ideas hastily carried out. Mr. K—— had arrived in New

Zealand couple of years before, with all his worldly wealth, 81,000. Finding this would not

go very far in the purchase of good sheep-run,and hearing some calculations about the profit to

be derived from breeding cattle, based upon somebody's lucky speculation, he eagerly caught at one

of the many offers showered upon unfortunate "new chums," and bought the worst and bleakest

bit of one of the worst and bleakest runs in the province. The remainder of his money was laid out

in purchasing stock; and now he had sat down patiently to await, in his little hut, until such time

as his brilliant expectations would be realized. I may say here they became fainter and fainter year

by year, and at last faded away altogether; leaving him at the end of three lonely, dreadful years with

exactly half his capital, but double his experience.

However, this has nothing to do with my story, except that can never think of our skating expedition to that lonely lake, far back among those terrible hills, without thrill of compassion for the

only living human being who dwelt among them. It was too cold to dawdle about, however, that

day. The frost lay white and hard upon the ground, and we felt that we were cruel in leaving our poor

horses standing to get chilled whilst we amused ourselves. Although my beloved Helen was not

there, having been exchanged for the day in favour of Master Mouse, shaggy pony, whose paces were

as rough as its coat, begged red blanket from Mr. K——, and covered up Helen's stable companion, whose sleek skin spoke of milder temperature than that on Lake Ida’s “gloomy shore.” Our simple arrangements were soon made. Mr. left directions to his mate to prepare repast consisting of tea, bread, and mutton for us, and, each carrying our skates, we made the best of our way across the frozen tussocks to the lake.

Mr. K—— proved an admirable guide over its surface, for he was in the habit during the winter of getting all his firewood out of the opposite "bush," and bringing it across the lake on sledges drawn by bullocks.We accused him of having cut up our ice dreadfully by these means; but he took us to part of the vast expanse where an unbroken field of at least ten acres of ice stretched smoothly before us. Here were no boards marked “DANGEROUS,” nor any intimation of the depth of water beneath. The most timid person could feel no apprehension on ice which seemed more solid than the earth; so

accordingly in few moments we had buckled and strapped on our skates, and were skimming and

gliding - and I must add, falling - in all directions. We were very much out of practice at first, except

Mr. K——, who skated every day, taking shortcuts across the lake to track stray heifer or explore

blind gully.

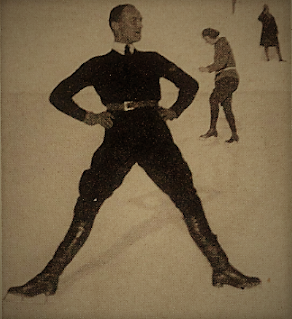

Whites Aviation photograph of skaters on Lake Tekapo circa 1950. Photo courtesy

The National Library Of New Zealand.

I despair of making my readers see the scene as saw it, or of conveying any adequate idea of the intense, the appalling loneliness of the spot. It really seemed to me as if our voices and laughter,

so far from breaking the deep eternal silence, only brought it out into stronger relief. On either hand

rose up, shear from the water's edge, great, barren, shingly mountain; before us loomed dark pine

forest, whose black shadows crept up until they merged in the deep crevasses and fissures of the

Snowy Range. Behind us stretched the winding gullies by which we had climbed to this mountain

tarn, and Mr. K——’s little hut and scrap of garden and paddock gave the one touch of life, or

possibility of life, to this desolate region. In spite of all scenic wet blankets we tried hard to be gay,

and no one but myself would acknowledge that we found the lonely grandeur of our "rink" too much

for us. We skated away perseveringly until we were both tired and hungry, when we returned to

Mr. K——'s hut, took hasty meal, and mounted our chilled steeds. Mr. C. H–– insisted on bringing poor Mr. K—— back with us, though he was somewhat reluctant to come, alleging that a few days spent in the society of his kind made the solitude of his weather-board hut all the more dreary.

The next day and yet the next we returned to our gloomy skating ground, and when I turned round in my saddle as we rode away on Friday evening, for a last look at Lake Ida lying behind us in her winter black numbness, her aspect seemed more forbidding than ever, for only the bare steep hill-sides could be seen; the pine forest and white distant mountains were all blotted and blurred out of sight by a heavy pall of cloud creeping slowly up.

"Let us ride fast," cried Mr. K——, "or we shall have a sou'-wester upon us," so we galloped home as quickly as we could, over ground that I don't really believe could summon courage to walk across, ever so slowly, today - but then one's nerves and courage are in very different order out in New Zealand to the low standard which rules for ladies in England, who "live at home in ease!" Long before we reached home the storm was pelting us: my little jacket was like white board when I took it off, for the sleet and snow had frozen as it fell. was wet to the skin, and so numb with cold could hardly stand when we reached home at last in the dark and down-pour. could only get my things very imperfectly dried, and had to manage as best could, but yet no one even thought of making the inquiry next morning when came out to breakfast, "Have you caught cold?" It would have a seemed ridiculous question.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.