Photo courtesy "Ebony" magazine

"I have a certain way of being in this world, and I shall not, I shall not be moved from doing what I think is right by jealousy, ignorance or hate." - Maya Angelou

"I do not skate with my feet but with my head." - Mabel Fairbanks, "The Chicago World", June 26, 1948

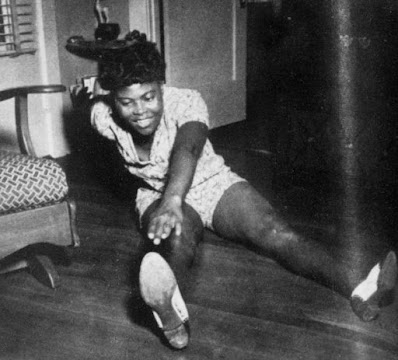

Mabel Fairbanks was born on November 14, 1915 on the land of the Seminole people in the Florida Everglades. She didn't know her father and her mother died at the age of eight, after which she was raised by her grandmother in Jacksonville. At the age of fourteen, she was sent up to New York City to live with her sister and take a business course. While working as a babysitter to a young mother, she watched other people her age skating on a small pond that wasn't far from Central Park and was so taken by the sport that she became determined to take it up herself.

Using a dollar and twenty five cents from her meagre babysitting wages, Mabel bought a pair of used skates at a pawn shop that were two sizes two big and stuffed them so they'd fit, and headed out skating on the pond. She struggled with the subpar ice conditions and an onlooker suggested that she'd fare better at an actual rink. To say Mabel, who was of both African American and Seminole heritage, wasn't exactly accepted with open arms was the understatement of the century. A cashier at the Gay Blades Ice Casino on Broadway and 52nd Street told her "blacks didn't skate there". She returned several time and each time was told th same thing and turned away. Finally, Lewis Clark (a manager at the rink) let her take to the ice. Maribel Vinson Owen and Howard Nicholson were sympathetic and offered her some tips, but she certainly wasn't welcomed to the sport with open arms.

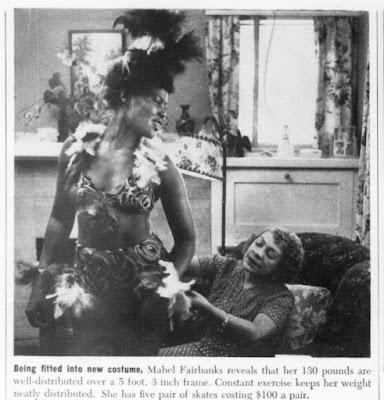

Photo courtesy "Ebony" magazine

I want to get a few things across here. This wasn't the bible belt; this wasn't Alabama, Tennessee or Arkansas. This was New York City and the racism wasn't watered down in the least. Maribel Vinson Owen and Howard Nicholson weren't permitted to teach Mabel on the regular sessions, so they stayed behind and gave her free lessons on the public sessions because she saw something in her. When you have rinks blatantly posting signs that say "No Negroes Allowed", not only was Mabel at risk of being booted out of there at any minute, Maribel and Howard were in real danger of losing her jobs and/or students for helping Mabel... and that's a big part of this story that's not given much contemplation. Also, Mabel just wasn't a good skater, she was an excellent skater. Yet, she couldn't test or compete. Want someone to point your finger at? Look no further than the two men who held the presidency of U.S. Figure Skating from 1930 to 1937 in alternating terms: eight-time U.S. Champion Sherwin Badger and former pairs skater Charlie Morgan Rotch. They called the shots at the time. They could have changed things if they wanted to, but they didn't. This isn't really about finger pointing though, because right down to the cashier who wouldn't let Mabel in to skate to the parents and fellow skaters who viewed her with derision, racism was and is a societal problem... not just an issue of a couple jerks being jerks.

Photo courtesy "Opportunity" magazine

At any rate, the ever-determined Mabel didn't give up hope of being able to compete with her peers and even tried to do something about it. In the "LA Times" in 1998, she recalled, "I wanted to train for the Olympics. So I went to black doctors, lawyers, teachers, anyone I could think of who might help fund lessons and everything I'd need. They all said, 'Go away little girl.'" By now most people would have hung up their skates but Mabel wasn't having it one bit.

