When you dig through skating history, you never know what you will unearth. In the spirit of cataloguing fascinating tales from skating history, #Unearthed is a once a month 'special occasion' on Skate Guard where fascinating writings by others that are of interest to skating history duff are excavated, dusted off and shared for your reading pleasure. From forgotten fiction to long lost interviews to tales that have never been shared publicly, each #Unearthed is a fascinating journey through time. This month's #Unearthed is a fascinating article by the late Gordon Wesley written the autumn after Barbara Wagner and Bob Paul won their first of four World titles. It originally appeared in the October 1957 issue of "Imperial Oil" magazine and has been shared with the permission of the fine folks at Imperial Oil.

"HER FUTURE'S ON ICE" (GORDON WESLEY, SHARED WITH PERMISSION FROM IMPERIAL OIL)

One brisk December day 13 years ago, a well-bundled five-year old took her first faltering steps on her first pair of skates on a Toronto backyard rink.

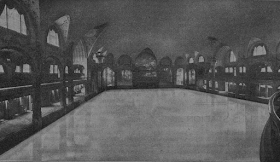

Last February the same girl, now a well-proportioned young woman with shoulder-length blonde hair and a contagious smile, stepped confidently on the ice in Colorado Springs' posh Broadmoor Ice Palace. For five minutes, she and a slim, handsome youth swooped and spun across the slick surface, climaxing their routine with a daring shoulder-high knee-catch. Applause roared from the stands as skating-wise spectators anticipated the judges' decisions - Canadians Barbara Wagner, 18, and Robert Paul, 19, were the new world's champion pairs skaters.

If tears were seen to glisten in Barbara's hazel eyes, there was good reason. The seemingly effortless performance by the two young skaters was the product of thousands of hours of rugged rehearsing. Their easy-looking physical harmony was the result of a regimen that would tax a professional fighter. For six years they had dedicated themselves to skating. For Barbara there had been few parties because there wasn't time, no skiing because she might injure herself, no swimming because it tends to over-relax skating muscles, no sundaes because skaters must watch their weight.

Nor were Barbara and Bob the only ones to have made sacrifices. Barbara's father, James H. Wagner, a senior member of Imperial's public relations department, had shown his faith in his daughters ability by spending thousands of dollars for lessons and equipment. A 15-minute skating lesson costs $3.25. Skates and boots are worth $110 a pair and Barbara wears out a pair in nine months. A two-month stint of summer-skating in Schumacher, Ont. costs him $900 a year.

But Jim, an immensely proud father, shrugs off these expenses. "Our car is three years old," he says with a smile, "and maybe we could spend the money on new furniture. But we prefer it this way. Any parent with a talented child would do as much, and after all, doesn't any other parent do as much, say when he puts his child through medical school?" But what of Barbara? Does she sometimes long to be a normal teen-ager? Has the sacrifice been worth it? If that five-year-old in the Wagner backyard had known what was in store for her, would she have exchanged her skates for a doll-house?

"I would have chosen to skate," says Barbara. "Anything you have to do continuously - like skating or golf or even business, I suppose - you get tired of sometimes. But deep down you have to love it or you wouldn't be able to continue."

And there's another side to it. "Look at all the things my skating has brought me," she points out. "I've crossed the Atlantic twice. I've skated all over North America and travelled all over Europe. I've been entertained in palaces and met all sorts of fascinating people. I have friends all over the world."

Barbara's natural cheerfulness and her keen zest for living have stood her in good stead on her travels. At the 1956 Winter Olympics in Cortina, Italy, her off-ice activities won the hearts of the Italians. Speaking a sort of pidgin Italian, Barbara, dubbed "Leetle Mees Canada" by the Italians, spent her off-hours wandering through the village's picturesque streets, chatting with newsboys about the day's headlines or picking up interesting items about the town's history from the Cortina town clerk. Her energy astounded everyone. In her two weeks in Cortina, she visited every church and historical site within a five-mile radius. The Canadian Press described her as "one of Canada's top goodwill ambassadors."

Oddly enough, neither Barbara or Bob particularly wanted to win the Olympic gold medal that year. They wanted to see another Toronto couple, veterans Frances Dafoe and Norris Bowden, crowned champion. "Franny and Norry are retiring at the end of this year and it will be a shame if they don't win," said Barbara before the competition. As it turned out, the Bowden-Dafoe team lost out to an Austrian entry, [Schwarz] and Oppelt. Barbara and Bob placed sixth, then went to Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, for the world championships and finished fifth - and that was the beginning of their climb to the top.

"We knew 1957 would be their year," said coach Sheldon Galbraith, 34-year-old professional at the Toronto Skating Club. It was indeed their year. All the month of February they won the North American title at Rochester, the Canadian pairs title at Winnipeg and the world pairs title at Colorado Springs.

Now they have their sights fixed on the 1960 Olympics at Squaw Valley, California. For the next two and a half years, they will dedicate their time and energy to preparing for that single five-minute performance that will decide their right to be Olympic champions. At least until they get a chance at the Olympic title, they will remain amateurs. They will defend their various titles and give occasional exhibitions to keep themselves in top condition. After the Olympics - who knows? "Maybe," said Barbara, "if neither of us is married and there are good offers, we'll turn professional." But that's a long way off.

Barbara's story properly begins when she was taken to ballet school at three and a half. With a natural responsiveness to music and her long golden curls, she was an immediate success. But her parents soon decided she had had enough. "I didn't want her to spend her life travelling around as a ballet dancer," says her father. To which Barbara laughs, "Look at me now!"

