As culture shifted in the world's great cultural centers like London, Paris, New York City, Berlin and Los Angeles with the advent of a new era following the drudgery and strife of World War I, economies around the world boomed and flapper dresses, the Charleston and art deco were all the rage. Canadian figure skating enjoyed that same surge in popularity following World War I. After a four year span where the Canadian Figure Skating Championships were not held from 1915 to 1919, they returned in 1920 with a flourish.

|

| Jeanne Chevalier and Norman Scott |

Canadian men's skating during the 1920's would be dominated by Melville Rogers, who won five Canadian titles from 1923 to 1928 and also (like many skaters of the era) competed in multiple disciplines. Rogers found success on the international stage as well, earning his rightful place in the history book as first male singles and pairs skater from Canada ever to compete at the Winter Olympics in 1924 at the Chamonix Games. Rogers also won two North American men's titles and three North American fours titles and went on to serve as the Canadian Figure Skating Association's President for two terms following his retirement from competitive figure skating in 1937.

A rare glimpse at the 1924 Winter Olympics in Chamonix from Frazer Ormondroyd (no footage of these wonderful Canadian skaters, unfortunately but gives you a wonderful glimpse into skating during that era)

Rogers' pairs partner at the 1924 Winter Olympic Games in Chamonix was none other than the same lady who would represent Canada in the ladies event (becoming the first Canadian ladies to compete at a Winter Games) Cecil Smith. David Young's book "The Golden Age Of Canadian Figure Skating" noted that Rogers and Smith were not originally intended to be Canada's sole representatives at those historic first Olympics for Canadian figure skating. Young explained that "originally, former Canadian champion Duncan Hodgson of the Montreal Winter Club, and the reigning ladies' champion, Dorothy Jenkins of the Minto Club, Ottawa, were selected to go as well. Marjorie Annable of the Winter Club, and John Machado of the Minto Club, were back-up skaters in case any of the original four had to drop out. In the end, however, only the Toronto pair travelled to France, as the others withdrew. 'They had no opportunity to practice,' was the reason. 'There has been no ice at Montreal or Ottawa, whereas Toronto has an artificial plant at the Dupont Street Rink.'" With most events still being held outside domestically in those days, it seems so funny but foreign to us today that a mild winter could be the reason for a skater's Olympic dreams being dashed. Cecil Smith, who competed mainly against Constance Wilson for much of her career, became a very popular and respected skater through her career. An account of Cecil's first Canadian title win (where she unseated Wilson) in Young's book reads: "Both did splendidly in the school figures... and their free skating performances were equally artistic and were both skated with the acme of grace and proficiency. Some favoured Miss Smith... for the delicate lightness of steps throughout, her airy leaps and her beautiful spins; others thought that Miss Wilson was a shade more finished and that in evenness and confidence of execution she had a slight advantage..." Smith again defeated Wilson in 1926 (winning both the figures and free skating) and would go on to become the first Canadian skater to win a World medal at the 1930 World Figure Skating Championships when she won the silver just behind Sonja Henie. An account of her medal winning performance from Young's book reads: "Miss Smith, who in her school figures had shown a subdued grace that won her the esteem of the critics... made her bow with a long swan glide, ending with a one foot spiral, and then set off to dance in complete abandon. Afterwards, the beautiful Canadian girl declared that she was startled for a moment as she looked up at the crowded galleries. Then, as the crowd, sensing her wonderful grace and poise began cheering, she set forth to outdo herself. Her performance was received by loud applause." Not to be outdone, Wilson would win a World medal of her own in 1932.

Although Smith (who won her first international medal in 1924 in Manchester, England) won two Canadian ladies titles, she would not win a Canadian pairs title like her Olympic pairs partner Rogers (who claimed the title in 1925 with Gladys Rogers). Wilson would win the 1926 Canadian pairs title with Errol Morson and then win a handful of titles in the late twenties and early thirties with her older brother Montgomery Wilson, who won the 1932 Olympic bronze medal. Constance Wilson's successes were in their own right remarkable - an account in Young's book describes the student of Mr. Gustave Lussi as "Pavlova in her prime, but Pavlova with winged feet and light as a fawn..." - and her fourth place finish at the 1932 Games remains to this day of one few top finishes by Canadian ladies skaters in an Olympic event, including her in a small but prestigious club amongst the likes of Barbara Ann Scott, Liz Manley and Joannie Rochette.

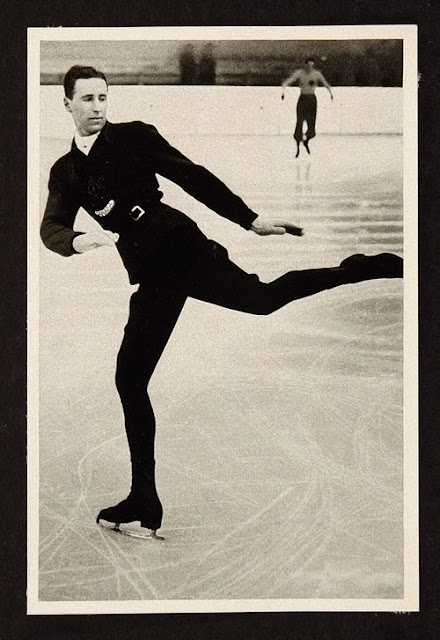

|

| Montgomery Wilson |

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of the figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.