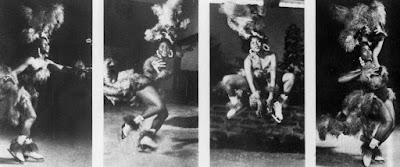

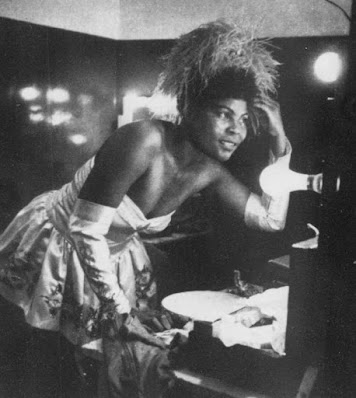

In 1940, Mabel ultimately made the decision to leave New York City behind and move to California. With the help of a promoter named Wally Hunter, she embarked on a professional career, performing with Belita in "Rhapsody On Ice" at the Teatro Blanquita in Havana, in USO nightclub shows in France and Germany, "School Days On Ice", George Arnold's Ice Revue in Palm Springs and on an ice tanks installed at the historic Apollo Theater in Harlem and the Gayety Theatre and Play Room Night Club in Los Angeles. She also performed as a dancer in a floor show called "Harlem Holidays" at the Little Harlem Club in Los Angeles, wowing audiences with a dance she called the 'Holly-Harlem-Hula-Boogie'. She'd received instruction in dance from Jean Hamilton of Michael's School of Acrobatics.

Bob Turk and Mabel Fairbanks. Photo courtesy "Ebony" magazine.

A clip of Mabel's skating found its way to the "All-American News" - America's first newsreel catering to black audiences - in 1945. Her skating took her to places of the world many only dreamed of visiting, but when she wanted to be considered for the big touring ice shows of the time - the Ice Capades and Follies, she was flatly turned down and told, "We don't have Negroes in ice shows." A letter to Sonja Henie, whom she'd idolized after seeing "One In A Million", went unanswered.

Photo courtesy "JET" Magazine

World Champion Randy Gardner explained, "Mabel's professional skating career was during the time where there was segregation in this country and abroad. I remember her telling me that when she would do shows, during the breaks or at dinner time, she would have to sit outside away from the other cast members to eat her meal. But, Bob Turk (who later became producer and director of the Ice Capades) would go out and sit with her during those times so she wouldn't have to be alone. Even going through those experiences, she had so much spirit and drive, I guess she had to create a survival technique in order to succeed in a prejudiced world. And she did!"

Photos courtesy "Ebony" magazine (top) and "JET" magazine (bottom)

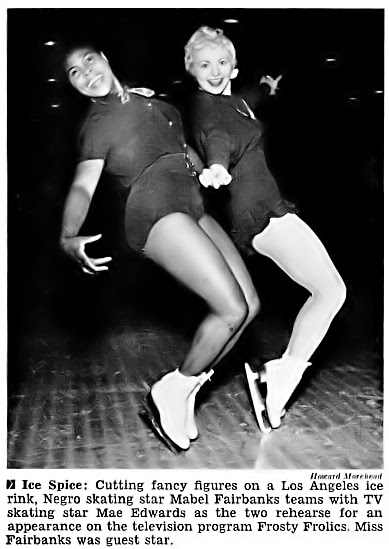

Ignoring the signs of "coloured trade not solicited" displayed in California rinks, she embarked on a lucrative coaching career in California at The Polar Palace in 1949. She continued to perform professionally throughout the fifties and early sixties, appearing in the television program "Frosty Frolics" and the International Ice Festival in Bogota, Colombia.

Mabel also toured with her own show, "Ice America", which was billed as the "world's only interracial ice and stage show". The tour donated a portion of the proceeds to the Bronx charity Eastside Settlement House Building Fund.

In 1951, Mabel toured the Southern states in George Arnold's production "Rhythm On Ice" and was sent by Columbia Pictures to the Far East, where she was the only American star in a skating production at a Japanese rink.

Photo courtesy "Ebony" magazine

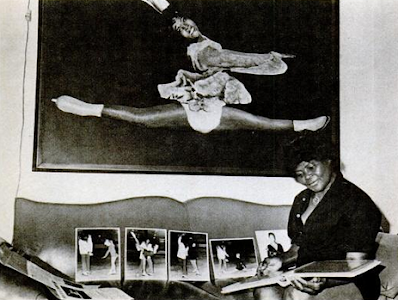

Over the years at the Polar Palace and Iceland, Mabel taught a who's who of Hollywood how to skate - Natalie Cole, Eartha Kitt and her daughter Kit, Joe Louis, Dean Martin's whole family, Danny Kaye and Bing Crosby's granddaughter among them. She also coached an impressive roster of elite competitive skaters and mentored skaters like Debi Thomas, Kristi Yamaguchi, Rudy Galindo and Scott Hamilton. If someone was too poor to pay for lessons, she taught them for free and let them stay with her at her home on Laurel Canyon Boulevard... that's what kind of woman Mabel was. She continued to fight for the rights of skaters of colour her whole life, petitioning the Culver City Skating Club to admit Richard Ewell III to its membership in 1965, making him one of the first African American skaters to gain admission to a U.S. figure skating club. The next year, she coached Atoy Wilson to become America's first U.S. champion of colour when he won the novice title at the 1966 U.S. Championships. She coached Ewell and his partner Michelle McCladdie, who become America's first African American pair team to win a U.S. junior title in 1972. When Rory Flack wanted to quit skating at the age of thirteen because of the racism she was experiencing, Mabel urged her to soldier on.