Discarding her ballet slippers for skates, Barbara taught herself to stay upright in short order. At nine she joined the University Skating Club in Toronto, but soon found that Saturday mornings were not enough. She moved to the Toronto Skating Club and in 1951, without ever had a professional lesson, she won the club championship for girls under 12 years old. The next year she took two junior titles and, with a young lad named Robert Paul, was runner-up in the junior dance competition.

Compared to Barbara, young Bob had got off to a pedestrian start. He had reached the ripe old age of nine when his parents bought him a second-hand pair of figure skates so he could keep up to a young girl cousin. The next year he contracted polio - luckily, a non-paralytic type. While recuperating in hospital, he told his family, "When I get out of here, all I want is a nice new pair of skates." He got his skates.

Meanwhile, Barbara's progress, largely self-taught, was not going unnoticed. Sheldon Galbraith, who had coached Barbara Ann Scott to her World and Olympic titles in 1948, saw her possibilities and convinced her parents she needed professional coaching. She was only 12 years old when Galbraith suggested to her parents that she "summer-skate". The Wagner's balked. Mrs. Wagner argued that Schumacher was about 500 miles north of Toronto and Barbara was still a little girl. Jim Wagner objected - after all, he said, there was more to life than figure skating; she should be playing tennis and swimming and doing all of the other things girls of her age were doing. Barbara broke down all the arguments in typically feminine fashion; showing her usual determination she wept until her parents agreed to at least have a look at Schumacher.

Barbara was a little taken aback by the frontier appearance of the mining town. Still she was pleased with the McIntyre arena with its three artificial ice rinks and other recreational facilities, all built primarily for employees of the McIntyre Porcupine gold mines. Galbraith assured the Wagners that their daughter would be well-chaperoned and cared for and they headed back to Toronto minus their skating daughter.

At first Barbara did nothing but figures and solo skating. But she was short - she's only five feet one inch today - and Galbraith thought it might lengthen her stride and improve her technique to pair her with Bob Paul, who is now six feet and weighs 175 pounds. So well did they perform together he decided to train them as a pair and the following spring - 1954 - they won the Canadian junior pairs title at Calgary. Obviously they were naturals. As Galbraith put it: "Any weakness one might have is corrected by the other. Barbara has the grace and expression and Bob has the muscle power."

In 1955, now seniors, they were runners-up to Dafoe and Bowden in the Canadian Championships held in Toronto. That same year Barbara and Bob ventured into even deeper water, competing in both the North American Championships at Regina and the world meet at Vienna. Not that they had any hope of winning, but their coach deemed it important they gain international experience. So good an impression did they make that they were invited with other Canadian skaters to give exhibitions in Davos, Lausanne and Zürich in Switzerland; Paris, France; and several North American cities.

Psychologically, the youthful stars have now reached a crucial point. "Right now," says Galbraith, "they're going through their worst period. They would like to let up because there's not the same incentive. There are times where there's nothing left but willpower."

Sheldon seldom lets up on their training, driving himself as hard as he drives his pupils. Skating around the pair in lazy circles, he calls out, "Now!" for the timing of a lift, and then, "Feel it now, feel it!" Sometimes he will signal for the music to be stopped, show Barbara how he wants her to do a split mazurka and tell her to try again with the half-serious warning, "Three thousand of those and you'll have it right!"

Even if they wanted to, Barbara and Bob are usually too out of breath for repartee. In a sport which temperament - and temper - is accepted almost as the norm, these two are noted for their serenity. The pair avoid seeing too much of each other of the ice because, as Barbara says with typical good sense, "We've seen too many pairs go down the drain because they let themselves get emotionally attached. Besides, she says, they have different off-the-ice interests.

Barbara has developed a highly effective method of avoiding temper outbursts. When she finds herself becoming angry, she simply turns her back and walks away. "I can't see any point," she says, "in saying something you'll regret later."

Her charm and even disposition have won her friends all over the world. Almost every day letters and requests for photographs arrive from some distant corner of the world, usually from people she has never met. Some are addressed simply, "Miss Barbara Wagner, Champion Figure Skater, Canada". She makes a point of answering all her fan mail and carries on a regular correspondence with two girls in Lausanne, Switzerland. Fame she finds very pleasant. As for the crowds who regularly turn up to watch her skate: "The more the merrier - I love them!"

She admits to one superstition - the number 13. When she started school, she came home with a 13 for her mother to sew inside her coat and she graduated from St. Clement's girls' school last June 13. In most competitions she manages to find a 13 either on a hotel room or a street number. Always on the watch for her lucky number, Barbara was happy when she found out she had been assigned no. 58 in the World Championships in Colorado Springs. "After all," she points out, "eight and five make 13, don't they?"

An avid reader - she prefers modern fiction - Barbara regrets her career allows no time for university. Last year she began a course in fashion design, her favourite hobby, but her skating forced her to drop out. Her skill in dress designing has not been wasted - she usually designs her own skating costumes and her mother sews them, a major economy.

Naturally thrifty, Barbara does her best to hold down expenses. As a world champion, she has most of her travelling costs paid for by the Canadian Figure Skating Association. Earlier trips to competitions, however, were financed by her father. When Barbara competed at the World Championships in Vienna in 1955, her mother went with her as chaperone - and Jim footed the bill. Last year Jim took advantage of a month's holidays to take his wife and 24-year-old son, John, to Italy and Germany to watch Barbara skate. "It was expensive," he smiles, "but worth every cent of it."

As far as the expenses are concerned, Barbara and Bob seem to be over the hump. At a reception for the pair at the Toronto Cricket Skating and Curling Club last March, both were presented with life memberships, to which Barbara reacted with unbridled enthusiasm. "Just think," she bubbled happily, "I'll be able to skate free until I'm 90!"

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.