Left: Tai Babilonia and Mabel Fairbanks. Right: Mabel Fairbanks and her student Gjert Gjertson standing in the ruins of The Polar Palace, destroyed by fire in 1962

Mabel was also the person who paired World Champions Tai Babilonia and Randy Gardner. Tai recalled, "Mabel was not of this planet. She was unique, eclectic, one of a kind, motivating. I could go on and on. In the late sixties, in her locker in the back room at the rink in Culver City, she had at least four pairs of skates in different colours. I think they were Harlick's made especially for her? I never asked. A pair were pink and that's why I wear the pink skates - to honor her. She had flaming red hair, her wardrobe was different and eclectic. It looked part couture, part old pieces she had... just a mix and match of everything. It's so hard to explain her but she really liked to stand out and she knew how. She lived in Hollywood and the house is still there. For a lot of her students it was like our second home. We'd stay there after skating Friday nights and have sleepovers and she'd drive us to the rink the next day. I have magical memories of that home. She lived a block and a half north of Sunset Boulevard. It was just so normal for us. On ice, she was very much a disciplinarian but just so motivating!"

Photo courtesy "Ebony" magazine

Randy Gardner recalled, "I started group classes with Mabel when I was seven years old. She was exuberant, colourful and fancy. I had never really met anyone quite like that before. Her personality made her classes and private lessons so much fun. I couldn't wait to get to the rink to take her class. Mabel was the one that paired up Tai and me for the local skating club show. She took a chance, I guess, but she really encouraged us to skate pairs, but neither of us really wanted to do it. After all, I was ten years old and Tai was eight. Later in life, when she had retired and health issues arose, she never forgot to call me during all the holidays, especially Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Years. Those calls made me feel like I was special, just like she always had when I was young boy beginning to skate... She changed my life, my family's life, she changed Randy's life. Who knew it would start with something as simple as 'hold his hand and skate around the rink together'... To say that we are still holding hands so many years later, that's so powerful to me. I am so grateful for the lessons from her that I learned that I still use in my skating life and everyday life and as a mother, person and a woman. She never backed down and that's what I loved about her. You don't back down. You learn from that. She fought for herself but more than that she fought for us. She was a remarkable woman."

Photo courtesy "Ebony" magazine

Mabel devoted the majority of her time to skating, but also enjoyed swimming, playing tennis, exercising, glass etching and painting. She never really got into dating, telling an "Ebony" reporter, "Skating was my great love. Everyone wanted to marry me, but I was married to skating." Her students became almost like surrogate children to her and she coached until she was seventy nine years old.

At the 1997 U.S. Figure Skating Championships in Nashville, Mabel was inducted into the U.S. Figure Skating Hall Of Fame, a moment that meant just so much to her and the students lives that she touched. Tai Babilonia recalled, "That was her moment! I was there and Atoy [Wilson] was there. I've never seen her happier than that night. Mabel getting that induction and to be there for her and walk her out on the ice, that is up there in the top three moments of our career, because without that, we wouldn't even be talking."

Photo courtesy "The Greater Omaha Guide"

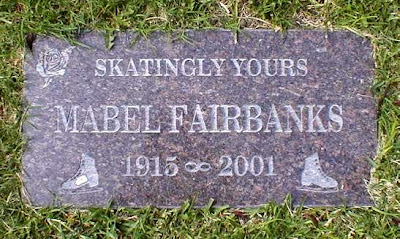

Sadly, Mabel was diagnosed with the neuromuscular disease Myasthenia gravis in 1997. In 2001, she was also diagnosed with leukemia. She passed away in Burbank, California on September 29, 2001, the same month as the 9/11 attacks in the city she grew up as a young skater. Tai Babilonia kept in touch with Mabel until the day she passed. She received a call from Atoy Wilson letting her know that Mabel had just passed away and rushed to the hospital right away to sit with her. "I felt she was still there," Tai recalled. "To be able to sit and have that final conversation... that was a very special moment."

In 1998, when a reporter visited Mabel's home and teared up hearing about the struggles she faced in the figure skating world, Mabel told her, "Don't cry dear... I've cried enough for all of us." Thank you, Mabel Fairbanks, for making an impact... and for never backing down.

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.